On April 28, 1945, a portion of the American forces set off on an incredibly dangerous and unique mission. Dubbed Operation Cowboy, it saw them team up with German and Cossack soldiers to save the world’s most valuable horses from the encroaching Red Army. In turn, they saved an equestrian bloodline that is over 400 years old.

The value of Lipizzaner horses

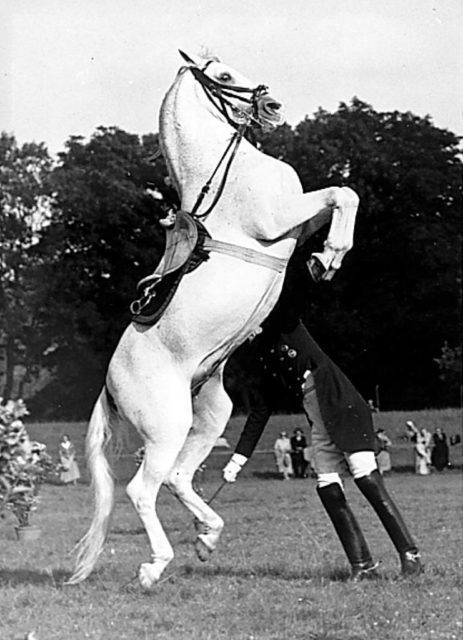

The beautiful, white Lipizzaner horse’s lineage dates back to the 16th century, and its name comes from the location of a stud farm set up by Habsburg Archduke Charles II Francis. A cross between the Arabic and Iberian breeds, it became one of the most priceless horses in the world.

In World War I, the horses were relocated to Austria for safety reasons. They found themselves in a similar position during the Second World War and were relocated to Czechoslovakia. It was there that the Lipizzaner bloodline nearly came to an end.

“Aryan” horses

As early as 1938, when the Lipizzaners were confiscated from the Spanish Riding School in Vienna, the German government had a plan to create an “Aryan” horse breed. They placed just as much value on the Lipizzaner’s lineage as the rest of the world, and aimed to create the perfect military horse.

In April 1945, Luftwaffe intelligence officer Col. Walter Holters was stranded at the Lipizzaner stud farm, which was close to being taken over by the Red Army. A horseman himself, Holters was sure that the Lipizzaners were doomed if the Russians reached the farm, as they’d previously shot a number of horses within the Royal Hungarian Lipizzaner Collection to death.

To save the horses, Holters sought the help of the American forces – in particular, the 42nd Cavalry Reconnaissance Squadron, 2nd Cavalry Group, which was part of Gen. George Patton‘s XII Corps.

Col. Holters secretly plans his next move

Holters befriended fellow horseman and German Lt. Col. Hubert Rudofsky while he and his troops were stranded in Hostau, where the stud farm was located. He was in charge of the farm and Holters hoped to convince him that cooperating with the Americans was necessary. Unfortunately, Rudofsky wasn’t willing to surrender to save the horses; he didn’t want to betray his German loyalties.

This didn’t matter, as Holters secretly took the situation into his own hands. He approached the 42nd Cavalry Reconnaissance Squadron, 2nd Cavalry Group, XII Corps of Patton’s Third Army and promised the Germans would surrender if the Americans helped move the Lipizzaner horses to safety.

Patton gave the go ahead and Operation Cowboy was soon underway.

The German defenses stationed between the stud farm and the Americans were not aware of the plan and needed to be defeated to establish a path to and from the area. A small task force of men, consisting of two cavalry reconnaissance troops with M8 scout cars, five small M24 Chaffee light tanks, a pair of M8 Howitzer Motor Carriages and around 325 infantrymen, was originally provided for the mission. Tasked with commanding the group was Maj. Robert P. Andrews.

Given they were already exhausted after nine months of battle, the 20-mile trek to the farm would be exhausting and difficult.

Capt. Thomas Stewart’s “Foreign Legion”

When the task force was passed off to Capt. Thomas Stewart, it had been reduced to just two tanks, one cavalry troop and the M8 Howitzer Motor Carriages – 180 men, in total. He needed to seek out additional help and turned to the Allied prisoners of war who worked on the farm and were released following the German surrender.

Stewart was also able to get some Russian Cossacks, who’d joined the Axis following the German invasion of the USSR, to help fight the German forces. The Cossacks were terrified of the Red Army and wanted to get the horses to safety.

This ragtag force of men were dubbed Stewart’s “Foreign Legion.”

Operation Cowboy

On the way out of Hostau, Stewart’s men were able to hold off troops of the Waffen-SS. Had the Germans been equipped with tanks, the outcome would have been a lot different. The “Foreign Legion” held off the first round of soldiers, and during a lull in the fighting were able to move the horses across the battlefield.

The majority of the Lipizzaners were ridden by American, German and Cossack officers, but some required more delicate transportation, as they were either pregnant or had recently given birth. Those that couldn’t be ridden were rounded up Wild West style and herded to safety or packed into makeshift transportation vehicles and sent out west.

More from us: George Patton bought supplies from Sears because the US was so unprepared for WWII

The troops were able to move the around 500 Lipizzaners to safety without a moment to spare, as word came that Soviet T-34 tanks had just arrived in the eastern-most part of the city. Ultimately, the horses were brought to safety and Operation Cowboy was deemed a success.