Some myths about military history are too good to be true. However, with the best ones, once you peel back the myth, you find a real story that’s just as fascinating. That’s the case for Geoffrey Tandy, the British seaweed specialist who helped win the Second World War.

The Myth of Geoffrey Tandy

Geoffrey Tandy rose to fame not in his own lifetime, but in the internet age.

The story shared on social media is a compelling one. Tandy had been an academic working at the British Museum. A botanist who primarily studied sea life, he specialized in algae, fungi, and lichens, a group collectively known as cryptograms. He was a quiet, unassuming scholar, one of those curious obsessives who once filled British academia.

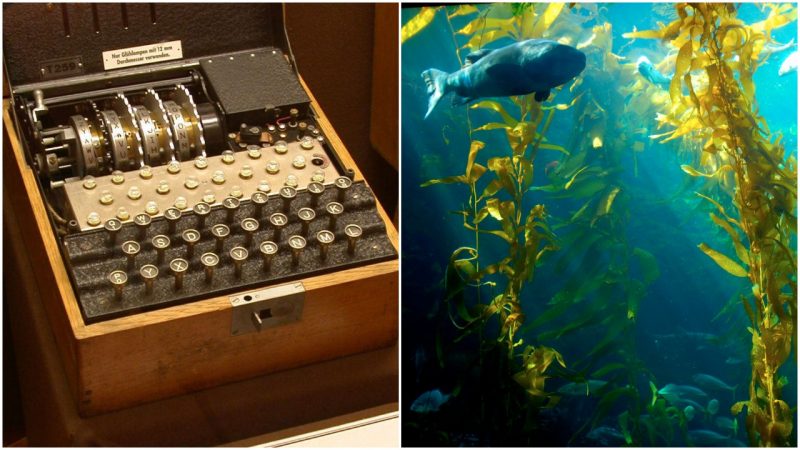

Then came the Second World War. The British military was desperate for specialists who could break Axis codes, particularly the German Enigma cipher. Confusing the titles “cryptogamist” and “cryptographer”, they assumed that Tandy was a code man.

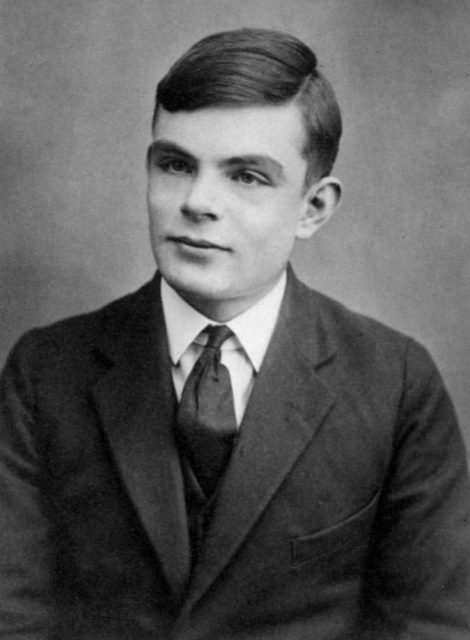

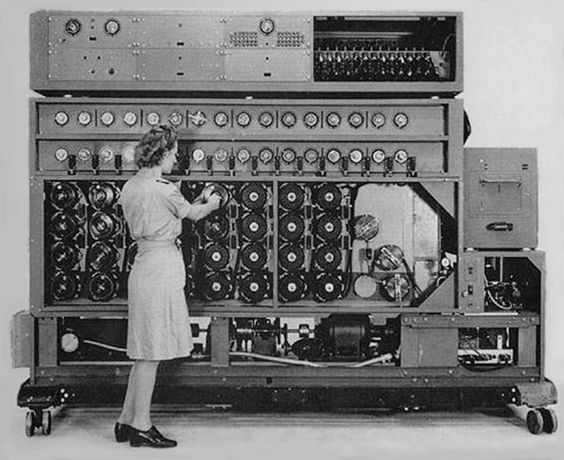

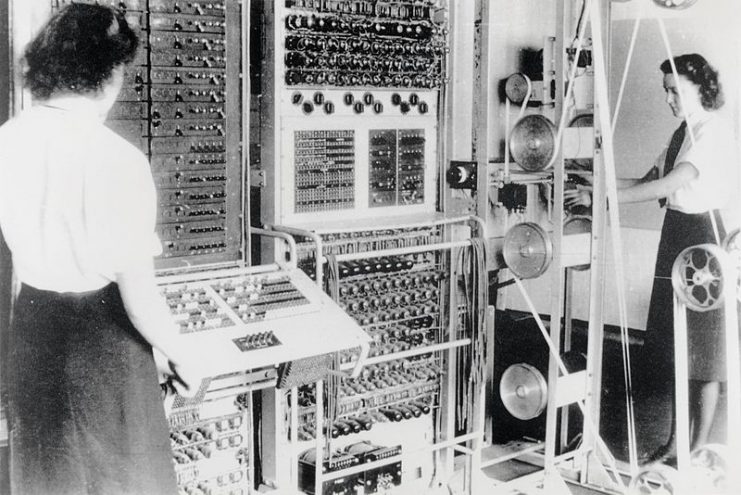

Tandy was recruited to the legendary collection of code-cracking experts at Bletchley Park, the workplace of the likes of Alan Turing. Only when he got there did anyone realize the mistake. Given the secrecy around Bletchley Park, they decided that it was best to keep Tandy there.

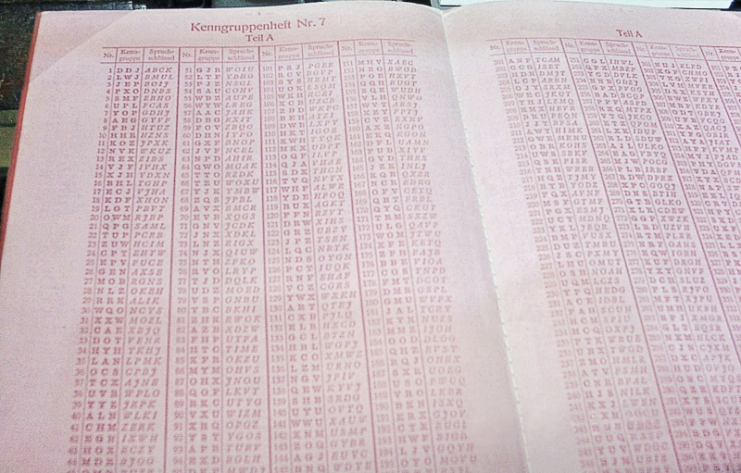

For years, he struggled to get to grips with his new line of work, contributing little to the effort. Then came the day when codebooks captured from a German U-boat, soaked during its sinking, were brought to Bletchley.

Everybody else feared that they would be unusable, but Tandy applied his expertise in preserving damp samples, learned while studying sea life. He made the sodden pages readable, and in so doing helped crack the Enigma code.

It’s a fantastic story, and it’s easy to see why it caught people’s imaginations. But it isn’t true. Fortunately, the real story is just as fascinating.

A Scholar and a Veteran

The real Tandy’s military career began in the late days of the First World War when he served in the Royal Field Artillery. After the war, he completed a degree in forestry at Oxford University, one of the most prestigious educational institutions in the world. In 1926, he became an assistant keeper of botany at the British Museum.

In this role, Tandy’s job was primarily to keep records, acting as something like a librarian. He developed skills in handling and preserving fragile documents, as well as picking up various languages and technical jargon. He wasn’t much of an academic and only had a few articles published.

Building British Intelligence

Between the world wars, Britain, like many countries, neglected the field of military intelligence. It was only during the late 1930s that Admiral James of the Royal Navy, recognizing the storm clouds growing over Europe, began building up the Navy’s military intelligence department.

During the First World War, James had been part of Room 40, the team decrypting German signals, and so he recognized how important intelligence work could be. He worked to build up the tiny and neglected Naval Intelligence Division. Despite his efforts, by 1939 it only had 50 staff members.

When the Second World War broke out, intelligence work went into overdrive. There was a sudden and desperate need to better understand what the Axis powers were capable of and what they were doing.

There were no specialist training schools from which the needed intelligence analysts could be recruited, and so other criteria had to be used. The barrister Ewen Montagu and author Ian Fleming were just two examples of men suddenly brought into a very different career.

However, there were plenty of criteria that could be used to identify suitable candidates. A good education was clearly necessary. Proven experience in analytical work of some kind, and some military experience, to better understand the information coming in and how it would be used, would be useful, too.

This made Tandy a perfect fit, and so he was recruited to work at the fast-growing intelligence station at Bletchley Park. This wasn’t an accident brought about by mixing up long words. It was a reflection of Tandy’s skills and experience.

Rather than being a figure on the sidelines who was unable to understand the work being done, Tandy was the leader of NS VI, a bureau that specialized in interpreting the technical language of foreign naval documents.

The team was full of experts in languages and library work, just like Tandy. When other teams came across a piece of jargon or an abbreviation that they couldn’t understand, the NS VI would set to work identifying its meaning and providing the closest equivalent in English.

Geoffrey Tandy wasn’t at Bletchley Park by accident. But the presence of a seaweed specialist opens a window onto the extraordinary nature of the facility, with experts from hundreds of different fields coming together to invent the modern art of deciphering.

Tandy and Enigma

So why the myth about Tandy?

The mixing up of the words cryptogamist and cryptographer may have started as a joke among the staff at Bletchley Park. It fits perfectly with the British sense of humor, where people are expected to belittle their own achievements and attribute any success to chance.

The idea of mixing up two obscure specialties, and in the process making a government official look foolish, would have been the perfect in-joke for a group of language and mathematics experts. It was only later that people began to believe the story, and thereby creating Tandy’s legend.

So did Tandy really salvage a set of water-sodden codebooks? He certainly could have done – after all, he had the skills in preserving fragile documents. However, the story is such a perfect fit for the legend that it could easily have been invented as part of the joke.

In the end, though, it doesn’t really matter. Whether he was translating obscure documents or preserving damaged pages of secret code, Tandy was doing the same as all the Bletchley Park staff – applying his expert knowledge to achieve extraordinary insights and so help win the war.

Sources:

Ralph Bennett (1999), Behind the Battle: Intelligence in the War with Germany 1939-1945.