On April 1, 1941, a group of specially chosen members of the Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN) attended a secret meeting, where they were told, “You are going to receive a very special type of training… In a secret weapon.” Eight months later, 10 of those men and their five mini submarines participated in an event that would drastically effect the course of World War II: the attack on Pearl Harbor.

Japanese military officials had decided to execute a surprise attack against the US Pacific Fleet, hoping to cripple or destroy it before the country declared war. To accomplish this, they planned a massive air assault and, almost as an afterthought, a mini submarine attack. They expected the submersibles to sneak into the harbor and aid the air attack, but the mission failed.

Japan’s top secret new weapon

When Japanese military officials considered war with the United States, they believed full-sized submarines would be too slow and their firepower too limited to be useful in a long-range conflict. The development of the Type A Kō-hyōteki-class opened up new possibilities.

The first two mini submarines were built in 1934 under the name, “Metal Fitting, Type A,” and successfully tested as “A-targets” to maintain secrecy. Production increased in the following years, with components made in a private shipyard and transported to an isolated island for assembly.

In the summer of 1941, 24 specifically-selected submariners began training at a remote base where security was so tight the few inhabitants weren’t permitted to own cameras. The Japanese concealed the mini submarine program so successfully that many in the IJN remained under the impression the tube-shaped objects were gunnery targets.

Approximately 78 feet long by six feet wide and powered by an electric motor, each streamlined submarine required only two operators. Their firepower consisted of two torpedoes, each 18 inches in diameter and containing half a ton of explosives. According to Masataka Chihaya, an aide to Adm. Isoroku Yamamoto, the vessels were intended for use in decisive battles on the high seas, where speed would be paramount.

Despite this, officials decided to incorporate five into the Pearl Harbor attack plans. They knew it would be impossible for a full-sized submarine to enter the waters around Ford Island undetected, but perhaps the mini ones could manage the difficult task.

The attack on Pearl Harbor would be a massive undertaking

Japanese spies had reported that the interior of Pearl Harbor couldn’t be viewed from the outside. Even in daylight, the entrance could only be seen from within several miles of it. At night, the mini submarines would have to surface within that zone and use their periscopes to get a navigational fix on landmarks.

To further complicate this aspect of the mission, the Americans had designated the area outside of Pearl Harbor as a Defensive Sea Area. As such, the Japanese could only speculate whether additional obstacles lay along the route. If one submarine evaded patrols and reached the mouth of the harbor, the vessel still had to slip into the narrow entrance, navigate a coral-lined channel clouded by silt and find a place to hide beneath the shallow waters.

Considering the odds, Vice Adm. Ryūnosuke Kusaka later meditated, “Surely even the slightest chance of survival could hardly be seen in their assigned mission.” Why, then, were the mini submarines included in the attack plans for Pearl Harbor?

Adm. Yamamoto, commander-in-chief of the Combined Fleet, gave the idea his tentative approval because other officials believed a submarine attack would enhance the cumulative damage of the air assault on Pearl Harbor. Rear Adm. Hisashi Mito later noted in an interview that the vessels were also considered “double insurance,” in case the air attack failed.

Adm. Chūichi Nagumo, commander of the Pearl Harbor task force, and Mitsuo Fuchida, who led the pilots, disagreed. They were certain the submarines would give away the surprise by either taking premature action or being spotted before the attack.

Many disapproved of the mini submarines’ use

The Japanese modified five I-class submarines from Capt. Hanku Sasaki’s First Submarine Division, so each “mother” could carry a mini submersible piggy-back style, strapped to her deck, behind the conning tower. Sasaki was given little notice as to what was going on, but, once he found out, he immediately joined Nagumo and Fuchida in their disapproval of the idea.

Sasaki felt it unwise to make hasty changes to equipment and put it to use without taking the time to fully test it. In fact, the first trial run of a mother submarine carrying a mini one resulted in damage to the latter, hardly promising.

Up until mid-November 1941, the mini submarines’ inclusion in the attack on Pearl Harbor was tentative, and the water-based attack plan changed several times. At last, the orders were finalized. They were to enter the harbor at night, hide until the attack began, and then launch a strike between the first and second aircraft waves. They would circle counterclockwise around Ford Island, torpedo a battleship or aircraft carrier along the way, and quickly make their escape.

Since the mother submarines would be free to operate on their own after releasing the mini vessels, their role was to lie in wait outside of the harbor and torpedo any ships that came out. After the mission was complete, they would collect the minis at a rendezvous point near Lanai.

None of the mini submariners chosen to participate in the attack on Pearl Harbor expected to reach Lanai. From the beginning, they’d told Vice Adm. Mitsumi Shimizu, commander-in-chief of the Japanese submarine forces, that “maximum damage to the enemy is what counts, not our survival.”

Launching the attack on Pearl Harbor

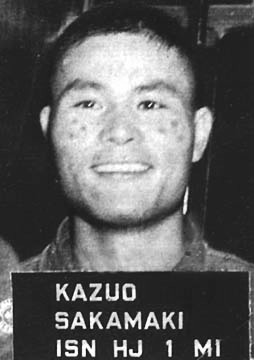

At last, the hour for departure arrived. The first mini submarine left her mother submersible around 1:00 AM on December 7, 1941, with the others following at intervals until 3:33 AM. HA. 19, manned by Kazuo Sakamaki and Warrant Officer Kiyoshi Inagaki, launched with a broken gyrocompass. Inagaki’s attempts to repair the piece the previous day had been unsuccessful.

Sakamaki stood firm in his intention to carry on. The air strike was scheduled to begin shortly before 8:00 AM, but dawn would come two hours earlier, giving the mini submarines only a few hours to reach Pearl Harbor.

The mini submarines are sighted

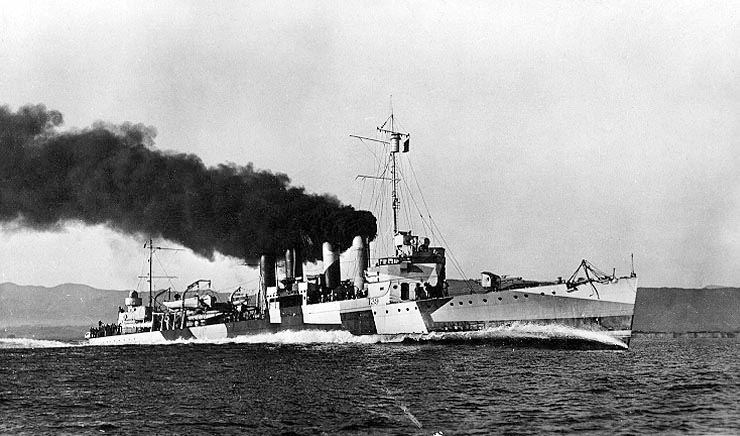

Despite the cover of darkness, the Americans detected two of the mini submarines before they reached the entrance to Pearl Harbor. Ensign R.C. McCloy, the officer of the deck on the minesweeper USS Condor (AMc-14), spotted the first at 3:42 AM, after noticing something splashing through the water. The ship’s quartermaster identified the strange object, saying, “That’s a periscope, sir, and there aren’t supposed to be any subs in that area.”

Condor used her signal blinker to inform the USS Ward (DD-139), the destroyer on duty in the Defensive Sea Area, that she’d seen a submarine. Lt. William Outerbridge, who had taken command of Ward only two days prior, immediately sounded General Quarters. The destroyer searched the area for over half an hour, but found nothing. Outerbridge figured that, since Condor didn’t report the sighting, the minesweeper’s crew mustn’t have been positive it was a submarine.

The second mini submersible was seen at about 6:30 AM, when Cmdr. Lawrence Grannis of the supply ship USS Antares (AKS-3) noticed a suspicious object following his vessel toward the harbor’s entrance. He promptly radioed Ward. The message was taken by Ensign O.W. Goepner, who figured the object was just a buoy.

Despite his suspicions it was nothing to worry about, Goepner told Antares‘ quartermaster to “keep an eye on it.” After watching the object for awhile, he concluded, “Sir, it looks like a small conning tower, and I’ve never seen a buoy move at five knots through the water.”

They woke up Outerbridge, who came on deck, looked at the object and immediately thought, “She is going to follow the Antares in, whatever it is.” Convinced the object “couldn’t be anything else” but a submarine, Outerbridge fell back on his orders to fire on unidentified, unescorted vessels trespassing in the Defensive Sea Area.

General Quarters sounded for the second time that morning, and Ward‘s sailors manned their battle stations. This time, they got some definite action.

One mini submarine is taken out

The mini submarine apparently never saw the destroyer coming, and the USS Ward was only 50 yards away when her first shot went over the conning tower and splashed into the sea. The second solidly hit the part. As the submersible slowed and began to sink, Ward attacked with depth charges.

Outerbridge sent two messages to headquarters. Thinking the first might be interpreted as a false alarm, he elaborated in the second, saying, “We have attacked, fired upon, and dropped depth charges upon a submarine operating in defensive sea areas.” Shortly after, Ward depth-charged another contact, though without conclusive results.

Upon receiving Ward‘s radio messages sometime after 7:00 AM, the commanders at Pearl Harbor were taken aback. They began to take routine measures to counter the submarine threat, such as ordering the USS Monaghan (DD-354), the ready-duty destroyer within the harbor, to join Ward. After much discussion, they decided to “obtain a verification” of Ward‘s report before taking further action.

They were still waiting when the Japanese air strike began. Fortunately for the enemy pilots, the Americans had failed to realize the submarine was an advance notice of an impending larger attack. However, she did serve as a warning that other vessels were lurking outside of the harbor, so the mother submersibles lost the chance for their own surprise assault.

Only one mini submarine managed to enter Pearl Harbor

Only one mini submarine is certain to have actually entered Pearl Harbor. Despite reaching her destination, she failed to aid the air strike by sinking any ships – instead, she was chased down and destroyed. The tugboat YT-153 spotted the vessel’s periscope and tried to run her over, but the submarine disappeared into cloudy water. Shortly thereafter, at 8:39 AM, the seaplane tender USS Curtiss (AV-4) hoisted a signal flag to indicate that a submarine was inside the harbor.

“Curtiss must be crazy,” stated Cmdr. William Burford of the USS Monaghan, which was underway to join the USS Ward. However, after his signalman pointed out what looked like “an over and under shotgun barrel looking up” at him, Burford declared, “I don’t know what the hell it is, but it shouldn’t be there.”

As Monaghan began to charge the submarine, intent on ramming the vessel, Curtiss scored a direct hit on the conning tower, decapitating her captain. In a post-war interview with historian Gordon Prange, Burford described the standoff. One can imagine the chaos: the speeding ship, swarming aircraft, falling ordnance, explosions, billowing smoke, anti aircraft fire and a restricted maneuvering space. Burford concluded, “God – a lot was going on in just a few minutes of time.”

The mini submarine, meanwhile, had contributed to the general mayhem by firing both of her torpedoes, but missing her targets. The first hit a dock, instead of Curtiss, while the second missed the oncoming Monaghan by 20 yards and exploded on the bank of Ford Island. Failing to directly ram the vessel, Monaghan depth-charged her, totally destroying the submarine at the danger of blowing off her own stern.

Meanwhile, outside of the harbor…

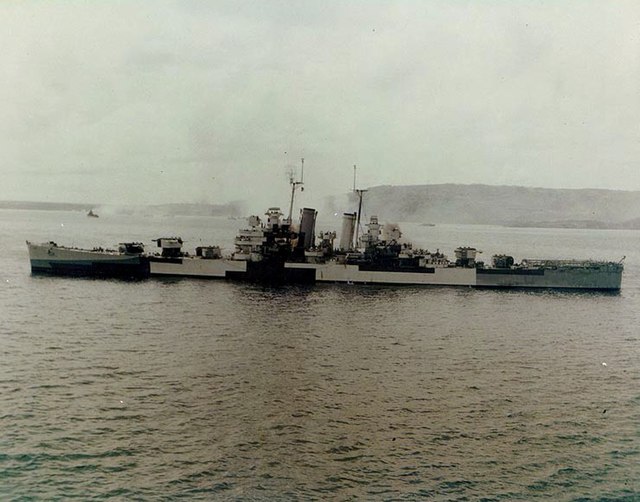

American contact with Japanese mini submarines outside of Pearl Harbor continued throughout the air attack, but none succeeded in preventing any ships from leaving, nor did they sink any on the open sea. The closest call came against the light cruiser USS St. Louis (CL-49), the only large ship to leave the harbor during the attack.

As St. Louis proceeded down the channel at 10:04 AM, Capt. George Arthur Rood saw two torpedoes coming directly toward them. Through some zig-zagging in the narrow channel, St. Louis managed to dodge them, and the torpedoes exploded on a nearby coral reef. Having just lost (literally) a ton of weight, the mini submarine bobbed to the surface. The sailors on St. Louis fired, believing they’d hit the conning tower. However, the vessel submerged, and they weren’t positive it was an official kill.

As the second wave of attacking aircraft receded, the situation outside of Pearl Harbor got livelier for any submarines unwary enough to come within reach of the vigilantly patroling destroyers. At 9:26 AM, American military officials ordered, “Send all destroyers to sea and destroy enemy submarines.”

The destroyers spent the day submarine hunting, blasting anything that seemed to be a contact. Some ran out of depth charges and had to return to Pearl Harbor for more. If the third submarine had survived any encounters with American ships earlier in the morning, she was likely damaged or sunk by this point.

The fourth is accounted for until 12:41 AM on December 8, when Ensign Masaharu Yokoyama radioed, “Successful surprise attack” to I-16. He was never heard from again.

HA. 19‘s day of futility

In the midst of all the action, one mini submarine hadn’t accomplished anything: HA. 19. Taken all together, the details of Sakamaki’s efforts during the attack on Pearl Harbor read like a disastrous clash between a grim determination of will and Murphy’s Law. After the war, he recorded his account of the mission in a memoir, titled I Attacked Pearl Harbor.

When I-24 released her mini submarine in the pre-dawn darkness, HA. 19 “nearly toppled over into the water” and started to sink nose-first. After Sakamaki and Inagaki shifted enough ballast to right the vessek, they set out for the harbor. After several hours of navigating in circles, Sakamaki dared to surface to investigate. Morning had come, and he reported to Inagaki that “just a couple of destroyers” were on patrol, right before he “heard an enormous noise and felt the ship shaking.”

After the two men recovered from the shock of what must have been a depth charge, their submarine floundered around some more, but to no avail. Sakamaki claimed he could have sunk a destroyer “as easy as killing a bird in the palm,” but that he preferred to save his torpedoes for the battleship USS Pennsylvania (BB-38), a more valuable target as the flagship of the US Pacific Fleet.

As the air strike progressed, Sakamaki attempted to dodge the patroling destroyers and enter the harbor in time to join the fray, but got stuck on a coral reef. After several attempts, he backed the submarine off the reef, with one torpedo tube damaged.

Another attempt to navigate the harbor entrance resulted in the vessel getting hung high up on another reef, screws spinning helplessly in the air, where the destroyer USS Helm (DD-388) spotted her at 8:17 AM. Helm‘s gunfire actually knocked the submarine off the coral, and she escaped.

By now, HA. 19 had sustained enough damage that water was leaking inside. It reacted with the submarine’s batteries, which filled the interior with noxious fumes that sickened the two men. The air strike ended, but long after the Japanese pilots had flown victoriously back to their carriers, Sakamaki stubbornly refused to admit defeat.

Later that afternoon, the vessel crashed into yet another coral reef, smashing the remaining torpedo tube. In frustration, Sakamaki planned a kamikaze attack, telling Inagaki they would run into a ship and adding, “If we can’t blast the enemy battleship, we will climb onto it and kill as many enemies as possible.”

Kazuo Sakamaki becomes a prisoner of war (POW)

Sakamaki never got a chance to carry out his desperate plan. At nightfall, he discovered he was miles away from Pearl Harbor. Utterly exhausted, discouraged and weakened from the battery fumes, he set the HA. 19‘s course for the rendezvous at Lanai and fell unconscious.

He awoke the next morning to see land on the horizon. Believing it was Lanai, he ran his vessel aground on yet another reef while attempting to get closer. With no other option, he and Inagaki lit the fuse to scuttle the submarine and jumped into the sea. Inagaki drowned, but Sakamaki drifted unconscious to shore, where he awoke to see an American soldier guarding him. He’d earned the dubious distinction of becoming “Prisoner of War Number One.”

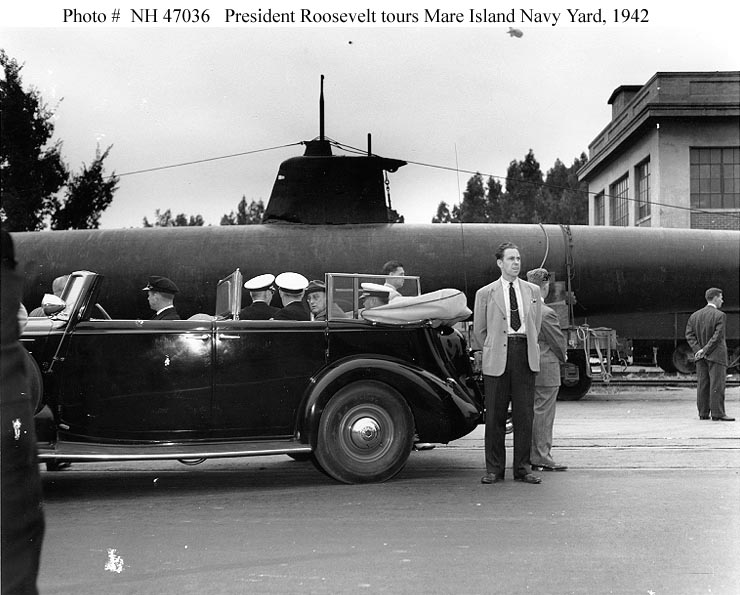

As it turns out, Sakamaki’s submarine hadn’t taken him to Lanai, but had, instead, drifted around Oahu. He’d run it aground near Bellows Field. Not only had he been captured, a great disgrace for a Japanese officer, but HA. 19 had also. Even worse, her explosives hadn’t detonated, so Japan’s top-secret weapon was now intact in enemy hands, ingloriously hauled onto the beach by a US Army tractor.

A somber end to Japan’s mini submarines

Of the expectations the Japanese had for the mini submarines during the attack on Pearl Harbor, that of death was the only one that came. The loss of the vessels and their crews was a somber ending to a daring mission that failed to accomplish its objectives.

Ironically, Yokoyama’s radio message led the Japanese to mistakenly believe the vessels had successfully contributed to the attack. Therefore, they gave the nine dead submariners a sizeable share of the credit and glorified them as heroes.

Some, however, weren’t overjoyed by the outcome. Masataka Chihaya later recalled, “A vice admiral who designed that craft said to me in tears, ‘Alas, I never would have designed such craft if they were to be used in such a manner. This is murder of the crews. What a pity!'”

What came of the mini submarines sunk at Pearl Harbor?

It was many years before all five mini submarines were accounted for. The first one was HA. 19. After being investigated by the US Navy, she was sent on a tour of the country to inspire people to buy war bonds. In 1991, Sakamaki visited the vessel that had caused him so much trouble. Today, HA-19 is a US National Historic Landmark and is on display at the National Museum of the Pacific War in Fredericksburg, Texas.

The one sunk by the USS Monaghan inside Pearl Harbor was used to fill in a pier construction project at the naval base. Sources differ as to the disposition of the crew’s remains, with some saying they received a military burial and others claiming they’re still inside the submarine.

Of the two “missing” submersibles, one was discovered in 1951 and the other in ’60.The former was missing both of her torpedoes, marking her as the one that fired upon the USS St. Louis. She’d been scuttled by her crew. The Navy, without advertising the fact, took the vessel apart and disposed of her at sea. The pieces were discovered in 1992 by the University of Hawaii’s Undersea Research Laboratory.

The mini submarine discovered in 1960 was found in Ke’ehi Lagoon by Navy and US Marine Corps divers during a training exercise. Upon being removed and inspected, she showed obvious depth charge damage. Further investigation also found her torpedoes were still in place, the escape hatch was un-dogged and there was no evidence of human remains.

After removing and disposing of the bow section, the US returned the remainder of the submarine to Japan, where a replacement bow was fashioned. The vessel is on display at the site of the former Imperial Japanese Naval Academy at Etajima.

Interestingly, the mini submarine that triggered the very first shots and first confirmed kill of the war between the US and Japan – albeit before the formal declaration of war – was the last to be found. It wasn’t until 2002 that the University of Hawaii’s Undersea Research Laboratory located the vessel sunk by the USS Ward.

More from us: 33 Rare Photos of the Japanese Attack on Pearl Harbor

These five weren’t the only Type A Kō-hyōteki-class submarines Japan built. Around 50 were completed before being replaced by the Type B. Between May and June 1942, some were used to attack vessels in Madagascar’s Diego Suarez Harbor and Sydney Harbor in Australia.