Japan wanted to become a global superpower

To grasp the reasons behind Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor, it’s essential to trace its roots back to the late 1800s during the decline of the Tokugawa shogunate. Simultaneously, under Emperor Meiji’s leadership, Japan embarked on a sweeping transformation aimed at establishing itself as a major global power.

Central to this shift was the modernization of its economy and efforts to secure greater access to vital natural resources. Yet, Japan faced significant challenges due to its limited territory and scarce raw materials, which hindered both economic expansion and population growth.

Consequently, Japanese leaders formulated strategies to extend their influence across the Indo-Pacific and surrounding areas, initiating what historians now view as an aggressive period of expansionism.

Growing Japan’s economic prospects during the early 20th century

At the dawn of the 20th century, Japan expanded its territory largely through military conflict. The Japanese military clashed with China (1894-95) and Russia (1904-05) to seize control of key resources and food supplies in Korea and Manchuria, a region in northeastern China.

These victories enabled Japan to achieve its objectives and earn recognition as a major global power through the Treaty of Versailles following World War I. In the years between the two World Wars, Japan shifted its focus to establishing peaceful relations with other nations, negotiating agreements to secure vital raw materials such as oil, steel, grains, and coal, particularly from the United States and Manchuria.

Things continued to get worse in Manchuria

In 1933, with no sign that Japan would be leaving Manchuria anytime soon, the League of Nations condemned the invasion, to which Japan responded by withdrawing from the international organization. Following this, Japan became more aggressive in expanding its territory and power, withdrawing from naval agreements that limited the size of its navy, and doubling the size of its armed forces within the span of five years.

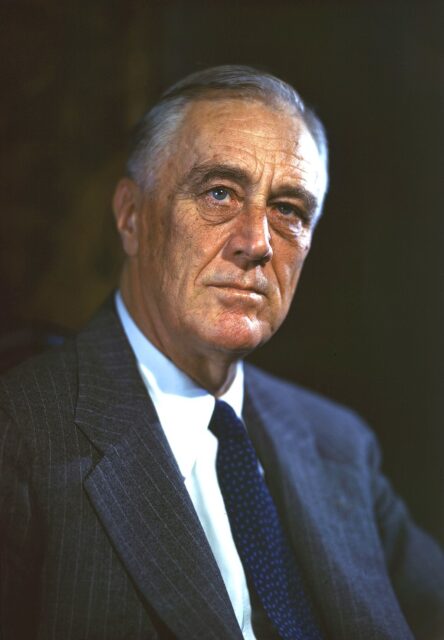

By October 1937, US President Franklin D. Roosevelt had become concerned enough about what was happening in Asia, as well as the ongoing Spanish Civil War, that he made a public statement, in which he said the “very foundations of civilization” were being “seriously threatened.” He was also worried that Japan would continue its expansionist movements into both the Philippines and Hong Kong, a move that would directly threaten the United States.

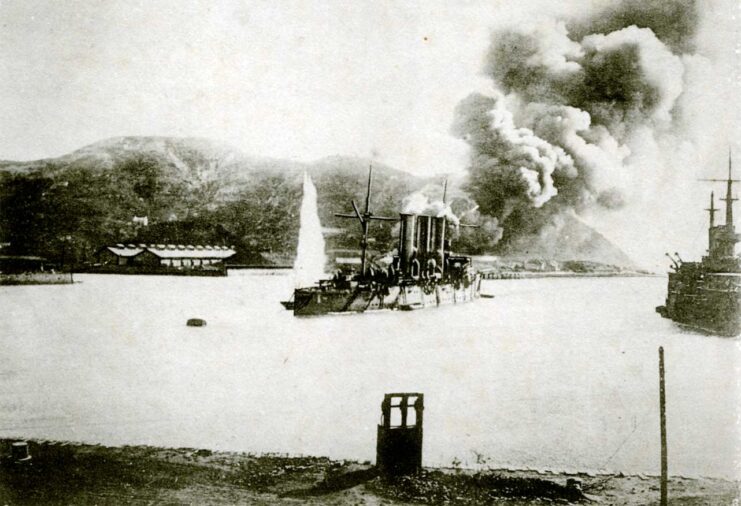

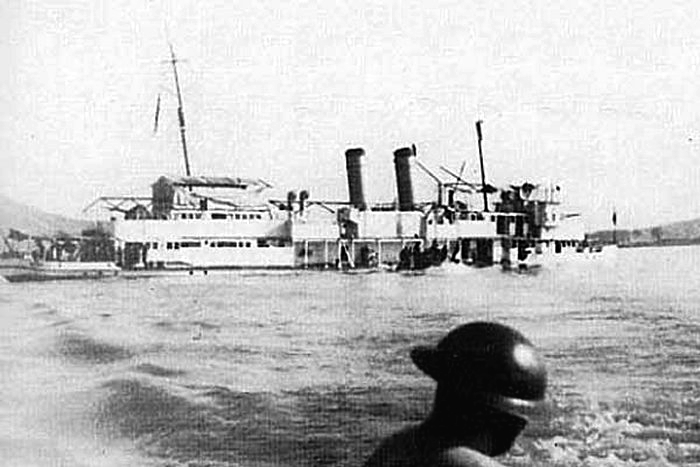

Tensions only began to grow in 1937-38, following the Nanjing Massacre, the bombing of the USS Panay (PR-5) and the Allison Incident. This led the US to increase trade to China, followed by economic sanctions upon Japan, which included the banning of the export of iron ore, aircraft materials and steel.

While all this was to make Japan wary of further action, it only angered the country’s government. In September 1940, it signed the Tripartite Pact with Germany and Italy, and a Neutrality Pact was signed with the Soviet Union the following year. While the latter was an ally of the US, the move meant Japan would be focusing its attention on southeast China, where American interests lay.

On top of all this, Japan signed a third pact, this time with Vichy France, which allowed its military to move into Indochina and continue the nation’s advance into southern Asia.

The United States froze all of Japan’s assets

In 1941, following Japan’s occupation of Indochina, the United States, Britain, and the Netherlands retaliated by freezing Japanese assets—an action that severed roughly 94 percent of Japan’s vital oil imports and dealt a severe blow to its economy. Facing a crippling shortage of fuel and other essential materials, Japan’s military strategists turned their focus toward capturing territories abundant in natural resources to sustain their war machine.

Japan’s leadership understood that such aggressive expansion would inevitably trigger a confrontation with the United States. Realizing they lacked the means for a drawn-out conflict, they crafted the “Southern Operation” strategy—a plan for rapid, coordinated strikes on key Allied positions such as Pearl Harbor, the Philippines, and British Singapore. The intent was clear: deliver a decisive opening blow, paralyze enemy defenses, and secure the resources necessary to keep Japan’s empire alive before the U.S. could fully mobilize.

Japan plans its attack on Pearl Harbor

Although several leaders contributed to the planning of the Pearl Harbor assault, it was Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto who played the most pivotal role. He spent months crafting a strategy aimed at crippling the U.S. Pacific Fleet and delivering a psychological shock to the American public.

Japan’s goal was to destroy America’s naval presence in the Pacific in a single, decisive strike. Leaders believed that such a blow would buy enough time to seize territories like the Philippines and British Malaya, and to fortify their newly gained positions before the U.S. could recover and mount a serious counteroffensive.

During this period, Japan continued diplomatic talks with the United States, but negotiations stalled. When the U.S. issued a 10-point statement outlining its stance, Japan’s military leadership concluded that diplomacy had failed—and the time had come to launch their attack.

Pearl Harbor wasn’t the only place Japan attacked

On December 7, 1941, Japan did as it had planned and launched a large attack on Pearl Harbor. The naval base wasn’t believed to have been a viable target, so the United States hadn’t provided it with near enough defensive measures, giving the Japanese a bit of an edge, along with the surprise nature of the strike.

What many don’t realize, however, is that Pearl Harbor wasn’t the only place targeted by the Japanese that day. While they may have been recorded as having occurred on December 8, given the time zone difference, strikes were launched on Guam, Malaya, Hong Kong, Singapore, Wake Island and the Philippines – all British and American territories.

In the Philippines, the Japanese took out almost an entire fleet of Curtiss P-40 Warhawks and Boeing B-17 Flying Fortresses at Clark Field, prompting an immediate response from the US. Heavy combat ensued, with the Japanese ultimately securing a victory in 1942. By then, the military had also secured control of Hong Kong, the Dutch East Indies, Guam, British Malaya and Singapore.

The majority of these territories remained under Japanese control until the final year of the Second World War.

Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor wasn’t all that damaging

While, at first, the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor looked successful, the fact of the matter was that a good portion of the US Pacific Fleet wasn’t stationed at Ford Island. While eight battleships and hundreds of aircraft were bombarded by bombs, the bulk of America’s naval power was unscathed, including tankers, repair facilities and ammunition sites.

More from us: Adolf Galland: The Luftwaffe Air Ace Who Survived Being Shot Down Four Times

Most importantly, the US Navy’s fleet of aircraft carriers wasn’t moored at Pearl Harbor. This came back to bite the Japanese in June 1942 when three carriers – the USS Yorktown (CV-5), Enterprise (CV-6) and Hornet (CV-8) – helped secure a crucial win at the Battle of Midway, which many view as the pivotal turning point of the war in the Pacific Theater.