Thirty-five ships steamed out of Sydney, Nova Scotia on October 5, 1940. A multitude of flags flew from their masts including Greece, Sweden, the Netherlands and the US. All the ships had a single goal: to make it across the treacherous Atlantic Ocean, avoiding enemy submarines. They knew their cargoes could keep Britain from falling to Germany, but they had no idea they were about to run into a terrifying new weapon: the Wolf Pack.

Convoys were the lifeblood of Britain after the war had begun in 1939. Ships carried goods from all around the world, bringing food, fuel, and war materials to her beleaguered citizens. From June 1940, Britain stood alone against Nazi Germany in Europe.

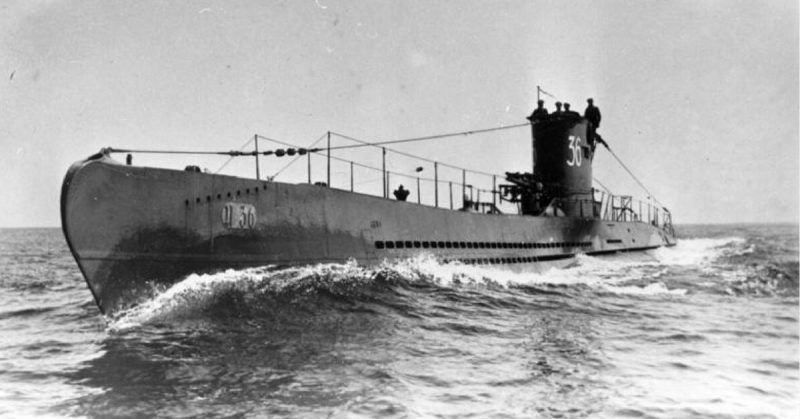

The German U-boats had been given orders to attack any vessel bound for Britain. By October 1940, individual U-Boats had been prowling the oceans for months, picking off Allied ships. To combat it, the British used large convoys with a military escort, in the hope they would prove a harder target for the attackers.

For the first leg of Convoy SC-7’s voyage, the vessels met up with their escort: HMCS Elk, a converted yacht, and HMS Scarborough, a sloop of war. The SS Winona had to return due to engine trouble, but the others headed towards the open ocean. The beginning of their journey went smoothly.

On October 7, HMCS Elk returned to Canadian waters, as it was not a suitable vessel for the deep ocean.

On the 8th, they ran into a heavy gale, and many of the ships became separated from the convoy. There had been difficulty in getting the merchant captains to partake in convoys. They were captains of their ships and resented being told what to do by the Royal Navy. Convoy Commodore L.D.I Mackinson worked diligently to regroup.

Submarines had spotted the ships during the gale but were unable to score any hits. They slowly trailed the convoy and contacted other subs in the area to advise of their position. By October 11 the weather had worsened even further, and the ships again became separated. One of them, SS Trevisa, wandered too far from the escort. On October 16, U-124 spotted her, and with a single torpedo, she was sunk. The next day, U-48 joined the fight, sinking the merchant ships Languedoc and Scoresby. U-38 sank the Greek freighter Aenos. Three submarines had arrived on the scene and had sunk four ships, but the real trap was about to spring.

On the night of October 17, the convoy was approaching the coast of Scotland. Three British escorts joined them for the last leg of their journey. They hoped it was the end of the submarine attacks.

However, lurking below the surface, seven U-boats pursued the vessels, waiting for their opportunity to strike. The men in the convoy were tense, continually scanning the horizon, looking for any sign of a submarine.

On the night of October 18, the four escorts moved around the slow-moving convoy, firing star shells into the sky. Each burst of white phosphorous illuminated a circle of water, which glistened as the sailors strained to see any movement.

At 2024 a massive explosion broke the tension. SS Creekirk, which had strayed away from the convoy, was destroyed by U-101. Loaded with heavy iron ore she sank quickly, taking her entire crew with her. The convoy tightened its defenses as the ships zig-zagged to deter an attack, but for two hours, nothing more happened.

Then at 2206 an explosion rocked the convoy, SS Niritos erupted in a plume of water. U-99 had attacked and was joined by the other six U-boats. The convoy ships frantically tried to evade them, but one after another, seven ships sank to the bottom. The escorts desperately searched for survivors, while still trying to fend off the attack.

The submarines darted in and out of the convoy, coordinating their attack. It prevented the escorts from returning fire. No one could tell where the attacks were coming from, but suddenly there would be an explosion, and another ship was lost. The convoy broke its formation, and the escorts tried to retrieve survivors. Over the course of about six hours, from 2200 on October 18 to 0400 on October 19, sixteen ships were sent to the bottom.

As dawn broke the U-boats left to attack another Convoy, HX-79, which had entered the area. In Convoy SC-7, only eight ships remained steaming toward their destination. The escorts, loaded with survivors, kept them in a tight formation, not wanting to risk another possible attack. By the 20th, the remaining ships and survivors were safely in port.

The seven U-boats sank twenty ships and damaged others. It was done without the loss of a single German sailor or ship. The almost complete destruction of Convoy SC-7 showed Britain how incredibly vulnerable her trade routes were to a concerted attack by a skilled foe. It showed Admiral Karl Doenitz, commander of the German submarine fleet, that the Wolf Pack worked.

From then on, his hunters scoured the oceans for a convoy to destroy; a new age of naval warfare had begun.