What did Operation K entail?

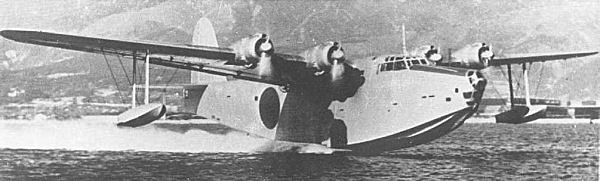

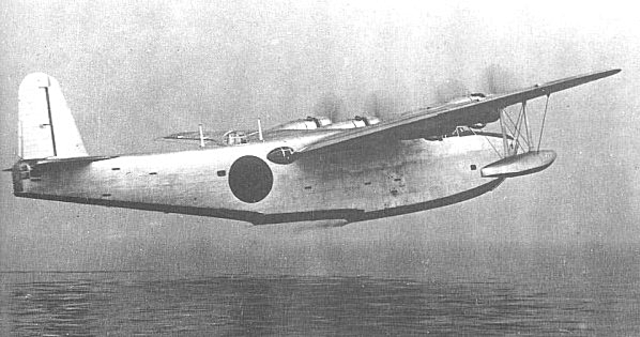

Operation K was set for the night of March 4, 1942, and was supposed to involve five massive long-range Kawanishi H8K flying boats. But because of logistical problems, only two aircraft were ultimately available for the mission.

These planes were originally earmarked for bombing runs against mainland U.S. targets like California and Texas, but first, the Japanese wanted to check on the repair progress at Pearl Harbor. The H8Ks were ideal for reconnaissance, and since each could also carry four 550-pound bombs, they had the ability to further disrupt the Pacific Fleet’s recovery efforts.

This mission was historic because it became the longest-distance bombing run ever carried out by just two planes, and it ranked among the longest bombing missions ever flown without fighter escorts. The round-trip journey from the Marshall Islands to Pearl Harbor and back covered more than 2,000 miles. To make this enormous trip possible, the Japanese placed fuel tanks at the French Frigate Shoals, where the flying boats could refuel before making the final 500-mile push toward their target.

Unable to approach Hawaii by sea

At first, the Imperial Japanese Navy viewed initial strike on Pearl Harbor as a major success. But soon after, aerial reconnaissance revealed that the U.S. Navy was recovering far faster than anticipated.

Determined to prevent another surprise attack, American forces quickly upgraded their offshore surveillance systems, making it extremely difficult for enemy vessels to approach Hawaii undetected. As a result, Japan shifted tactics, opting to send in long-range bombers for their follow-up strike. Their primary target was the Ten-Ten dry dock, where several damaged warships were undergoing repairs. By targeting these vessels, the Japanese hoped to stall the Pacific Fleet’s resurgence and buy the IJN more time to maintain its strategic advantage.

The operation was timed to coincide with a full moon, giving the pilots better visibility during their nighttime mission.

Kicking off Operation K

Before Operation K commenced, intelligence agents tracking Japanese movements spotted H8K flying boats preparing for the mission and promptly warned naval commanders stationed on Oahu. Unfortunately, these alerts were largely ignored. The mission was led by Lt. Hisao Hashizume aboard the lead flying boat, while Ensign Shosuke Sasao piloted the second. Compounding difficulties, the submarine I-23—responsible for providing critical weather updates—had become lost days earlier, leaving the crews without accurate information.

As the operation unfolded, radar stations on Kauai picked up the incoming planes, prompting a rapid defensive response. U.S. forces dispatched PBY Catalinas and P-40 Warhawks to intercept the Japanese aircraft. While low clouds helped conceal the H8Ks from straightforward detection, they also limited visibility for both sides. A miscommunication between the two flying boats caused them to lose formation, disrupting their coordinated timing.

The lead plane’s bombs landed harmlessly on a hillside near a Honolulu school, breaking a few windows but causing no injuries. The second aircraft missed Pearl Harbor entirely, releasing its bombs into the ocean. After the unsuccessful attack, the two flying boats retreated separately, touching down at different airfields in the Marshall Islands.

What was the outcome?

The main result of Operation K was that the United States discovered that the Japanese could still enter its airspace and leave without being stopped. The US Army and Navy blamed each other for the nighttime explosions near the school. The mission also caused concern about possible more Japanese attacks on the US.

More from us: Debunking Myths About the Japanese Attack on Pearl Harbor

Though a follow-up was planned for a few months later, it was eventually canceled because the Americans realized the Japanese were using the French Frigate Shoals as a base and had increased patrols in the area.