The incredible work of Britain’s World War Two code breakers at Bletchley Park is widely celebrated. But its precursor – the naval intelligence of Room 40 – played an important part in the First World War. It was staffed by a number of extraordinary people.

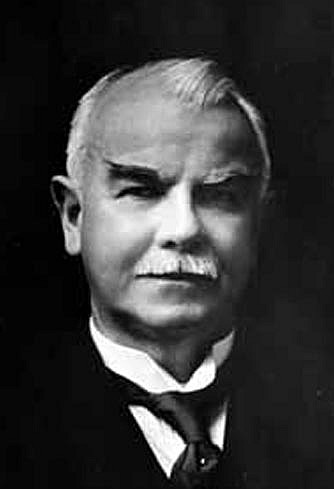

Sir Alfred Ewing

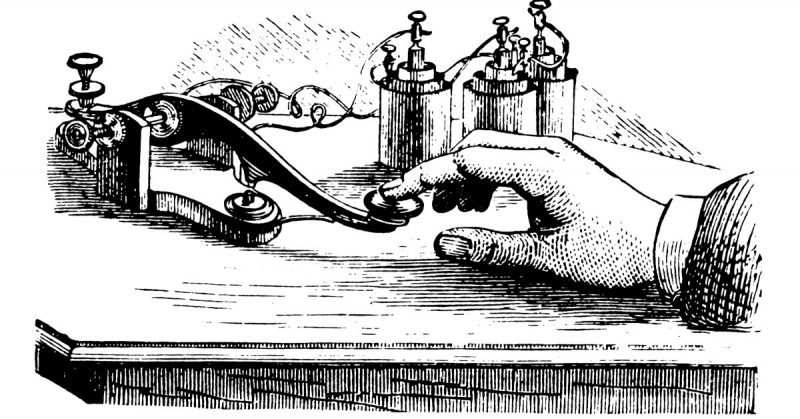

On the first day of the war, the British Admiralty found themselves with a growing pile of intercepted German signals and a growing problem – they couldn’t understand them. To solve this problem they established a new section, headed up by the director of Naval Education, a man with a keen amateur interest in cryptography – Sir Alfred Ewing.

A soft-spoken Scot who always dressed in an immaculate gray suit, Ewing had worked as a research engineer and the Professor of Mechanical Engineering at Cambridge. He had received the Gold Medal of the Royal Society for his research in magnetic induction and been knighted for his work as an educator. He brought the perfect combination of leadership and sharp analysis to the role.

Recognizing his own ignorance about ciphers, Ewing set to work learning more. He studied the code books of the Post Office and the insurance company Lloyds as well as old books on code making.

He then set about recruiting a group of men to work with him.

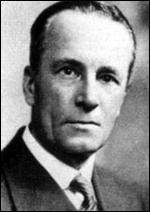

Alexander Denniston

Due to the secrecy of his work, Ewing could not openly advertise for recruits. Instead, he tapped into the old boys’ network of Royal Navy connections, asking trusted teachers at the naval colleges to recommend men.

One of the first to be recruited was Alexander Denniston. Another quiet Scot, Denniston was also an accomplished sportsman, having played hockey in the 1908 Olympics.

More importantly for the task in hand, Denniston was a brilliant linguist and fluent in German. Having studied at both the Sorbonne and the University of Bonne, he had been thoroughly immersed in the business of interpreting from one language to another.

Denniston only meant to join Ewing’s team for a short time. After all, everybody expected the war to be over quickly, and then the team’s work would be done. Instead, he became a fixture among Britain’s code-breakers, remaining in the profession until 1942.

Charles Rotter

During the first few months of the war, the British Navy were able to capture three major code books used by their German opponents. In theory, these could be used to understand the orders of every ship in the German fleet. But there was a problem. While some of the messages appeared to be weather reports, the rest remained unreadable even after initial decoding.

The solution was found by Charles Rotter. As well as being the Paymaster of the Fleet, Rotter was an expert in German. On studying the messages, he realized that there were several layers of code in play. Once encoded, the letters in the messages had been switched using a substitution key.

Searching through the messages, Rotter looked for the most common words and sets of letters to be expected in German signals. Once he identified common letters, he used these to work out the rest. Together with his expertise on naval affairs, his knowledge of German, and the code books, this allowed him to decode the signals within a week. The substitution table he provided allowed his colleagues to reach the same understanding he had. Soon their whole focus was on naval signals.

George Young

In 1915, the remit of the British cryptographers was expanded. As well as reading naval signals, they would now take a step so ungentlemanly it had previously been unthinkable – deciphering German diplomatic messages.

For this, a new group of analysts was needed, men with a different sort of experience. The first to be recruited, and the man who helped select the rest, was George Young.

Unlike the other cryptographers, Young had the air of a spy. Suave, mysterious and sophisticated, he was ready to take any step to defeat the enemy.

This attitude had previously been brought to bear in the diplomatic service. After studying in France, Germany, and Russia, Young became a diplomat. He served in this capacity in Athens, Belgrade, Constantinople, Madrid, and Washington. He understood languages. He understood diplomatic culture. Above all else, he understood how to look for hidden meanings.

It was this new focus on diplomatic messages that would bring one of the greatest coups of the war.

Nigel de Grey

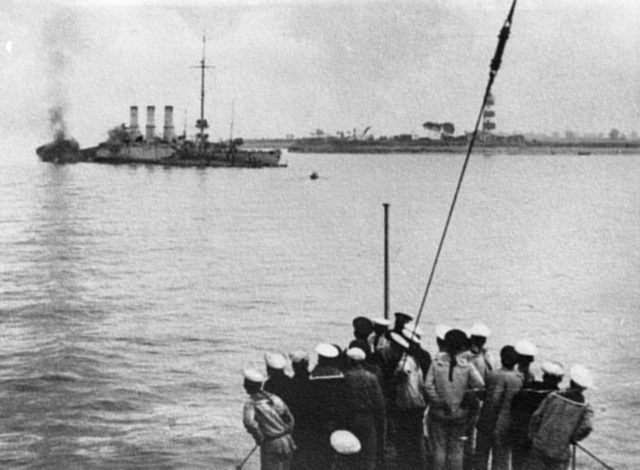

“Do you want to bring America into the war?” These were the words with which Nigel de Grey addressed the Director of Intelligence, Captain Reginald “Blinker” Hall, on the 17th of January, 1917. It was the beginning of one of the most significant pieces of work by the code breakers.

De Grey, one of the leading British code breakers, had been working with the Reverend William Montgomery on a message. Though it was still only partially deciphered, it was so important that he went straight to Hall with the news.

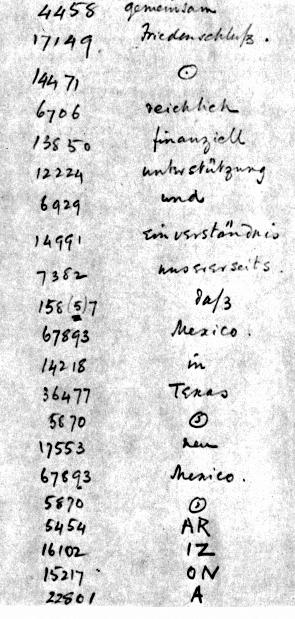

A message from the German Foreign Office to the German ambassador in Washington, the signal had been encrypted twice and sent through a series of three separate channels. The last stage in its journey involved it being tagged onto another message transmitted via the US State Department. The Americans allowed the Germans to use this route as long as they did not use it to discuss the war.

This message, later known as the Zimmerman Telegram, was all about the war.

If the transmission of the telegram through the American State Department was provocative, its contents were even more so. It laid out plans to begin unrestricted submarine warfare on the 1st of February, and to join with Mexico in attacking the USA if the Americans should enter the war.

At first, Hall had de Grey and his colleagues remain quiet about the telegram. But after the 1st of February, when it became clear that more was needed to push America into the war, Britain presented the Americans with the Zimmerman Telegram. It stirred up anti-German feelings among Americans and was used to bring the USA into World War One. That message helped to achieve exactly what de Grey had suggested.