The most powerful gun to be fielded in the First World War was the German Paris Gun. Several of these guns were produced and used to bombard the French capital in the final year of the war.

The Paris Gun was not unique. Several other super-guns had been fielded during the war, and others would be built later. It was notable for its novelty more than its effect on the war.

Superguns of the First World War

Before the arrival of the internal combustion engine, artillery with a caliber greater than 210 mm could not be fielded. They were simply too heavy for horses to pull into position.

By the start of the First World War, the internal combustion engine had changed that. Larger weapons were designed, in particular by the Central Powers.

The first was produced by Skoda, an Austro-Hungarian company. A 305 mm howitzer, it was transported in three parts, each towed by a tractor. Several of these howitzers were loaned to the Germans, who used them to pound Belgian forts in 1914. They also proved valuable on the Eastern Front, where the Austrians used them to flatten Russian fortifications.

The attacks on Belgian fortresses also featured the first German super weapon. Built by the Krupp family firm, perhaps the most influential gun makers of the 19th and 20th centuries, it was named Big Bertha after the wife of the head of the business. A 420 mm howitzer, at first it could only be moved by rail. The Krupps hurriedly adapted it for road transport when the war broke out.

The first use of these super weapons was a success for the Germans, enabling them to smash supposedly impregnable defenses. The Krupps worked on larger guns throughout World War One, and by 1918 they had produced the Paris Gun.

The Barrel

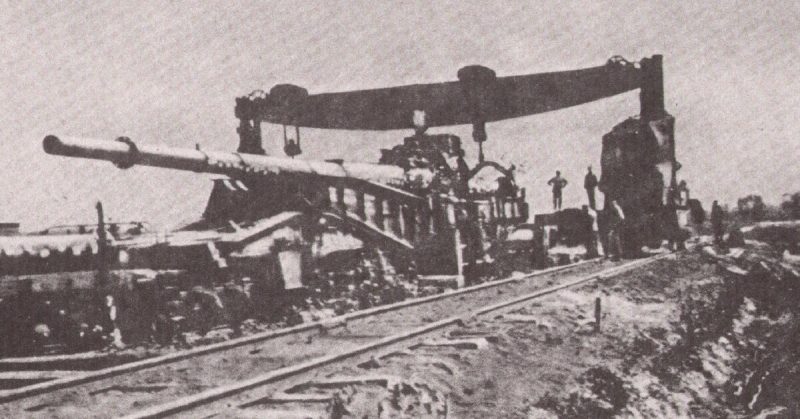

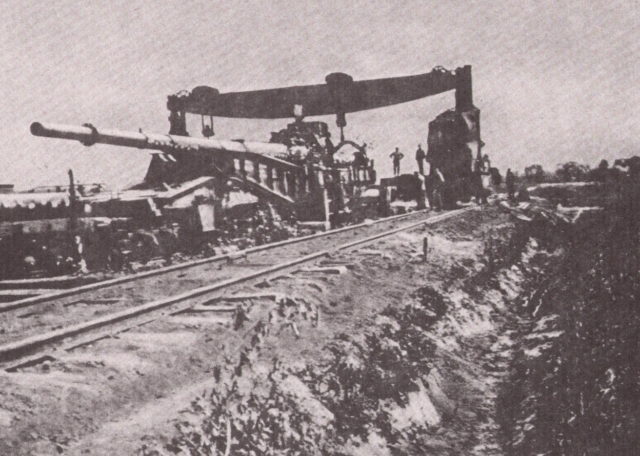

The starting point for building a Paris Gun was the barrel of a Long Max, one of the other large artillery pieces of the era. Originally designed for use on ships, the Long Max was used as a railway gun. Their barrels had a caliber of 15 inches and were 55 feet, 10 inches long.

This barrel was reamed out and an eight-inch caliber tube inserted. As well as reducing the caliber of the barrel, it extended its length by 36 feet, 11 inches. An additional length of an unrifled barrel at the end brought the entire weapon to a massive 112 feet. It weighed 138 tons.

Due to its length and weight, the barrel was braced to stop it drooping or vibrating when fired. It was mounted on a railway carriage and fired from concrete emplacements that had turntables to direct the gun.

Ammunition

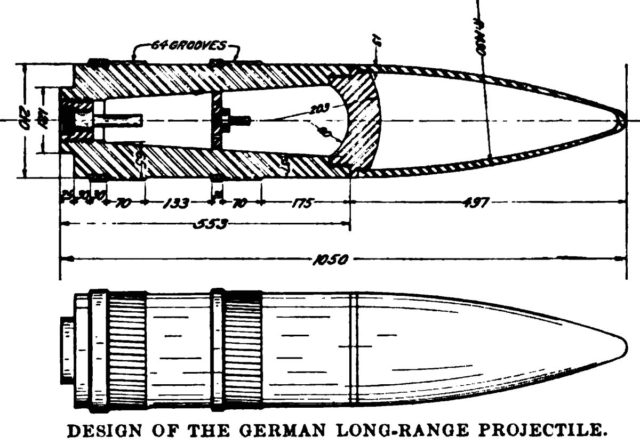

This specially constructed weapon needed special ammunition.

A slow-burning smokeless powder was developed to fire projectiles from the gun. A chamber 15 feet, five inches long was filled with this explosive.

The shells were 38 inches long, and each weighed 234 pounds. Due to the force involved in firing the gun, the shells had to have unusually thick outer layers of steel leaving space for a relatively small amount of explosive for their size – around 15 pounds of TNT. When they hit, they exploded into a few big parts, rather than a large number of smaller bits which enabled other shells to do so much damage. Together this limited their impact.

The power of the gun created such strains that the barrel was worn away shot by shot. The shells were made to counter this. Each batch of 65 was fired in a specific order, with each shell slightly larger than the last, to take account of changes in the barrel. The quantity of explosive firing the shells was also altered with each shot. After 65 rounds had been fired, the barrel was removed and sent back to the Krupp works to be re-bored. When it returned, it came with a fresh set of 65 shells.

Firing the Gun

At 0715 on March 23, 1918, a Paris Gun opened fire on its target for the first time. Firing from 75 miles away, it launched its shell 23 miles up into the air, so far that it reached the stratosphere. It took three minutes to reach its target – the city of Paris.

So unexpected was the arrival of the shell that Parisians initially assumed they were being bombed from an airship. Later enough pieces of casing were gathered to identify the explosives as shells rather than bombs.

From then until August 9, the guns shelled Paris. It was an arduous process. The physical effort of loading the gun was huge. There was also considerable intellectual effort involved. In firing over such a long distance, a range of factors had to be considered when targeting. These included air currents, temperatures at different altitudes, which shell was being fired, and the earth’s rotation.

Firing at maximum capacity, the Paris Gun could fire only around 20 shells a day.

The guns killed 256 people, 90 in a single hit on a church on Good Friday. They caused fear and property damage but made little difference to the war effort. In many ways, they were still an experiment rather than an effective weapon.

After the War

The Paris Gun was first used as the Germans were launching their spring offensive of 1918. By the middle of the summer, they had lost momentum. By the autumn, the Allies were advancing, and the war would soon be over.

Rather than let these guns fall into enemy hands, the Germans destroyed both the guns and the plans for them. They were meant to hand one over as part of the armistice but never did.

Under the peace terms, Germany was banned from making such guns. Krupp continued to work on theoretical models, which were then produced and refined under the Nazi regime. The successor of the Paris Gun bombarded the British south coast during the Second World War.

Sources:

William Weir (2006), 50 Weapons that Changed Warfare.

Wikipedia – accessed 19th December 2016.