Edith Cavell was a British nurse during World War I, with a history that was tragically cut short. Before her execution at the hands of the Germans, however, she managed to help more than 200 Allied soldiers and citizens escape from the Germans that had overrun Belgium.

For this, she was accused of treason, but, shortly after, her case was widely known world-over, as she became a press sensation.

The Start of a Medical Career

Born in 1865, Cavell was not born to a wealthy family, but they were known for their charity. She went to a girls school before becoming a governess, where she traveled to Brussels to work for a family for five years.

After, she went to London Hospital to train as a nurse, working in various medical institutions around the country. Then, at the age of 42, she was asked to be the matron of a nursing school in Brussels. There, she found great success publishing a nursing journal, as she went on to train nurses at 40 different establishments in Belgium. The Red Cross took over her nurse training school at the outbreak of World War I.

World War I

As soon as the Germans overran Brussels, Cavell began assisting British soldiers as best she could by providing them with hidden shelter until she could help arrange transport to the Netherlands. She was associated with Prince Reginald de Croy, who would provide wounded British and French soldiers with false papers and access to people like Cavell. She would then help them with lodging and logistics until they reached Dutch ground.

Everyone involved was violating German military law through this practice, and suspicions were raised. Cavell was becoming more of an outspoken public figure in medical circles for her extensive work in nursing.

Unfortunately, one of the people involved in harboring the soldiers was a collaborator with the Germans and gave them her name. She was held in prison for ten weeks, two of which were in solitary confinement.

During this time, Cavell gave three depositions. She admitted she had sheltered and assisted at least 175 people who were either Allied soldiers or looking to escape joining the war.

She was sentenced to death due to her treason. Some claimed Cavell was protected under the First Geneva Convention, as she was medical personnel during wartime. However, it was argued that any protection was canceled out if an individual was using their medical status as a coverup.

The British government did want to help Cavell as she was their citizen but felt they were powerless, and any attempts on their part would result in worse treatment for Cavell. As it was 1915, and the US had yet to join the war, they decided to intercede on behalf of Britain.

The First Secretary of the US Legation at Brussels spoke with German officials, telling them that executing Cavell would only worsen their already poor reputation with the rest of the world. He went so far as to compare the Cavell execution with the Lusitania sinking.

Unfortunately, the German response was not positive, with one German Count saying he would rather Cavell was executed than harm come to any German soldier. He also stated that he wished he had “three or four [more] old English women to shoot.”

However, some Germans did express a desire to pardon Cavell, for her honest admission of guilt, as well as her work as a nurse, during which she did help German soldiers as well as Allied soldiers.

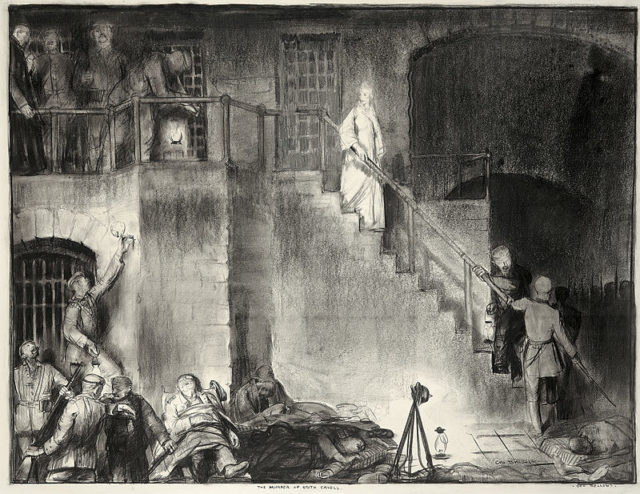

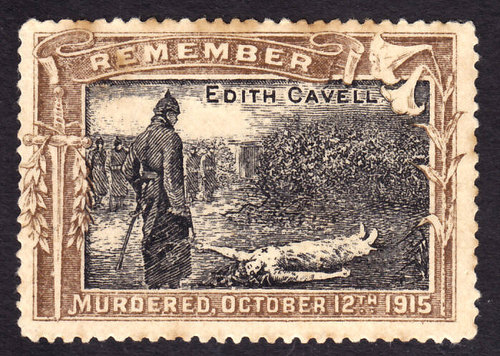

Leading up to Cavell’s execution date, representatives from both the United States and Spain pleaded with Germany to at least postpone the shooting. However, on October 12, 1915, Cavell, along with four other Belgian prisoners, were taken to a shooting range where they faced two firing squads. Eight executioners were for the four other men; eight solely for Cavell.

Press Coverage

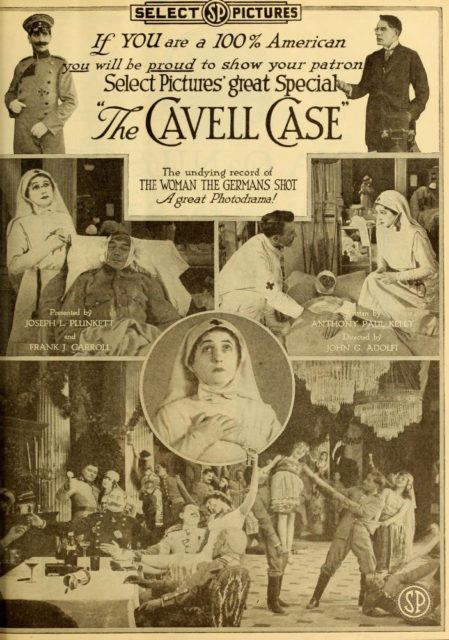

Press coverage of Cavell’s case did occur during her imprisonment and trial. However, her appearance in the media significantly increased after her execution. Her image and story appeared in tons of newspapers, pamphlets, posters and books. She became a very popular figure in British propaganda. In US propaganda she was used to help Americans change their opinion about the war.

Her popularity is mainly attributed to the fact she was a woman and a nurse, as well as very courageous during her trial. Her death also represented a sense of German barbarism and wickedness. Propagandists hoped she would inspire a lust for revenge on the battlefield, and that she would stand for all innocent British women that were in danger of being killed by the Germans.

Unfortunately, some of the stories circulated in the media after her death were untrue. One such story said that Cavell refused to wear a blindfold in front of the firing squad. Another that she fainted and a German officer approached her prostrate body and shot it himself with a revolver until she was dead.

Regardless of what was true or not, she became the most famous female figure of British WWI propaganda and the most famous British female casualty in the war. The American secretary was indeed correct that her execution would rank as high in the news as the Lusitania sinking.

Despite public sentiment, the German government held true to their decision and maintained that they had acted reasonably. They felt Cavell’s execution was necessary and just, and that war crimes could not be overlooked simply because the offender was a woman. They also were worried that if they had released Cavell, more women would have joined, thinking they could participate in the war without fear of being punished as a man would be.

Today, there are at least 11 memorials to Cavell throughout Europe for her service in the war.