WWI was most notable for trench warfare, the conditions of which were often so horrific that it’s hard to imagine what these soldiers endured, day after day. Despite such horrors, something strange happened on 25 December 1914, one that threatened the governments of both sides and the progress of the war. The threat? Christmas.

The Germans started the war in July 1914. Having taken Belgium and a slice of France, they were confident they’d take Paris just as quickly and that the whole thing would be over by Christmas. The British and the French, as well as their allies, thought the same. They were all wrong.

The Allies repelled the German advance at the First Battle of the Marne from September 5 to 12, forcing them to retreat to the Aisne valley where they dug themselves in. The Allies reached them on September 13, and the First Battle of the Aisne began. It ended in a stalemate.

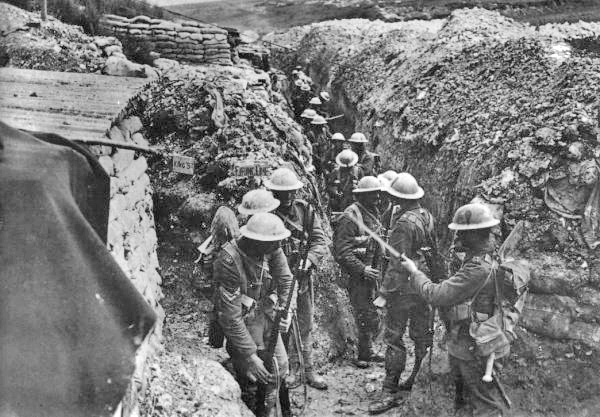

The Germans wanted to reach the Sea; the Allies wanted to prevent that, so each dug trenches to try to outflank the other, separated by several meters called no man’s land. And so it went: the Allies blocking the Germans by digging trenches further east and west, and the Germans doing the same, till both reached the North Sea.

By the start of December, each side had dug over 250 kilometers of trenches and had suffered heavy losses in the first months of the war. Britain lost almost 100,000 men. In August alone, France had lost double that number, roughly the same as Germany.

Not all the deaths were due to combat, however. Disease was rampant in the cold, the cramped and unsanitary conditions, as well as the constant mud and water. There was also trench foot: when feet are constantly soaked. Left untreated, gangrene and death results.

Sometimes, trenches caved in, burying the men they were built to protect. But even the best-made ones could be death traps because if hit directly, they focused bomb blasts, causing more damage than if they had gone off in open spaces. Often, the men could only watch helplessly as the bombs fell toward them – unable to run because they were so tightly packed together.

Finally, there was the propaganda. Each portrayed the other as unfeeling brutes because it’s easier to kill a person if you stop seeing them as human. Despite this, there were occasional, hour-long ceasefires so that everyone could dispose of their dead.

On the evening of December 24, however, the Twilight Zone descended. No one is sure where it started exactly, but it’s believed the first incidents began in Flanders before spreading to the rest of the Western Front.

The Germans started singing Christmas carols. Then flashlights and cigarette lighters came on – a dangerous thing to do since it allowed the Brits to pinpoint exact enemy positions.

But while most of the Brits understood no German, they recognized the tunes. Some even sang along in English. As they did, more flashlights and lighters were lit among the German line. None of the Brits had the heart to shoot them.

On Christmas morning, Pioneer Sergeant J.J. ‘Nobby’ Hall, stuck a sign on a stick which read “Merry Christmas,” and waved it over the trench. A similar sign was waved over the German line before it popped back under.

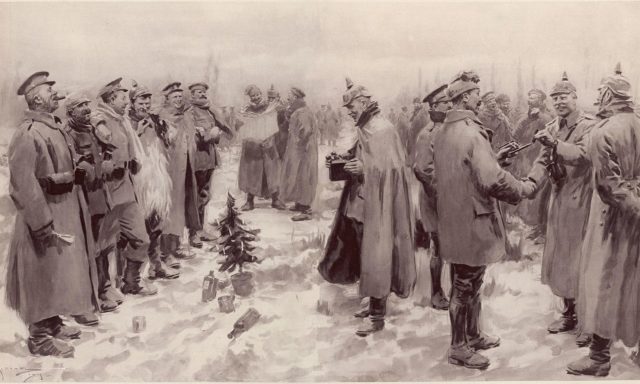

Then at noon, a German jumped over his trench as British rifles took aim. The man put his hands up and began walking unarmed across no man’s land. Private Ike Sawyer went out to meet him. In the middle, they shook hands. From the German line, more soldiers stood with their hands up and the Brits met them in the middle.

Some Germans stuck candles in small pine trees and used that as a white flag while they crossed over. Gifts of food, cigarettes and clothes were exchanged. Football games were played, and the Germans who played against the Scotts couldn’t stop laughing when they found out the latter wore nothing under their kilts.

Such camaraderie only happened in the British sectors, however. The French were in no mood to fraternize with the enemy that had seized portions of their country. On the Eastern Front, the Russians (who were allied with the British and the French) did not celebrate Christmas till January 7.

Since many of the Germans worked in Britain before the war, most spoke some English. Some had even met, such as Captain Clifton Stockwell, who found himself shaking hands with a German soldier that had waitered at a restaurant he frequented. Another Brit let his pre-war German barber cut his hair and shave his beard.

Despite the camaraderie, they had an unspoken rule: neither could see the trenches of the other to prevent revealing their weaponry and layout. Not all the British-German fronts saw peace, however, and fought through Christmas Day.

The governments of both sides were mortified. They threatened dire consequences for those who fraternized with the enemy, but it did no good for those who were already on friendly terms.

The greatest fear was that the war might end on the Western Front. Worse, with anti-royalist and pro-communist sentiments growing in some countries, what would happen if soldiers dropped their weapons and brokered a permanent peace?

For those who did reach out, the truce usually held until December 26. Along some fronts, it held out longer, but for Private Archibald Stanley, it ended the day after Christmas. His commanding officer, fearing a mutiny, allowed the truce to hold on Christmas. The next day, he ordered his men to fire at any Germans still standing on no man’s land. He was ignored.

By late afternoon, fearing he was losing control, the officer shot and killed an unarmed German soldier. Things went downhill from there. As the war progressed and new weapons like poison gas were used, neither side felt any desire for a truce.

On 11, November 2008, a monument to the Christmas Truce was set up in Frelinghien, France. It was attended by the descendants of those WWI veterans who dared to let the spirit of Christmas infect them, if only for a day or two.