The origin of mine warfare dates back all the way to the mid-19th century, during the American Civil War. In December 1861, Confederate officer Maj. Gen. Leonidas K. Polk oversaw several men as they loaded explosives into iron containers and buried them along two routes leading into Columbus, Ohio.

Luckily, the Union soldiers discovered the cache of explosives and dismantled them before they were detonated, but Polk and others had become infatuated with the idea of using mines to sway the outcome of the conflict in their favor. Half a century later, landmines took on a whole new level of lethality during the First World War and, in particular, the Battle of Messines.

Planting Allied landmines along Messines Ridge

The area of Ypres, Belgium saw some of the most prolific battles of the First World War. and it’s where mining really took shape. The Germans first captured Messines Ridge in 1914, which afforded them a high-point to clearly observe Allied movements. After suffering heavy casualties, the Allies began mining against German-held areas in West Flanders. Explosives were placed 15-20 feet below the surface, beneath the enemy territory.

By the fall of 1915, British Expeditionary Force (BEF) Engineer-in-Chief Brig. George Fowke suggested they build galleries – a series of underground tunnels – 60-90 feet below the ground. He proposed they be dug underneath the German transportation routes in Ploegsteert–Messine, Vierstraat-Wytschaete and Kemmel-Wytschaete. Two tunnels were also dug between the Douve and Ploegsteert.

The galleries were supposed to be over 1,000 yards long, but the longest wound up being only 720 yards in length. The men charged with digging them served as part of “tunneling companies” – soldiers recruited for their excavation skills – and faced harsh conditions, including struggles with groundwater and other geological setbacks.

After months of digging, the BEF’s tunnel system was complete. The miners filled the galleries with 454 tons of ammonal and gun cotton, while several mines were placed throughout the Messines. The largest were located at St. Eloi, loaded with 95,600 pounds of ammonal divided between two locations: Maedelstede Farm and Spanbroekmolen, the highest points in the area.

German forces came within meters of Allied mines

The Germans were also digging their own network of tunnels – in fact, one came within meters of the British mine chambers. They also unearthed a mine at La Petite Douve Farm well before the Battle of Messines began.

The Germans weren’t totally oblivious to the Allies’ mine plans, as spies and air-based reconnaissance had picked up on the heavy activity around Messines Ridge. They were also aware that the Allies were planning to use the mines as part of a ground-level attack. After debating leaving the area lined with mines, they decided an assault wasn’t imminent. If one happened to occur, they were confident enough in their defenses, even though some officers wanted to retire to a safer location.

Battle of Messines and the boom heard across Europe

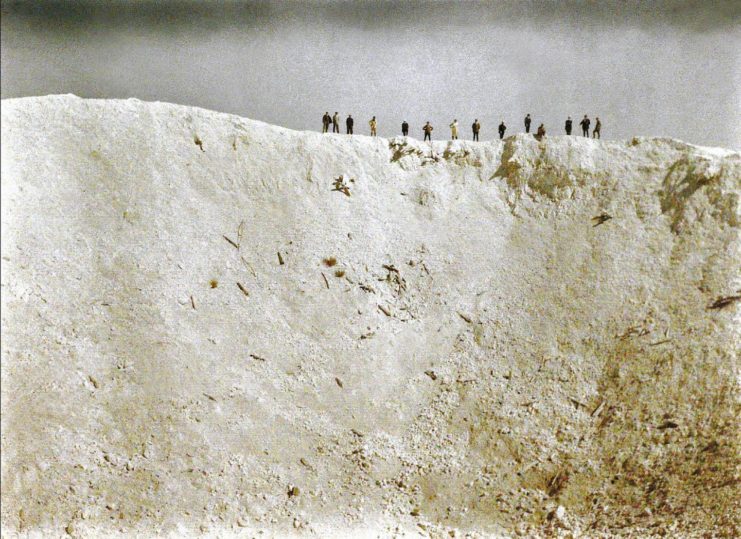

Just before dawn on June 7, 1917, British artillery halted as the sound of nightingales singing broke through the silence of the battlefield. At 3:10 AM, the mines along the Messines were all fired within 20 seconds of each other, creating a massive boom as the largest non-nuclear explosion tore through German territory.

Some even suggested it was the loudest man-made sound in history, supposedly heard as far as London and Dublin.

“The German troops were stunned, dazed, and horror-stricken if they were not killed outright,” recalled journalist Philip Gibbs. “Many of them lay dead in the great craters opened by the mines.” The explosion was deadly, killing as many as 10,000 German soldiers between Ypres and Ploegstreert.

The troops from the United Kingdom, Canada, Australia, Ireland and New Zealand completed most of their objectives within hours of the battle’s commencement, capturing 7,000 German soldiers and allowing the Allies to retake Messines Ridge.

More from us: Battle of Tannenberg: Annihilation of the Russian Second Army

The Allies had created 26 mines and all but seven were set off, resulting in the detonation of one million pounds of explosives. The months of work and meticulous preparation ultimately paid off with very few losses. Messines is still regarded today as one of the major contributors toward the Allied victory in World War I.