Born from the intense pressures of the Cold War, the Sprint missile was designed to solve one urgent problem: stopping Soviet nuclear warheads in the final seconds before impact. To meet that challenge, U.S. engineers created an interceptor capable of astonishing performance, able to rocket past Mach 10 in just a few seconds—placing it among the fastest missiles ever built.

Sprint was fielded as part of the Army’s Safeguard Program, a brief defensive effort intended to protect American ICBM silos from attack. The system became operational in 1975 but was shut down barely a year later as strategic doctrine shifted and arms control agreements reduced the perceived need for such defenses. Though it never fired in combat, the Sprint missile endures as a striking example of Cold War innovation, remembered for its extreme speed and the bold engineering that made it possible.

Last-ditch defensive strategy

Issues with the Nike Zeus

During the development of the Nike Zeus, it quickly became clear that the ABM system had several weaknesses that made it susceptible to potential defeat.

The system depended on 1950s-era mechanical radar, which limited its ability to track multiple targets simultaneously. Reports from that time indicated that four warheads could give a 90 percent chance of destroying a Nike Zeus base. Although this initially seemed like a manageable risk, the falling cost of ICBM production made it increasingly probable that the Soviet Union would consider using them against the United States.

As time passed, more issues emerged. After nuclear tests in space in 1958, it was discovered that radiation from warhead detonations could spread over vast areas, disrupting radar signals at altitudes above 60 km. A high-altitude explosion triggered by the Soviets above a Nike Zeus site could interfere with detection capabilities, making it too late for a counterattack.

Furthermore, the Soviets could place radar reflectors on their warheads, creating multiple false targets.

The Nike-X replaced the Nike Zeus

Under the direction of then-Secretary of Defense Neil H. McElroy, the Advanced Research Projects Agency (ARPA) studied key issues related to missile defense. Their research showed that high-altitude nuclear explosions and radar decoys became less effective in the lower atmosphere because of increasing air density. To solve this problem, experts recommended waiting until the warhead dropped below 60 km, where radar could once again track it.

But this created a new problem—warheads were traveling at speeds of Mach 24, meaning any intercepting missile had to be just as fast to stop them before impact.

As a result, Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara, who took over as Secretary of Defense after McElroy, advised President John F. Kennedy to redirect funds from the Nike Zeus project to improve ARPA’s system. His reasoning convinced Kennedy, leading to the development of Nike-X.

Introducing the Sprint missile

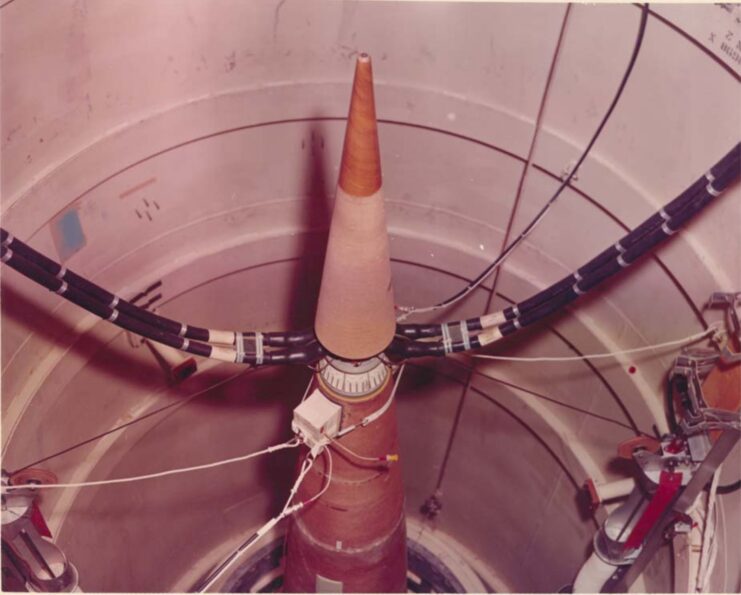

The Sprint missile took center stage in the Nike-X program. Armed with a W66 thermonuclear warhead, its mission was to intercept re-entry vehicles (RVs) at a distance of 60 km.

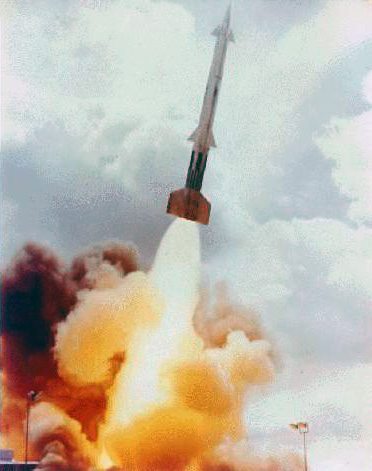

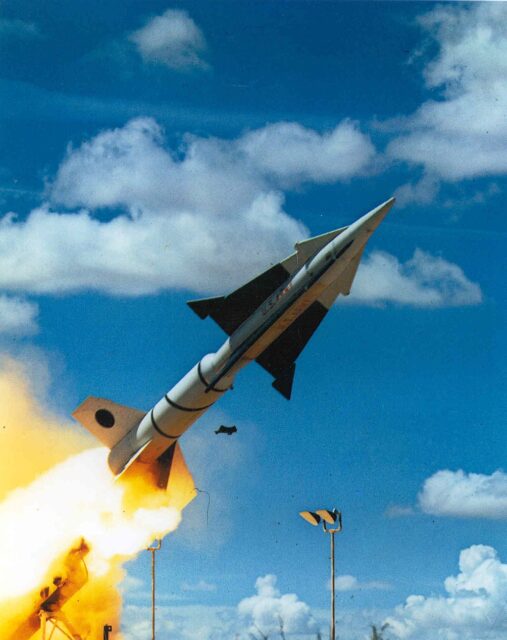

Measuring 27 feet in length and weighing 7,500 pounds, the Sprint relied on a precise launch sequence. Initially housed in a silo, the missile was launched when its cover was blown off by an explosive-driven piston. Once airborne, it would adjust its trajectory toward the target, guided by ground-based radio command guidance. This tracked incoming RVs via phased array radar and led the missile to its destination, where it annihilated its target through neutron flux.

The Sprint’s performance was nothing short of remarkable. Engineered to accelerate at a staggering 100 g and reach Mach 10 in a mere five seconds, it operated at low altitudes where its skin temperature soared to 6,200 degrees Fahrenheit. To counter this, an ablative shield was employed, creating a distinct white glow around the missile as it traversed the sky.

Navigating through such extreme conditions necessitated powerful radio signals capable of penetrating the plasma enveloping the missile, ensuring precise guidance toward its intended target.

HIBEX missile

The High Boost Experiment (HIBEX) missile is considered a kind of predecessor to the Sprint missile, as well as its competitor. It was another high-acceleration missile designed in the early 1960s, and it actually provided a technological transfer to the Sprint development program.

Unlike the Sprint missile, the HIBEX had a high initial acceleration rate of nearly 400 g. Its role was to intercept RVs at an even lower altitude – as low as 20,000 feet. Unlike the Sprint, it featured a star-grain “composite modified double-base propellant” that was created by combining zirconium staples with aluminium, double-base smokeless powder and ammonium perchlorate.

Sprint II missile and the end of the Nike-X program

Over time, the Nike-X evolved into the Safeguard Program, prompting the Los Alamos National Laboratory to explore alternative warheads for a fresh design. Subsequently, efforts were directed toward enhancing the Sprint II missile.

By 1971, the Sprint II became an integral part of the Safeguard Program, serving as a protective measure for Minuteman missile fields. Its interceptor boasted a slightly reduced launch dispersion, compared to its predecessor, which enhanced hardness and minimized miss distance for improved accuracy.

Despite ongoing optimization efforts by Los Alamos to refine the design, the operational lifespan of both missiles was relatively brief.

During the 1970s, shifts in the ABM policies of both the US and the Soviet Union raised doubts about the effectiveness of the Safeguard Program. It was deemed unnecessary and expensive, leading to its cancellation. The official discontinuation date is unclear, but reports persisted until 1977.