Just the sight of the big guns that at one time guarded the coasts of southern England in World War II would intimidate the faint of heart.

Winnie and Pooh not only dueled with Nazi cannons across the English Channel but tried to destroy them, in addition to firing on German ships transiting the Channel.

Placement of the British 14-inch naval guns, which could propel a 1,590-pound shell as far as 27 miles when an extra charge was added, were to counter Hitler’s efforts to employ them for not only coastal defense but as a tool to soften up the British prior to Operation Sea Lion — the invasion of Britain.

Between the First and Second World Wars, the maximum range of heavy artillery had grown substantially.

The first big gun, Winnie, named after British Prime Minister Winston Churchill, arrived one week after German forces took control of the French coast near Calais in late May 1940, preceded by a 60-ton armored battleship mount in addition to a spare Mark VII 14-inch gun from the reserve for King George V-class battleships.

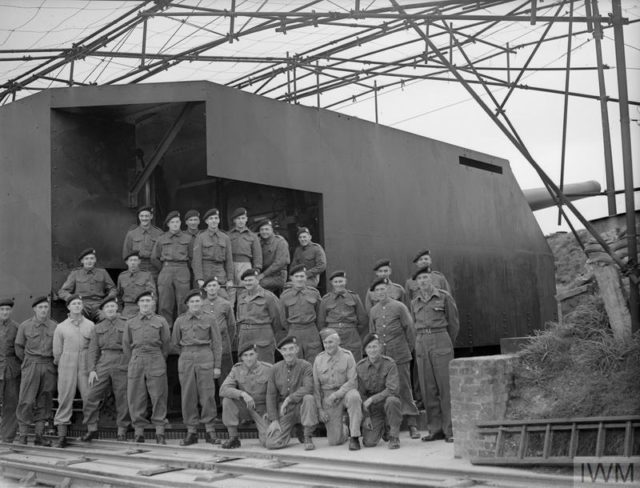

With the gun also came work crews to construct giant concrete casements to shield the guns from counter-bombardment. Those types of artillery, turreted naval guns originally designed for employment on battleship could track and fire quickly to hit moving vessels.

A new Royal Marine Siege Regiment manned the emplacement of Winnie, which was connected by a railroad tunnel to a below-ground ammunition depot, and had a separate plotting room and its own medical services.

At Cape Gris Nez, the Germans mounted four intimidating 380-millimetre SK34 naval guns of Battery Todt in large concrete casements. Nearby were four 280-millimetre guns. The Wehrmacht also delivered eight railway guns and 40 army siege guns in the Calais region. These were from 21 to 28 centimeters in caliber. But, they did not have the capability to quickly adjust fire to hit moving maritime targets.

At Cape Blanc Nez, the beach immediately west of Calais, a trio of 406-millimetre ‘Adolf Cannons’ were installed in casements protected by 13 feet of concrete. These could throw one-ton shells up to a 34-mile distance.

An additional four turreted coastal guns were mounted around Calais, and three 305-millimeter naval guns with a 32-mile range were installed near the city of Boulogne to the south.

On Aug. 12, 1940, at 11 a.m., a shell destroyed four houses in Dover. It was the first of thousands of large siege shells that would rain down in the coastal town for the next four years.

Winnie fired its initial shell on Aug. 22, 1940. Aimed at one of the German gun batteries, it caused minor damage and injured a corporal. The plentiful German guns quickly replied with a withering barrage. German records reported Winnie fired 25 shells in September that wounded a French farmer but had limited effect. Four shells fired a month later took the arm of a Luftwaffe mechanic.

Eventually, whenever one side’s guns targeted a passing ship, its opposite number would retaliate. The region around Dover and the nearby town of Folkstone became known as Hellfire Corner — the civilian residents of Dover the principal victims.

The German guns often purposefully targeted civilian areas in the town to dampen British counter-battery fire. Dover’s population dropped to half the pre-war level. The bombardments were feared more than air attacks since inbound shells could not be heard until after they had hit their targets.

Over a four-year period, German shelling killed 216 civilians and damaged in excess of 10,000 homes.

In February 1941, Winnie was joined by her less reliable-sister gun Pooh, located slightly east of St. Margaret. However, both guns were so slow to fire that they could only hit a non-moving target.

Without any form of radar targeting, the crews depended on fighter planes to spot the impact of shells and correct their aim. The heavy charges required to shoot at long range also wore out the barrels rapidly, lessening range and accuracy, and needing recurrent changes for repairs.

Bigger and more effective artillery was coming, however, including Clem and Jane, the first named after a politician and later prime minister Clement Atlee, and the second after a spicy ingénue in a Daily Mirror comic strip.

These larger, turreted 15-inch guns of the Wanstone Battery was on a reverse incline just inland of the White Cliffs of Dover, and could sustain a higher rate of fire to strike German ships.

Three First World War-era 13.5-inch railway guns named Scene Shifter, Gladiator and Piece Maker also contributed their firepower, dashing out of the Guston railway tunnel near Martin Hill station to fire their shots then dashing back inside to avoid counter-fire.

The most effective British coastal guns were four Mark IX 9.2-inch guns stationed at the South Foreland battery which became active in July 1941. These 11-metre long pieces, which depended more on camouflage than concrete for defense, had a shorter maximum distance of 21 miles, but benefited from recently installed K-Band coastal defense radars that could track and target ships.

The Fan Bay battery in the port of Dover had a moment of glory in August 1942 when its six-inch Mark VII guns sank an R-Boat, a 134-foot German minesweeper. Heavier British guns managed to scuttle to two small transports in 1943, and two bigger vessels and a torpedo boat in 1944, totaling 17,000 tons.

The German guns did not have their first victim until June 6, 1944, hitting the Lend-Lease Liberty ship SS Sambut loaded with trucks, ammunition and tanks. One hundred and thirty-six people out of 625 aboard perished.

On July 24, the German guns damaged the freighter Gurden Gates and struck the Empire Lough, killing the captain and a second crew member, forcing the vessel to ground itself in Dover.

Germany actually carried on bolstering its Calais gun batteries. Engineers began construction of a new underground fortified complex south of Calais in the village of Mimoyecques.

This was to house 25 V-3 cannons firing from behind sliding armored doors to shell the city of London 100 miles away.

Fortunately, Allied bombing seriously delayed construction, and the underground hideaway and its superweapons were never completed.

In late July 1944, U.S. troops breached the German lines in Normandy routing the Wehrmacht field army in northern France. By the start of September, the German stronghold around Calais was encircled.

Many of the Calais guns could not swivel around to fire inland, so they instead took it out on Dover, attempting to expend their remaining ammunition on the sole target within reach. On Sept. 3 a long gun duel hammered the Wanstone Battery, leaving the British guns unscathed, but leveling many of the surrounding structures.

On Sept. 25, the 3rd Canadian Infantry Division launched Operation Undergo to temper the German garrison around Calais. Though most gun batteries could not fire, they were still defended by minefields, machine gun nests and barbed wire.

The Allied troops broke the batteries’ defenses by the cover of dark, causing them to capitulate the following morning.

On Sept. 29, the 9th Canadian Brigade attacked the batteries at Cape Gris Nez. As they approached, the ill-fated coastal guns fired 50 shells on Dover in the last blaze of devastation, killing five. A 63-year-old in a shelter 38 feet below ground was the final victim of the Calais guns when a massive shell tore through a tombstone, falling on top of her.

The British guns fired with a counter bombardment greater than any that had preceded it. Finally, with the help of British spotter planes providing correction, the 15-inch Clem landed a devastating blow against the No. 2 gun at the Calais emplacement.

With the freeing of the area around Calais, the Dover coastal guns did not have much purpose. Winnie and Pooh were dismantled in October and their gun barrels deployed for use in the Pacific.

Jane and Clem had tarried into the 1950s before the British military dissolved the Coastal Artillery Branch, made obsolete by advances in missile technology, Stars and Stripes reported.

Presently, the concrete fortifications that housed the large guns around Dover and Calais are still partially intact, hardened remnants of a long-ago war.