Harvey Pratt, a member of the Arapaho and Southern Cheyenne tribes, woke up with a vision swimming around in his head. This Guthrie, Oklahoma native grabbed a writing pad and started sketching his idea, a steel circle suspended above a drum.

The surface of the drum was covered in water and an eternal flame burned in the center of the circle. The drum with its suspended ring was surrounded by a low stone wall that had four lances standing upright, one at each corner.

What made this vision so remarkable was that Pratt, a 77-year-old veteran had dreamed of the entry that he would submit to the international contest that was being run to design a National Native American Veterans Memorial.

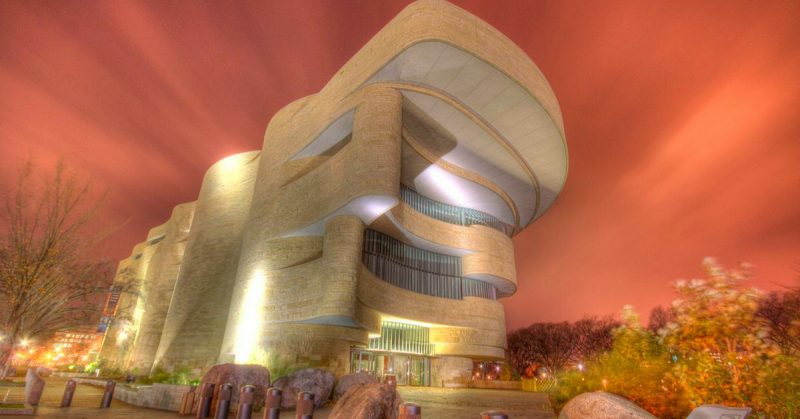

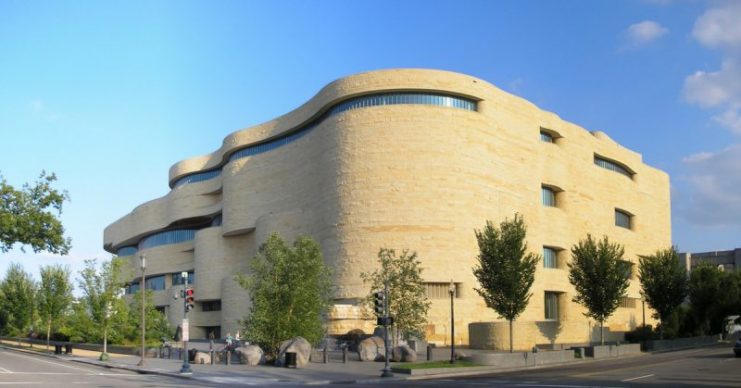

Several revisions later and after months of work, Pratt’s design was ready, and the National Museum of the American Indian’s eight-member jury unanimously voted for the design. The memorial, titled “Warrior’s Circle of Honor,” will be built in the grounds of the National Museum of the American Indian and is the first national monument to honor Native American veterans on the Mall in Washington.

There are approximately 140,000 Native American or Alaskan veterans. These veterans are drawn from the 573 federally recognized tribes, who contributed, in the 20th Century, to the military at a higher per capita rate than any other demographic group.

Harvey Pratt is an internationally recognized forensic artist and has worked for more than three decades with the Oklahoma State Bureau of Investigation. He and his family were ecstatic that his design had been selected and he told an interview with The Times that he used his background of reconstructing faces to help him translate his dream into the monument design.

In addition to his vision, Pratt relied upon his artistic and sculptural background as well as his previous experience in designing monuments. He designed the memorial commemorating the 1864 Colorado Sand Creek Massacre that stands in Denver.

![General Douglas MacArthur, commander-in-chief of the Allied forces in the South Pacific, on an inspection trip of American battlefronts, late 1943. From left: Staff Sergeant Virgil Brown (Pima), First Sergeant Virgil F. Howell (Pawnee), Staff Sergeant Alvin J. Vilcan (Chitimacha), General MacArthur, Sergeant Byron L. Tsingine (Diné [Navajo]), Sergeant Larry Dekin (Diné [Navajo]). U.S. Army Signal Corps.](https://www.warhistoryonline.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/64/2018/07/6a01156f5f4ba1970b01b7c899b25e970b-800wi-741x425.jpg)

The design had to ensure that the memorial recognized the sacrifices made by Native American soldiers, had elements of spirituality included and provided a place for people to heal.

Late in January 2018, the committee had selected the five finalists. Pratt was one of the finalists chosen and for the past few months, he and his team consisting of his wife, Gina, his son, Nathan, and Hans and Torrey Butzer of the Oklahoma-based architecture company, Butzer Architects, and Urbanism, have streamlined and tweaked the design of the monument before submitting a final proposal.

The project will start with the first sod being turned on the 21st September 2019. It has an initial budget of $8 million and is due for completion in late 2020. The judging panel noted that the design met every one of their directives and they described Pratt’s design as “culturally resolute and spiritually engaging.” Special mention was made of the central steel ring saying that it is “a universal and inclusive” symbol.

Pratt described the use of the ring, the drum, the eternal flame and the water as his means of ensuring the monument was representative of all Native American veterans, from Alaskan Natives through all the Native American peoples, from mainland USA through to the Hawaiian natives.

These attributes are common to all ancient cultures and are used in all Native American ceremonies. The metal ring is intended to represent time and its infinity and transcends all tribal affiliations.

In his interview, Pratt said, “Indian people saw the circle in the sun and the moon, and they saw it in the weather, and they saw it in the seasons and the cycle of life. The warrior’s circle of honor is timeless — it will be there 100 years from now, and it would mean the same thing.”

In discussing the designs submitted the committee agreed that the project was a daunting task at the beginning. Trying to honor all tribes at one time seemed an impossible task, but the committee agreed that Pratt had done a fantastic job of bringing all the significant elements together in a pleasing and culturally sensitive design.

One of the committee members, Allen Hoe, a veteran of Native Hawaiian descent, was very complimentary about the design saying,

“Some of the other submissions tended to try and define one element of native culture, either the dance, the headgear, et cetera, and it seemed to be inadequate [because] there’s something different in all of the native cultures.” But I think Pratt’s circle of honor was able to pull all of that together and just go back to the basics.”

Not only will visitors be able to admire the beauty of the monument and sit in quiet reflection, but they will also be able to become part of the memorial. Many Native American people will tie a small ‘prayer cloth’ onto tree branches.

This little cloth is dedicated to a specific person and is imbued with the spirit of the prayer. When the wind blows the little cloth flutters and carries the prayer to that person. Pratt is hoping that visitors will tie their prayer cloths to the four lances at the corners of the monument and allow the wind in Washington to send the prayers.

Allen Hoe’s son, Nainoa, was a casualty of the war in Iraq and was killed in 2005. Hoe said that he will attend the dedication service for the memorial and will bring with him a Hawaiian prayer cloth, called a “kapa,” made from the bark of the mulberry tree. His kapa will be presented as representative of the culture of his people on the islands and will be tied to one of the lances.