Although movies like to portray intense cat and mouse submarine battles that are fought solely underwater, this type of combat is actually extremely rare. So rare, in fact, that only a single submarine has been sunk while both it and the attacker were submerged. This occurred right at the end of WWII, in a duel between a British submarine and a German U-boat, suspected of transporting top-secret goods to Japan.

Prelude

It may seem like submarine duels taking place underwater were rather commonplace, but this type of engagement is actually extraordinarily complex. This is partly why the sinking of U-864 is so significant.

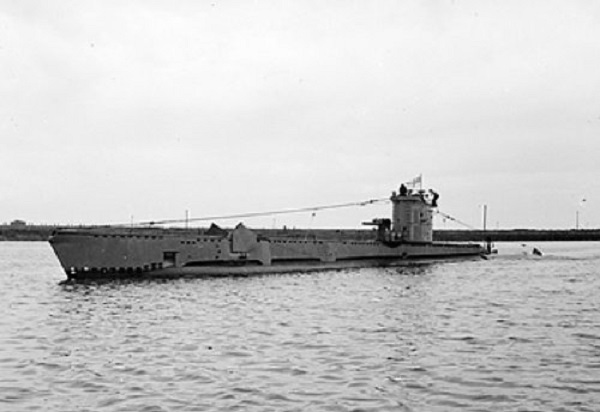

It happened in February 1945, just months before the war in Europe formally ended. The duel was between two submarines, the Royal Navy

and U-864 of the Kriegsmarine.

Venturer was a British V-class submarine that launched in May 1943. She was 206 ft long, displaced 740 tons submerged, and was armed with four 533 mm torpedo tubes. On the surface, her diesel-electric propulsion enabled a maximum speed of 13 mph. While submerged she was still capable of 12 mph.

She was an attack submarine, which would find a target, destroy it and make a quick getaway without a prolonged battle.

The V-class was a successful submarine design, but HMS Venturer had a particular advantage; its captain, Jimmy Launders. Launders was an extremely capable captain who was well respected by his crew. He had a great intellect and a penchant for mathematics, which was useful in submarine warfare for crunching the complex calculations involved with establishing a target’s distance, speed, and direction of travel.

Although his posting on the Venturer was his first in a submarine, he quickly proved to be a great commander of both his crew and the machine. Before the encounter with U-864, Venturer, under Launders’ command, had already sunk four vessels, including a German submarine.

One of his crew members said of Launders:

“We trusted him. We knew he was a good commander. We’d have gone to the end of the Earth with him…because he was that good.”

On the opposing side was U-864, a 290 ft, 1,800-ton beast that was designed for long-range ocean-crossing operations. She was commanded by Ralf-Reimar Wolfram. In December 1944 she left Kiel, Germany, as part of Operation Ceaser; Germany’s secret mission to send supplies to Japan to help their increasingly desperate situation.

She was carrying 65 tons of mercury and a number of plans, parts, and specialists involved in the manufacture of jet aircraft. After leaving Kiel, she experienced issues with her snorkel and ran aground, so she headed to Bergen for repairs. After these were complete, she left for Japan. However once again problems struck, likely relating to an engine misfire. This loud thumping noise would be easily detected by hydrophones, so she was ordered to return to Bergan for more repairs.

Unknown to the Germans, their coded naval communications had been cracked by the Allies, who knew about U-864’s top-secret mission and her rough location. The Royal Navy dispatched HMS Venturer to find and sink U-864.

The sinking of U-864

The Venturer was sent to U-864’s estimated location but didn’t know of U-864’s latest mechanical issues. Unfortunately for U-864, her return voyage to Bergan would bring her back towards the Venturer. When Venturer entered this area, Launders made the risky decision of switching off their sonar. Sonar was used to accurately locate vessels, but it could be detected by the enemy too.

Instead, Venturer would rely on its hydrophone, a much older and more crude technology that essentially lets an operator listen to noises outside the submarine. Her hydrophone operator heard a strange noise that he first thought was the engine of a civilian boat. However, the noise he could hear was the sound of U-864’s rough-running engine.

Venturer closed in on the noise and spotted a submarine snorkel poking out of the water. Realizing it was indeed a submarine, Venturer followed quietly behind to wait for it to surface. Incredibly, Launders followed U-864 using only the hydrophone, an immensely difficult task.

U-864 discovered that they were being followed and began zig-zagging through the ocean. Knowing the enemy wouldn’t surface, Launders decided to try to sink the submarine while it was submerged and zig-zagging.

At the time this was a virtually impossible shot. Without being able to visually see the target, it would be extremely hard to know its distance, speed and direction, made even worse by the evasive maneuverers. The calculations involved with such a shot are simply mind-boggling, but Launders and his crew were able to do it.

Predicting U-864’s future movements, Launders ordered the firing of four torpedoes. U-864 detected the incoming torpedoes and managed to avoid the first three, but in doing this, she steered directly into the fourth.

U-864 sunk quickly, claiming all 73 on board. She landed on the sea bed 150 below the surface, and wouldn’t be discovered until 2003.

Venturer and her crew continued in service until the end of WWII. After the war, she was sold to Norway, where she was known as HNoMS Utstein. She was scrapped in 1964.

Today, the wreck of U-864 poses a serious environmental hazard due to the 65 tons of mercury still contained within her hull. The Norwegian government plans to entomb the wreck with sand and rocks to prevent further contamination. Conservative MP Ove Trellevik told Express: “This is an environmental bomb that sooner or later will have major consequences for society.”

Slowly, the mercury’s steel containers are corroding, leaking mercury into the surrounding water.