It was exactly 4:00 AM on November 27, 1942. A thick veil of darkness was lingering over the skies of Toulon, but the city’s inhabitants were stripped of sleep as Nazi Germany’s forces swarmed through it in large numbers, brimming with bad intentions.

This particular force, comprising elements of the 7th Panzer Division and supported by units from other divisions, had been deployed by Hitler to capture all military assets belonging to Vichy France. At the core of this invasion was the plan to capture the French fleet which contained some of the most sophisticated warships of the time.

It is important to know that France had been in the hands of Germany following the latter’s invasion of France and the Netherlands in 1940. Officials of Nazi Germany and France had signed an armistice on June 22, 1940 at Compiègne, officially acknowledging German authority over France and putting an end to hostilities.

By the end of June 1940, Nazi Germany settled into the north and west coasts of France, while the colluding Fascist Italy took hold of a small portion of the southeast zone, leaving the southern part of France to the new French Vichy regime. The southern part was called the Free Zone, with its capital situated at Vichy.

According to the armistice, the French fleet was to be retained under French control within Vichy France. But this fleet was to remain disarmed and never sail away from its harbor. Also, the port city itself was to serve as a stronghold and put up fierce resistance against any onslaught from the Allies.

The Allies believed that Vichy France was only a puppet state and feared that Germany would soon take over the French fleet. If this should happen, it would pose a major threat to the British who controlled regions in North Africa not far away from southern France.

Indeed, the officials of Vichy France were not keen on letting the Germans get hold of their ships. But the Allies needed more than mere resolve. A number of meetings with Vichy French Naval commanders ensued, with the British trying to persuade the Vichy French officials in North Africa to break the armistice and send their fleet to the Allies.

These meetings did not quite go in the Brits’ favor, though, so in order to eliminate the high risk of German seizure of the French fleet, the British launched Operation Catapult, seizing a number of French ships and destroying a few.

The leader of Vichy France, Marshall Petain, angry and still not willing to break the armistice, then cut off all communications with Great Britain.

Operation Torch would be launched in 1942, with Allied forces storming into French North Africa. Immediately following the invasion of French North Africa by the Allies, Hitler quickly launched Operation Anton—the invasion of Vichy France.

By launching an attack on Vichy France, Nazi Germany clearly violated the armistice. But this was proven to have been Hitler’s intention from the outset. He intended to forcefully take over the port city of Toulon and the French fleet.

Upon this dishonorable act by Nazi Germany, the true colors of the Vichy French were revealed: all they had for Germany was resentment, and they would rather sink their ships than let the Germans take them.

Hitler’s move had been rather expected by some officials, like Vichy Secretary of the Navy Admiral Gabriel Auphan. Prior to his resignation, Auphan ordered his subordinates to oppose the invasion of foreign troops and to scuttle the ships if any foreign intruders should force their way through to the fleet.

Thus the drama began that early morning of November 27, with a swift force of armored vehicles and motorcycles storming the town of Toulon and rapidly taking over major arsenals and coastal outposts in the east and west regions of the port.

By 4:30 AM, they broke into Fort Lamalgue, arresting Admiral Marquis. However, the Germans were unable to prevent Marquis’ chief-of-staff from radioing the order to scuttle the entire fleet.

On hearing the news, Admiral Laborde was astounded by the swiftness of the attack, which he had not quite expected. But he reacted with a swiftness of his own, giving orders for the scuttling of the ships to get underway.

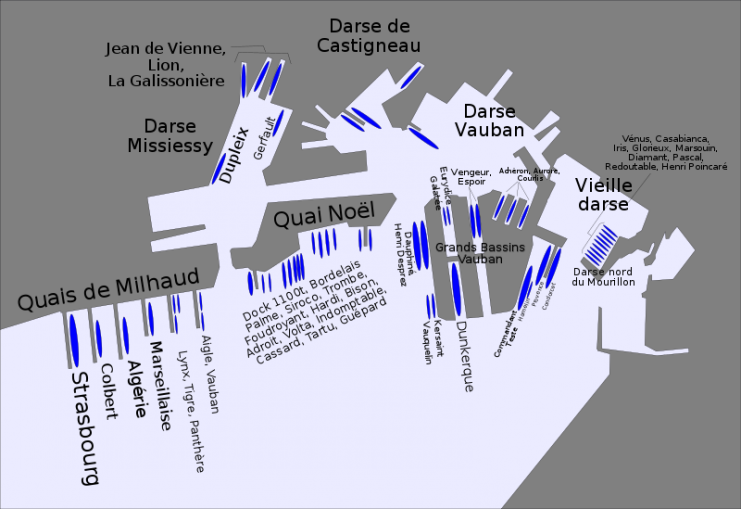

Owing to the fact that the harbor area was a maze of several naval infrastructures, the German main force lost its way while cutting through the arsenal. By the time they located the main gate to the base, they were one hour behind schedule.

There at the gate, they demanded entrance into the base. But they were about to experience an annoying old school delay tactic: the French guard at the gate made a friendly request for access paperwork.

This sparked a debate between the French sentry and a baffled German officer who insisted he didn’t need any paperwork to go through the gate. After the guard delayed them for as long as he could without a fight, at 5:25 AM the German tanks began to roll through the gates.

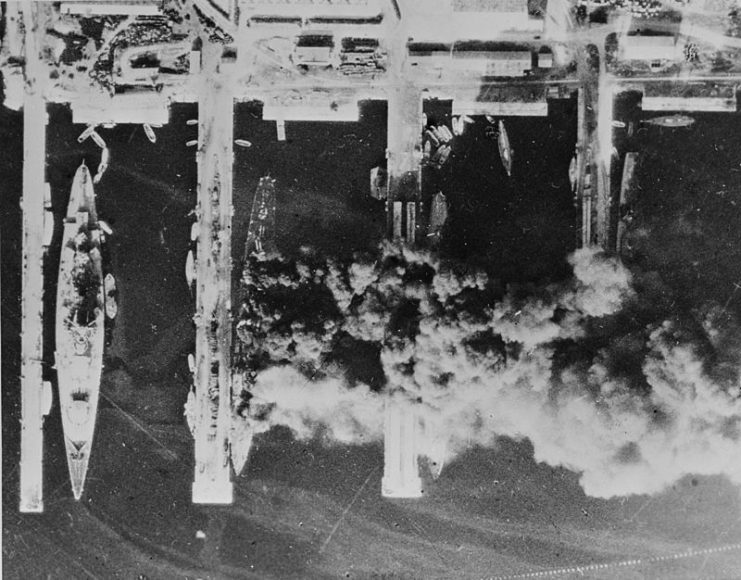

By then, the scuttling parties had gone far in their duties, setting up demolition charges and opening the sea valves on all ships.

Explosions echoed through the air as bright flares punctuated the pale morning skies. German troops scurried toward the ships which were now destined to go beneath the sea’s surface. Fighting ensued between German troops and the French sailors as thick smoke and raging fire persisted in the background.

The hostile engagement would result in twelve French servicemen dead and twenty-six injured. Only one soldier died on the German side.

The Germans attempted to salvage as many of the sinking ships as possible, but the French were determined to see their ships drown. One by one, cruisers, battleships, torpedo boats, sloops and submarines went to the bottom of the bay.

The operation ended with the destruction of seventy-seven vessels by the French sailors. Some of the ships burned for many days, polluting the harbor with oil so badly that for two years it was impossible to swim there.