People often don’t stop and consider the decision-making process that went into the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki during World War II. Malcolm Gladwell’s book, The Bomber Mafia: A Dream, a Temptation, and the Longest Night of the Second World War, examines the arguments put forward by Brig. Gen. Haywood Hansell and Maj. Gen. Curtis LeMay on the best way to bomb the country during the conflict.

Establishing the ‘Bomber Mafia’

The Bomber Mafia originated from the slaughter of the First World War. In the immediate aftermath of the conflict, US Army leadership expected the Air Corps Tactical School (ACTS) at Langley Field, Virginia to produce men trained to use airpower to support ground troops.

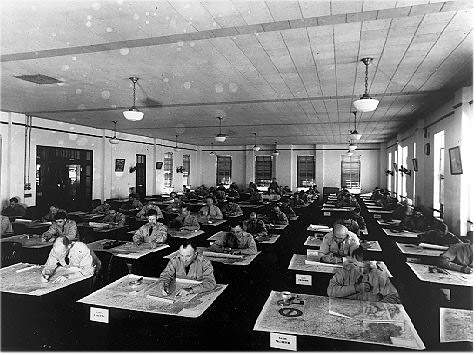

However, rather than use airpower as a secondary strategy, airmen training at the ACTS came together to develop a new idea with a focus on using the method as a primary wartime weapon. Their concept was a new bombing strategy that could utilize aircraft as a new type of war arm.

They developed a doctrine that envisioned strategic bombing to paralyze an enemy’s industrial infrastructure, which would, in turn, eliminate their war-making capacity.

Facing opposition within the US military

When this doctrine was developed, it faced a great deal of opposition within the US military. In fact, the eventual nickname of “Bomber Mafia” came from the bitter debate between Army staff and the Air Corps (USAAC), who felt a separate air arm was required to command them.

In the early interwar period, senior Army leadership still thought of aviation in terms of observation and attack, rather than pursuit and bombing. Any attempts to express the school’s views and ideas were quickly shot down by the General Staff.

Money posed yet another problem. At the time, the military’s budget was very limited, and neither the Army nor the US Navy was willing to give up the limited sum they were allotted. It was easier for both to regard the Air Service as just another Army combat arm, rather than as an independent and equal service.

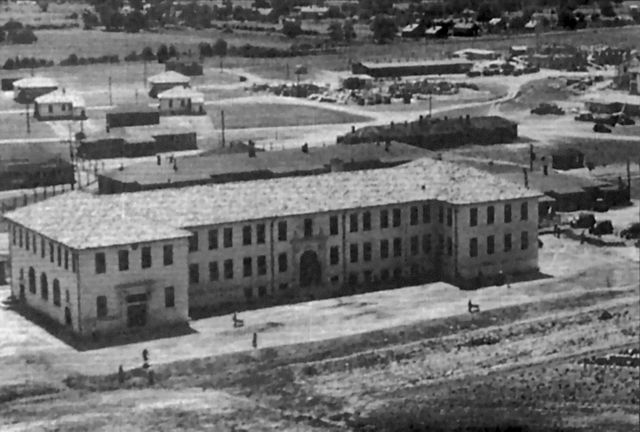

Nonetheless, the ACTS, which changed its name to the Air Service Tactical School (ASTS) in 1922, continued to investigate ways in which airpower might influence future combat. In 1931, the school moved from Langley to Maxwell Field, near Montgomery, Alabama. It was there that the “Bomber Mafia” was truly born.

Emergence of the ‘Bomber Mafia’

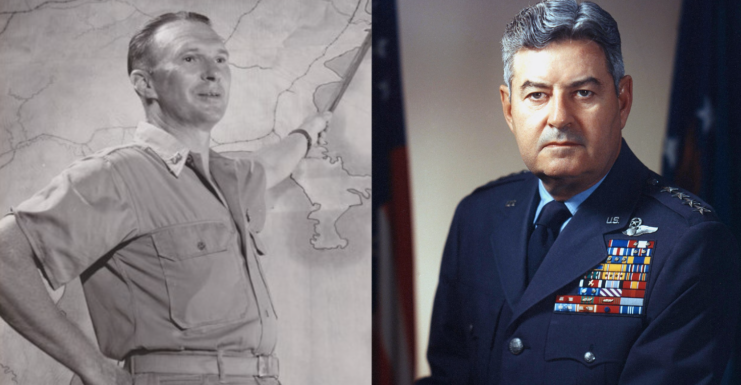

By the time the Air Service Tactical School moved to Maxwell Field, the idea of supremacy in airpower had become the official goal of the vast majority of staff and students. There grew to be a small circle of men who came to represent these ideals and would be known to history as the primary figures involved in the Bomber Mafia. They included the likes of Lt. Gen. Harold Lee George, Haywood Hansell, Maj. Gen. Robert Olds and Curtis LeMay.

The Bomber Mafia believed airpower would become the deciding factor in future wars and that it shouldn’t be just a new weapon, but also a new service in the US military, equal to the Army and the Navy. Their goal was to create a long-range air force with the capability to attack and defeat an enemy by bombing military industries in its homeland. In doing so, the Bomber Mafia reasoned, conflicts wouldn’t only be shorter, but could also eliminate the loss of human life.

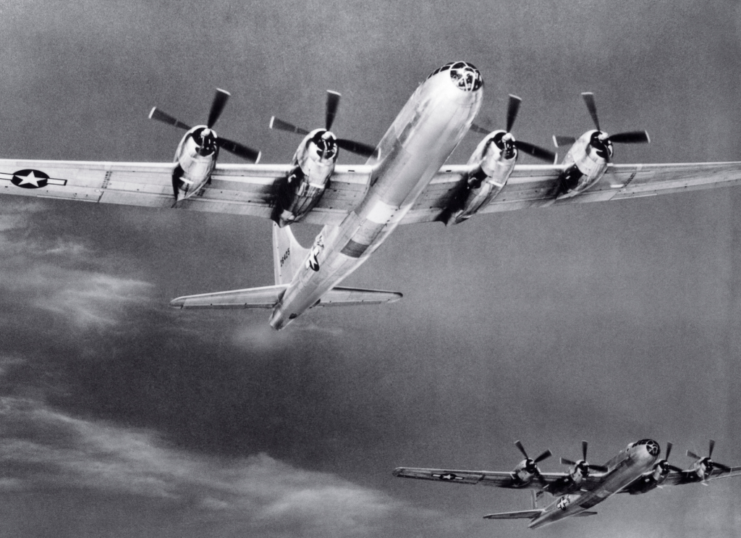

Of course, the next step for implementing this doctrine was to establish a large fleet of heavy bombers, meaning the government would have to reduce its funding to naval and ground forces. By 1935, the Bomber Mafia had made great strides in acquiring the necessary aircraft and were able to test their doctrine, which now centered around the high-altitude, daylight, precision bombing of enemy infrastructure.

The Bomber Mafia’s strategy was tested, although only in optimal conditions, and by the beginning of the Second World War, their doctrine had become the primary airpower strategy for the United States.

Curtis LeMay versus Haywood Hansell

Haywood Hansell was a junior member of the Bomber Mafia who rose through the ranks throughout World War II. In August 1944, it was announced he would command the XXI Bomber Command, based in Saipan. These airmen were the ones charged with conducting air raids on industrial sections of Tokyo.

Hansell was a big believer in the Norden bombsight, a technical innovation that would allow forces to focus on hitting specific targets. The device worked, but only in ideal weather conditions. While a solid idea, it didn’t pan out in practice; the technology didn’t yet exist to do the additional computations that real-world issues required.

Strategic bombing raids in Japan were largely unsuccessful under Hansell’s command, as they caused little damage to Japan’s wartime and military industries. At the end of 1944, he was replaced by rival Curtis LeMay. LeMay was a believer in napalm, a bombing tool in the form of a burning gel that was designed to inflict maximum damage to Japanese homes.

Rather than focus on the strategic bombing of Japanese industrial complexes, LeMay began a campaign against civilians, using strategic bombing and dropping napalm on 66 Japanese cities.

LeMay was responsible for the bombing of Tokyo on March 9-10, 1944. More than 2,000 tons of firebombs were dropped, and it’s estimated that up to 330,000 people were killed. The US Strategic Bombing Survey estimated more civilians had lost their lives by fire in Tokyo in six hours than at any other time in history.

Reflecting on the attack, veteran Jim Marich recalled “hating what they were doing,” but “thinking we had to do it. We thought that raid might cause the Japanese to surrender.”

Proving the Bomber Mafia’s doctrine wrong

Ultimately, the Bomber Mafia’s theory of the primacy of unescorted daylight strategic bombing was proved wrong. Fleets of heavy bombers couldn’t achieve ultimate victory without to assistance of the US Army and Navy.

Their doctrine was further proved wrong as victory in the war didn’t come any quicker and wartime casualties were not minimal, especially thanks to the actions of Curtis LeMay.

Years after the firebombing of Tokyo, LeMay stated, “Killing Japanese didn’t bother me very much at that time… I suppose if I had lost the war, I would have been tried as a war criminal… every soldier thinks something of the moral aspects of what he is doing. But all war is immoral and if you let that bother you, you are not a good soldier.”

More from us: Was the Allied Bombing of Dresden a War Crime or Wartime Necessity?

These attacks on Japanese civilians by the Bomber Mafia may have aided in hastening a victory for the Allies. However, the question remains: Victory, but at what cost?