The news of Hitler’s demise spread like wildfire throughout Europe, and by May 1, 1945 most of the people directly involved in the combats on both sides knew that ‘Fuhrer’ is no more. For some, the war had ended with Hitler, however for others the struggle continued even after the end.

British people took to the streets to rejoice the end of the bloodiest era of modern history. Strangers danced arms in arms celebrating the VE (Victoria in Europe) day. Nearly 5 million British troops breathed a sigh relief and prepared to go back to their homes.

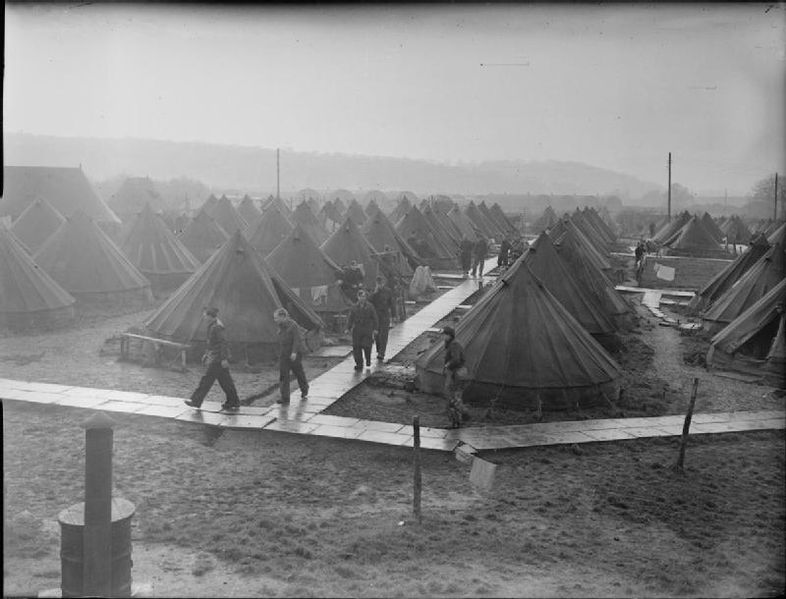

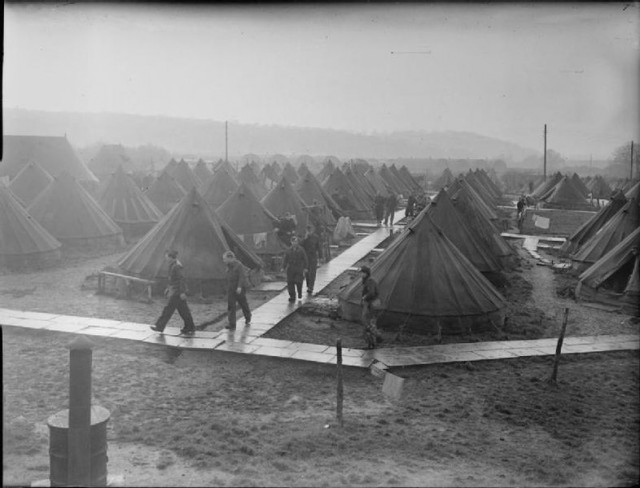

The situation was a little different with almost 180,000 German prisoners of war kept in 1000 British camps up and down the country. Though most of the prisoners were glad at the prospect of going back to their homes after the war, while others feared a ruthless reaction from their captors. On May 8, 1946 POWs were ordered to gather in their prisons, and they were told that the war in Europe had officially ended and that Hitler was dead. There was a general sense of relief among many prisoners as they thought they could go home now, but it was too early to think that.

The news started arriving that British POWs were getting freed very quickly as the Allied forces swept through previously Nazi run territories. But there were no signs or indication from British authorities for the release of German prisoners. There were rumors that Britain is planning a prolonged imprisonment of German’s prisoners, especially the Waffle-SS could stay in the camps for as long as 25 years.

The news of Nazi concentration camps increased the fear among German POWs. There was a sense of disgust throughout Europe after the footages of the camps were shown in public cinemas. German prisoners were ‘forced’ to watch the footage in special makeshift screens. Though some of the prisoners took this as propaganda by the Allies, however many were convinced that Nazis were very much capable of such atrocities. But the fierce public reactions added to growing paranoia among German prisoners.

The events that followed the screening of the camp’s footage did not help easing the fears of the prisoners. They were forced to work long hours, with very less supply of food and drinks. Britain blamed the measures on the shortage of food and other basic things due to the War. However, German prisoners were certain that they were going to face the British wrath as a reaction to concentration camp’s atrocities by Nazis.

Even during the War growing numbers of German POWs were put to work on various projects. Most important and the hardest task was the work on farms, as Britain was facing acute shortage of supplies from outside. Other prisoners were made to demolish the buildings destroyed by German bombings. The prisoners were getting less then a shilling a day, which could only buy them 4 cigarettes inside the prison. But they did not complain; as working hard on farms was far better then a bullet to head. The situation did not change a great deal for prisoners even after the War had ended. Britain did not seem particularly interested in quick repatriation of German prisoners.

But slowly situation seemed less gloomy and hopeless for the prisoners, when British government eased down the prison regulations. This brought huge sigh of relief for the prisoners. British public, especially the farm owners showed no particular hatred towards the prisoners. Even some prisoners started befriending with the people they were working for.

British government, though lenient, did not seem interested in sending the prisoners back home. There were 260,000 POWs up and down the country and another 130,000 arrived from the US. The number of German prisoners swelled to almost 400,000. Apparently British authorities saw an opportunity to use these prisoners to help rebuilt the war torn country.

Very soon public concerns started increasing over this apparently ‘forced labor’ policy of the British government. British authorities introduced even more facilities for the prisoners. They were allowed to visit British members of public. There was no shortage of food or clothing for prisoners any more. They were even provided with books and film shows for their entertainment. Special educational programs were introduced to educate the prisoners of the democratic values of the ‘new’ Europe, The Independent reports.

When German prisoners were having a rather pleasant time under their British captors, in 1947 Britain was hit by a catastrophic weather conditions. Prisoners worked with British troops shoulder to shoulder on the roads and rail networks to clear the snow, which kept the wheel of economy rolling.

According to an Academic JA Hellen, there are various dimensions of the German POWs in Britain. They contributed a fair bit in rebuilding the post-WWII Britain and their relationships with British members of public help counter any prevailing hatred among the people of Europe, and a much broader understanding of a friendly Europe emerged.

Britain started the repatriation of the prisoners in September 1946 and finished the process by 1948. But Britain decided to keep 25,000 of prisoners, but not as prisoners but as members of the public. Many among these 25,000 married British women and had started a family in Britain. Some of those 25,000 veterans are still alive in Britain.