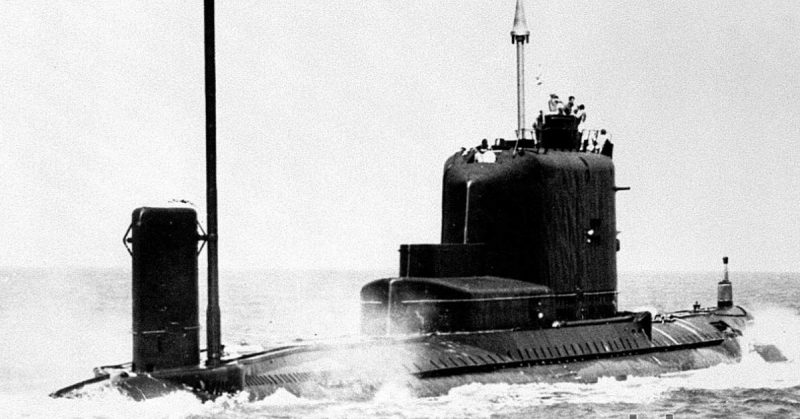

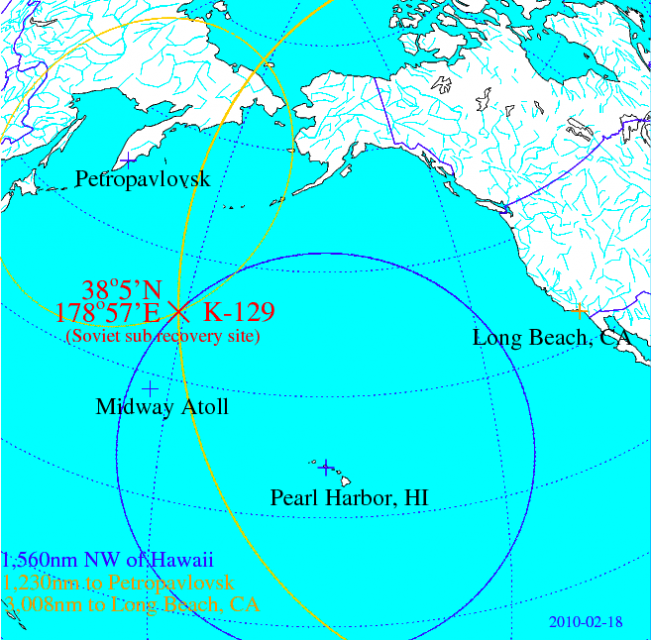

The story is straight out of a Cold War techno-thriller. It’s February 1968, and the Soviet submarine K-129 has disappeared while conducting its ordinary patrols in the Pacific Ocean. The Soviets conducted a massive search, using all of their air, sea and submarine resources, but by March they officially declared the K-129 and its crew lost.

The submarine was loaded with a Soviet nuclear missile, and the United States intelligence and military communities saw the chance to recover not just an enemy submarine but also a nuclear warhead as an opportunity they could not pass up. Thus, Project Azorian was born.

This project would be among the most expensive and top secret operations of the Cold War. However, for all the time, money and manpower put into it, the operation only achieved modest levels of success.

Given the marvels of engineering and duplicity required for the United States to ascertain the sub’s location, construct a rig to retrieve it, and then develop a cover story to sell to the media to explain their actions, the mission ended up only finding part of the submarine, and only some of the secrets that the American spies had hoped to acquire.

Josh Dean, the author of the new book The Taking of K-129, explains how it was done. First, the project leaders didn’t call in the services of the U.S. Navy to raise the boat from three miles below sea level. Instead, it called in the Central Intelligence Agency.

And why not? Dean suggests that it made it easier to keep Project Azorian a secret, and the CIA had proven themselves to be quite capable in terms of succeeding at somewhat unorthodox operations. It was CIA engineers after all who developed the U-2 and the SR-71, high-altitude spy-planes used to gather intelligence on the Soviets in an attempt to close the “intelligence gap.”

One of the biggest problems with the requirements was that the United States had never recovered anything particularly big from more than a thousand feet down, and that meant that the CIA would have to improvise.

First, everything on the Hughes Glomar Explorer, the ship involved in the operation, had to be designed and original. There would be no off-the-shelf equipment at work during this operation. That meant camera systems, sonar and hydraulics would need to be specially designed for this operation.

The government turned to the best optics people in the United States to determine how to image that deep underwater without producing the distortions or shadows that would undermine the effort. Even the claw that would be used to draw the wreck from the deep had to be designed with the specifications of the wreck in mind.

Then there was the public perception and secrecy to be managed and maintained. This type of operation would never be possible today with camera-phone footage and instant uploads to social media, not to mention boards like Reddit and YouTube, but communication and surveillance a half a century ago lacked today’s sophistication.

Still, the United States government would require an explanation and a cover story for their salvage ship operation before they took it out into the middle of the ocean.

So the United States enlisted reclusive, eccentric millionaire Howard Hughes, who told the world that he was going to be using the Hughes Glomar Explorer to mine manganese nodules from the sea bottom.

Naturally, the public believed every word of it. In the process of research for the novel, Dean collected stacks of media clips from the 1970’s, which included the efforts of people reporting on Hughes undersea mining exploits. The lie was so convincing that the United Nations were prompted to discuss the legality of Hughes exploits.

The misinformation campaign lasted for almost forty years. A New York Times reporter heard some curious details in 1974, but was intercepted by government officials who asked him not to print his findings to protect national security secrets.

Then in 1975, a story about the salvage operation ran in the L.A. Times prompting the New York Times reporter to print his findings. Regardless, Project Azorian retained its fully classified status until the CIA released a redacted history in 2010.