A waterfall of blood-red ceramic poppies will tumble down the walls of St. Magnus Cathedral in Kirkwall for the period of April 22, 2016, to June 12, 2016. This stunning display originally graced the Tower of London and was commissioned to honor the death of every British and Colonial man who died in World War I between 1914 and 1918.

But in Scotland, it will also be used commemorate the Battle of Jutland, which took place off the coast of Denmark in the North Sea and started on the 31st of May in 1916.

This Battle of Jutland was the one and only major sea battle of World War I, and while both sides claimed victory it took the lives of over 8,000 men. It was also the one and only battle fought between the so-called “dreadnoughts”. In 1906, a new type of battleship, the HMS Dreadnought, was launched. It made a huge impression on people, and all battleships of a similar type were called dreadnoughts.

The launch of this vessel with its heavy-caliber guns, steam propulsion, and heavy armor launched Britain and Germany into an arms race that saw both navies with dreadnoughts at the start of World War I.

At the start of the war the British public had an unfailing faith in the supremacy of the British fleet; after all, they had ruled the waves for a century or more and the expectation of the British public was that any sea battle would be won by the British.

The fleet had been involved in a couple of small skirmishes with the German fleet, but the feeling at the time was that any major sea battle may leave the losing country vulnerable to attack, so the fleets seemed to avoid each other.

At the outset, the British did not believe that the German Navy would sail through the Channel as they would be forced to face the might of the British Navy stationed at Portsmouth and Plymouth. The British believed that the Germans would restrict their activities to the North Sea, so the Navy stationed ships at Rosyth, Cromarty, and Scapa Flow, intending to keep the German fleet pinned to the North Sea and preventing them from getting to the Atlantic. The goal of this positioning was to keep Germany from stalking the British Merchant fleet and causing Britain problems with importing supplies.

In line with this thinking, the British fleet had blockaded Germany’s northern coast; by 1916 this blockade was proving very effective, and Germany was suffering as a result. At this time, the German High Seas Fleet was commanded by Admiral von Poul. But his handling of the blockade was criticized, and he was replaced, in 1916, by the hawkish Admiral Reinhold von Scheer.

Von Scheer’s strategy was to lure the British fleet out of their ports and, using both underwater and surface vessels, destroy them one at a time. He launched a series of raids on the coastal ports of Lowestoft and Yarmouth on the evenings of the 24th and 25th of April, 1916 in the hopes that this would draw the British Navy out. Von Scheer was of the opinion that his codes were safe and that the British could not understand his coded messages, but this perception was incorrect, the British were well aware of his planning.

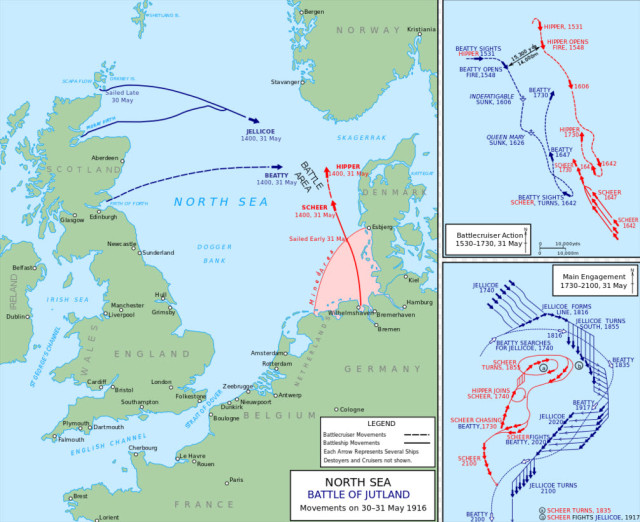

Von Scheer sailed with the entire High Seas Fleet and, as he thought his messages were secret, he did not expect the Grand Fleet of the British Navy, based at Scapa Flow, to sail. But they did; the British Grand Fleet sailed with 37 heavy units and 113 light units, compared to the 27 heavy units and 72 light units attached to the German High Seas fleet.

Both fleets were sailing in a roughly similar pattern with light cruisers scouting ahead of the main fleet since the spotter aircraft of the time could not cover the vast distances in the North Sea.

The two scouting forces met off the coast of Jutland, and a running artillery duel commenced. The British forces under the command of Rear Admiral Beatty pounded the German cruisers, but those had been built with heavier armour in the hull and, as a result, they were able to withstand the battering that they were given.

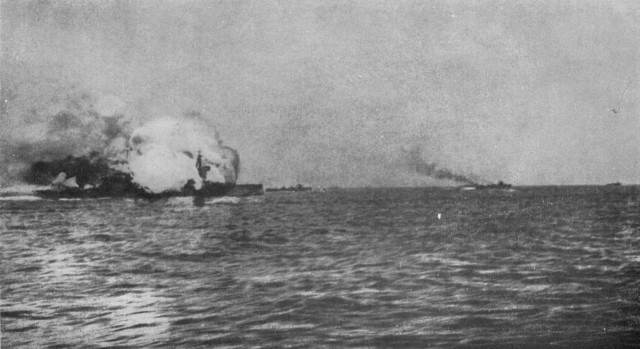

The British lost three cruisers, mainly because they had no anti-slash protection in the gun turrets, so fires started from incoming shells quickly reached the powder rooms and caused explosions. The British fleet lost the HMS Indefatigable with a thousand men perishing when the magazine blew up. Then the Queen Mary sank in just 90 seconds and lastly, the HMS Invincible sank just after 6:30 pm.

Beatty peeled off, and the Germans chased him with their dreadnoughts, north right down the throat of the British Grand Fleet. At this stage, both admirals were convinced that the battle was being played out according to their plans. These two fleets represented an awesome amount of firepower, and the British heavy guns pounded on the German fleet, forcing Von Scheer to order a retreat.

Jellicoe refused to follow, believing that this was meant to trap the British into a submarine attack. He slowed, and when von Scheer turned, hoping to pass behind Jellico, he ran straight into the British bombardment again. The German fleet found themselves passing in front of Jellicoe’s ships, which had been wheeled to port and were in a straight line.

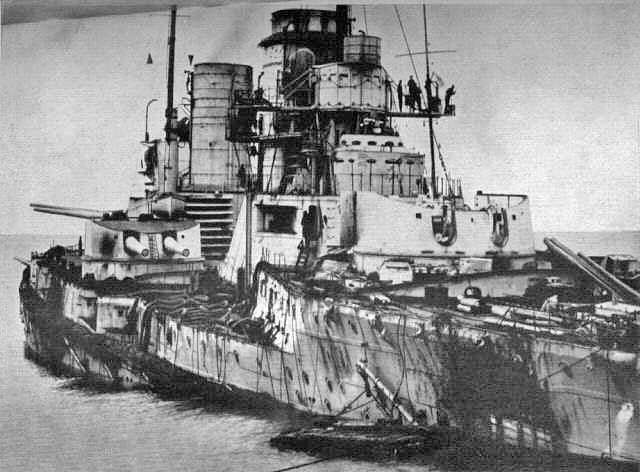

Von Scheer’s fleet landed two hits as compared to the 27 landed by the British. The Germans escaped after executing three battle turns, protected by their lighter cruisers. Jellicoe was hampered by fears of torpedo attacks and did not follow the Germans as speedily as possible.

In the end, the Germans lost nine ships and had 2,500 casualties while the British lost 14 ships and had over 6,000 casualties. The Kaiser decorated most of the participants of this battle, and the Germans considered it a win, but the German fleet had taken a serious pounding, and the fleet was not able to take to the seas again. The German navy took to raiding the British Merchant Fleet using U-Boats.

Admiral Jellico was full of praise for the bravery of his fleet on that day and wrote in his report “The conduct of officers and men throughout the day and night actions was entirely beyond praise. No words of mine could do them justice. On all sides, it is reported to me that the glorious traditions of the past were most worthily upheld – whether in heavy ships, cruisers, light cruisers, or destroyers, the same admirable spirit prevailed.

Officers and men were cool and determined, with a cheeriness that would have carried them through anything. The heroism of the wounded was the admiration of all. I cannot adequately express the pride with which the spirit of the Fleet filled me.”

This major battle involved neither submarines nor aircraft and assured the British Navy it was invincible for the duration of the war. The poppy sculpture that will rain down the walls of the cathedral will be a fitting memorial to not only the 6,000 British casualties of that day but also the thousands of young men that lost their lives during the course of the war.

By Grandiose – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, $3