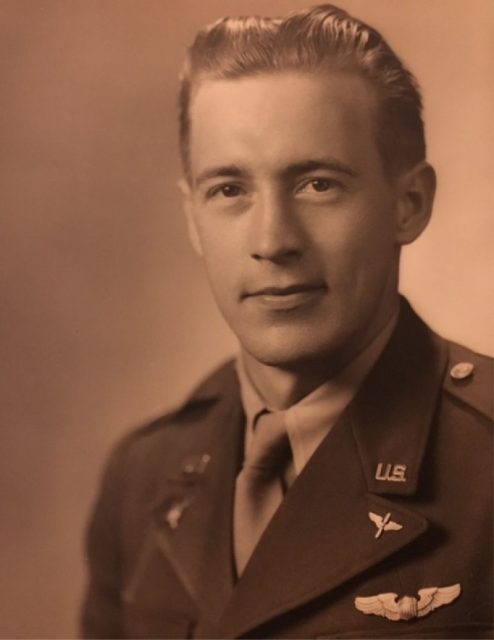

On July 14, after approximately 75 years, a World War II army pilot’s remains were at long last sent home for a proper burial in his hometown of Harrisburg, Virginia. Because of the efforts of the DefensePOW/MIA (Prisoners of War/Missing In Action) Accounting Agency, (DPAA), First Lieutenant William Shank has been laid to rest among family and friends in Harrisburg.

It was a long time coming, but the DPAA’s efforts, combined with scientific research and advances like DNA testing, has ensured that First Lieutenant William Shank is now buried at home. Previously, he was simply listed as an “unknown” in the Ardennes American Cemetery in Neuville-en-Condroz, Belgium.

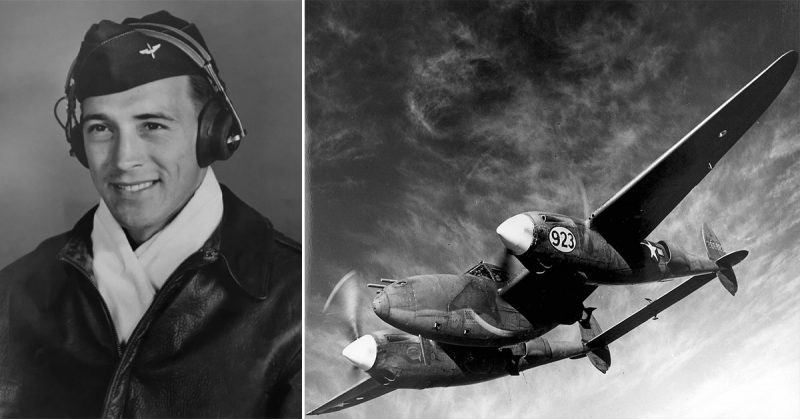

Shank, who was awarded the Air Medal and the Purple Heart, was escorting B-17 bombers on their to Bremen, Germany, when his plane went down near Osteresson. While his partial remains were found in 1948, it is only because of progress in pathology and science made during the last several decades that scientists were able to find out who the First Lieutenant actually was and ensure he made it home to rest near family and friends.

First Lieutenant Shank was a pilot with the 338th Fighter Squadron, 55th Fighter Group, 66th Fighter Wing, 8th Fighter Command, 8th Air Force. He was on a mission to Bremen, Germany, when his plane was shot down. And while his partial remains were found in 1948, the science of the day simply did not allow for a proper identification of the body. It was in 1948 that the American Graves Registration Command moved the remains from Germany to its official cemetery in Belgium.

Many decades later, in 2008, Werner Oeltjebruns, a German researcher told American officials that he could help unearth any secrets held by the crash site and that those secrets should be excavated. Representatives of the Joint POW/MIA Action Command, at the Department of Defense’s POW/MIA was once called, met with Oeltjebruns to learn how he could help.

The DPAA agreed that the case warranted further exploration. In 2016, it sent a team of researchers, historians, and a medical examiner to meet with Oeltjebruns, and they collectively headed to the crash site at Osteresson. Fortunately, there was indeed forensic evidence of the crash still evident.

After careful and deliberate excavation, the site revealed more insight into who was flying the plane on that fateful day. Eventually, the link was established between the debris at the site and the Air Force pilot buried in Belgium.

First Lieutenant Shank was disinterred from the grave at the Ardennes American Cemetery and flown back home for burial in his hometown in Virginia. The First Lieutenant is among the American servicemen listed on the Wall of the Missing at the Cambridge American Cemetery and Memorial site in Cambridge, England. Although the names entered are permanent, when remains are recovered, a rosette is added to indicate the successful return of a soldier to his home.

The DPAA announced its gratitude to Mr. Oeltjebrun and the American Monuments Commission for their assistance with the disinterment and recovery, as well as the German government for its partnership. Thanks to the cooperation of these governments and people, and modern technology including mitochondrial analysis, anthropological analysis and other innovations, another brave soldier from the Second World War has been reunited with his loved ones.

There are more than 72,000 servicemen still missing from the American Armed Forces in locations worldwide. Of those, approximately 26,000 are considered “recoverable” by the DPAA.