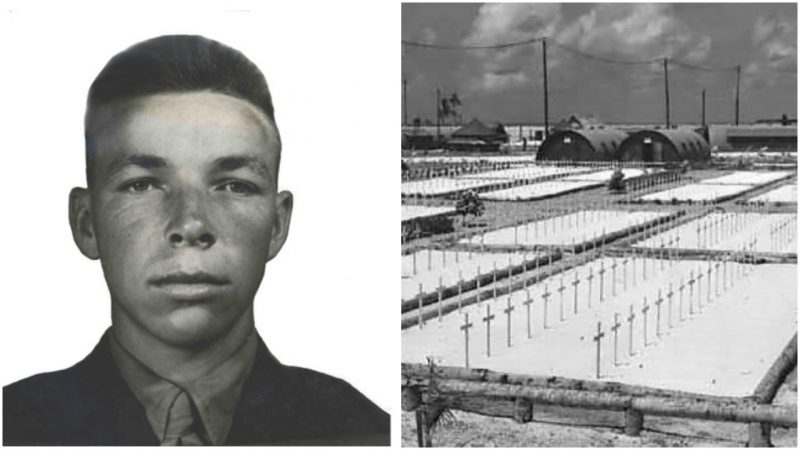

The remains of a Marine missing in action in the Pacific during the Battle of Tarawa, have been identified as Detroit teenager, Private First Class (Pfc) Arnold J. Harrison. Harrison was assigned to Company B, 1st Battalion, 2nd Marine Regiment, 2nd Marine Division, He was 19 when he died on November 20th, 1943, on the island of Betio, during the first day of the three-day conflict. Betio is part of the Tarawa atoll, south of the Marshall Islands.

The Battle of Tarawa marked the beginning of Operation Galvanic, the U.S. Pacific campaign against Japan, with the assault and capture of the Japanese-held island of Betio in the Tarawa Atoll in the Gilbert Islands.

The two-mile long and a half-mile wide island was defended by a garrison of at least 4,500 Japanese soldiers, who had heavily fortified the island with 100 dug-in concrete bunkers called pillboxes, seawalls, an extensive trench system for defensive movements and an airstrip. All of this was supported by coastal guns, anti-aircraft guns, heavy and light machine guns and light tanks. The island also sported natural terrain defenses that would impede movement, including shallow reefs covered with barbed wire and mines.

The attack would be the trial run of a new tactic, using combined arms coordination called ‘Atoll War,’ which consisted of subjecting the island and its defenders to bombardment by battleships and carrier planes prior to the invasion. Because of this, the United States sent in 18,000 U.S. Marines, expecting to easily take the tiny island. Except it wouldn’t prove to be that easy. Marines were to approach the shore in new amphibious tractor vehicles, dubbed amphtracs. These landing crafts, armed with machine guns and carrying 20 troops each, were able to crawl over shallow reefs and other barriers.

Unexpected delays would force the pre-invasion air raid to be delayed, which upset the timetable for other parts of the assault. This forced the bombardment support ships to linger in position longer than expected, and then having to dodge the accurate fire from the island, further upsetting the timetable. Compounding this, low tides presented obstacles to U.S. landing crafts attempting to clear the coral reefs surrounding the island, vastly reducing their mobility and leaving them at the mercy of Japanese coastal guns. Now desperate, the Marines left their boats and waded hundreds of yards through chest-deep water amidst enemy fire. The deep water claimed gear, including radios, and the constant exposure to machine gun fire meant many Marines were hit in the open water, which meant that the Marines who did make it ashore, did so ill-equipped, exhausted when they weren’t wounded, and unable to communicate.

Eventually, the superior numbers of the United States Marines deployed to take the island would win out, but within the 76-hour grueling engagement, almost as many Marines were killed-in-action as U.S. troops during the six-month campaign at Guadalcanal Island. Over the duration of the conflict on Tarawa, the casualty count included approximately 1,000 Marines and Sailors killed and more than 2,000 wounded, but the Japanese defenders were virtually annihilated.

American commanders learnt valuable lessons from the battle of Tarawa. They would apply these in future island assaults, including better reconnaissance, more precise bombardments, more and improved amphibious landing vehicles and, especially, better-waterproofed radios.

The fallen American troops were first interred in battlefield cemeteries, before being moved and buried on Honolulu in 1949. Pfc Harrison’s remains were disinterred from the Honolulu cemetery set up on the island, in January 2017, and identified using dental and other methods of analysis in October. His burial is scheduled for March 2, at Dallas-Fort Worth National Cemetery in Dallas.