Reputation can be just as daunting as reality, and never is that truer than during wartime. When the enemy is frightened of what he might encounter on the battlefield or at sea, what he does encounter is often not what he imagined.

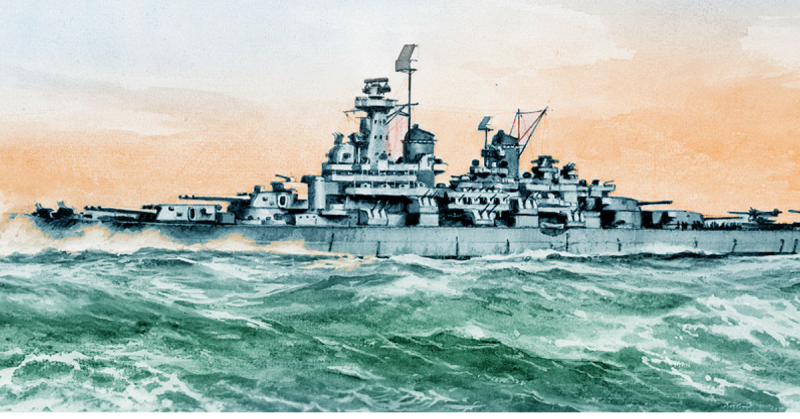

That was indeed the case with the Montana Class Battleships, intended for the U.S. Navy in World War Two. Not a single Montana ever hit the water, but the boats are still infused with almost mythical, legendary abilities that bear little resemblance to cold, hard facts. They were certainly not the boats that would, in one fell swoop, vanquish the enemy and win the war.

The Japanese warship Yamato was a crisis of sorts for the Navy, who at the time, because of Japan’s excellent security measures, didn’t realize just how massive and well armed the boat was. The Yamato was superior to the Navy’s Iowa class of ships, which were meant to be followed by the Montana. It was those capabilities more than the size that was the real cause for concern.

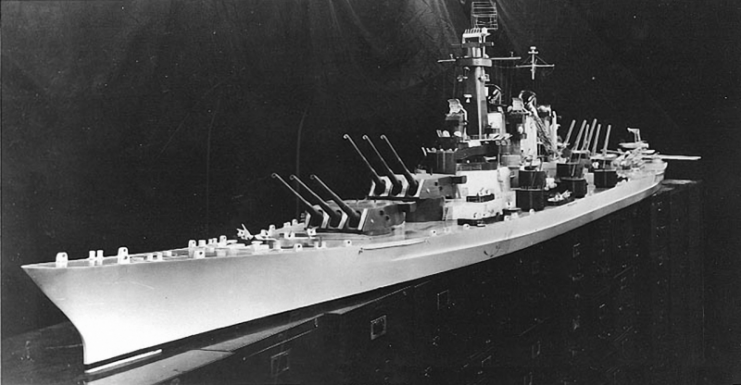

Comparing Montana to any other Navy ship the Iowa class, for example is fruitless, everything, not just size, was different. The Iowa class was not only smaller, it was faster, as those boats were intended to act as lead boats for carrier ships. The Montana, conversely, was designed to match all comers and, of course, to win. Her ammunition was unique, but perhaps more importantly, so was her armor. This area is where the Montana truly stood alone.

Bucking tradition, Navy designers used on the Montana an outer belt on which the armor was mounted to the outside of the hull. This device limited the degree of damage a hit could inflict, and ensured the ship’s watertight capability remained unscathed. These are just some of the differences between the Iowa and the Montana classes.

Imagine the Iowa running interference and deterring the enemy, and the Montana as a hulking hero who could be engaged on multiple fronts in this case, enemy ships. However, in the end, the Montana was not the warrior who could sail into battle and decidedly win the war. Nor did her designers ever intend her to be.

She was going to be just a battleship, a remarkable one, it’s true, but only a ship, with capabilities and restrictions that were the result of the limits and genius of the technology used by designers of that period.

A little known and often misunderstood fact about the Montana is that height was a crucial concern for the Navy. The reason was simple. At the time, one of the country’s biggest naval bases was in New York, which could only be accessed by passing under the Brooklyn Bridge. A tall man can duck if a doorway is too short, however, a ship cannot “duck” under a bridge. If a boat wanted access into the harbor and the base, it had to be short enough.

However, some boats attract mysteries and legends, and the Montana class is undoubtedly one of them. Ultimately, however, it is impossible to know just how large or small a contribution to the war effort a Montana class battleship would have made, aircraft carriers proved to be more valuable when Montana was still in the early stages.

History has taught us no single vehicle, on land or at sea, is responsible for winning the war. That was achieved by a concerted, sustained effort by Allies of markedly different nations pulling together, on land, in the air and yes, on the sea.