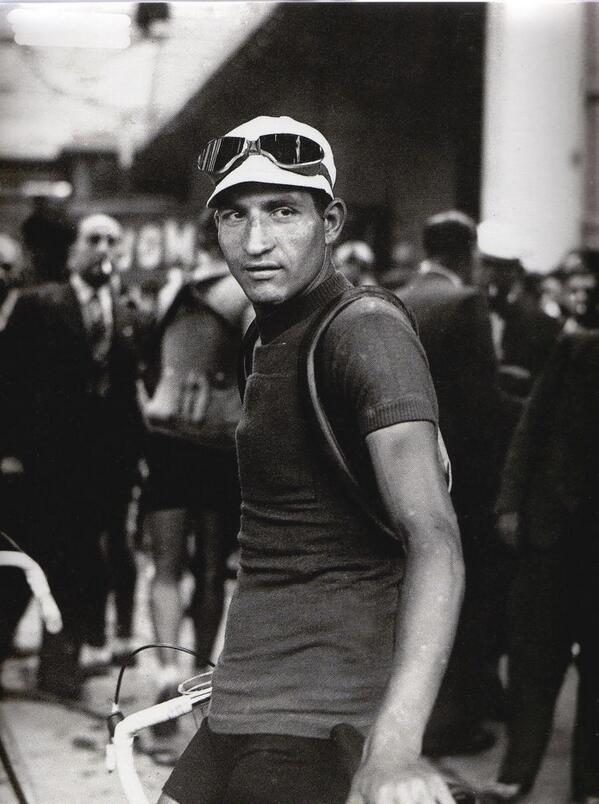

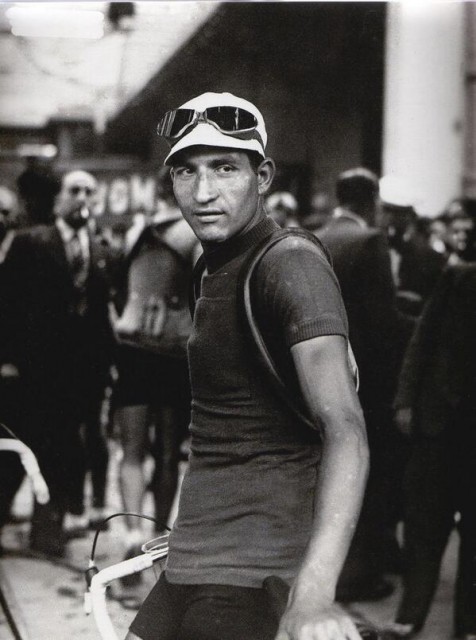

Gino Bartali was a famous Italian cyclist who won several titles in the 1930’s, including three Giro d’Italia events, a key cycling competition in Europe, and the Tour de France in 1938. His country was proud of him, and he was very much a recognizable public figure.

But Bartali had a secret life, one that saved the lives of hundreds of Italian Jews when the Nazis invaded Italy in 1943.

My Italian Secret is a new film directed by Oren Jacoby that tells the story of Bartali’s secret involvement with a resistance movement that was put in place to hide Jews and prevent them from being captured and send to the Nazi concentration camps during World War II.

Bartali would hide counterfeit identity papers inside his bicycle’s handlebars, and deliver them to Jews who were hiding from the Nazis in order for them to escape. He risked his own and his family’s lives to save many others.

Bartali was born in 1914 in Florence to Catholic parents who had been married by Cardinal Elia Angelo Dalla Costa. Della Costa had created a secret program to save the lives of Jews in Italy once the Nazi’s had taken over much of the country. He recruited Bartali to work with him.

Quite a number of Jews had left Italy after Benito Mussolini forbade them intermarrying and from working in the media, the government or in education. But many remained. From 1938 until 1943, these Jews remained unharmed. Then the Germans invaded.

Della Costa and Rabbi Nathan Cassuto worked together to organize a system that would provide Jews with places to hide, such as monasteries and convents, or in people’s homes. Although Cassuto ended up being captured, deported, and executed, the system continued to be successful.

Bartali would ride his bike for hundreds of miles delivering identity papers under the ruse that he was training for long distance cycling, and easily get past the Fascist police officers because of his popularity and because they admired him. If he was stopped, he would ask them not to touch his bike because it was set up a certain way to allow him to ride with optimum speed.

Giorgio Goldenberg, an Italian Jew who Bartali had hidden in his cellar during the war, explains in his book, Road to Valour, how Bartali saved his and his family’s lives as well as hundreds of others. He refers to Bartali as a hero.

Trento Brizi was one of the men responsible for creating the counterfeit papers that Bartali delivered. He noted that when the Nazi’s started to get suspicious, it was Bartali and his fearlessness that gave him the courage to continue. He further explained that he was so proud to work with Bartali that he was able to put his fear on hold.

The number of Italian Jews that were killed by the Nazis was 7680 out of a possible 44,500, according to the Jerusalem Holocaust museum, Yad Vashem.

Although numerous Italians defied Hitler’s plan to kill all the Jews in Europe, Bartali was more at risk than most due to being so well known. Yet Bartali would not take any credit for saving Italian Jews, and was very modest about his contributions to the cause, the CNN Edition reports.

Although Bartali passed away 13 years earlier in 2000, he was recognized as a Righteous Among the Nations in September 2013, which is Israel’s official memorial to victims of the Holocaust. At the ceremony, Bartali’s son, Andrea, met a number of survivors who were saved by his father, including Goldenberg. Andrea has been instrumental in making his father’s secret known to the public.

Speaking of his father, Andrea explained that he didn’t consider himself a hero, just a cyclist, and that the real heros are those who have endured suffering.

When the film about Bartali was released in Rome, it gave Italians a chance to learn of a piece of their country’s history that had previously been cloaked in secrecy. The film’s director, Jacoby, had always been intrigued with how the Italians were able to defy the Nazi’s.

In 1975, he had met a Polish filmmaker,Marian Marzynski, who had told him about surviving as a child by hiding in people’s homes and in a monastery. Everyone who helped to save him had put their lives on the line. Now, nearly 40 years later, Jacoby felt honored to be working on a story about heroes who risked their lives for others.

While directing the film, Jacoby met up with the son of another hero, Dr. Giovanni Borromeo, who worked as a surgeon at the Catholic Fatebenefratelli Hospital in Rome during the war.

At the time, Borromeo told the Nazi’s that the hospital had become infected with a terrible disease he named Il Morbo di K in order to prevent them from entering and searching for Jews. He hid hundreds of Jews in the hospital under the cover of this fake illness. During the screening of the film, some of the Jews that had been hidden in the hospital showed up.

Before he died, Bartali met up with Rabbi Cassuto’s daughter, and agreed to tell her about the work he did with her father as long as she did not record the conversation.

Every year, Bartali’s achievements in cycling are remembered in a dedication at the Settiman Coppi e Bartali race. But his secret life as a war hero will never be forgotten.