Jewish people are said to have first settled in Bulgaria in the year 46 CE. They’ve created a long and rich history over their almost-2,000 years in the country, yet very few still live there. The vast majority left during and immediately after the Second World War, after being persecuted for their faith.

Bulgaria didn’t want to be involved in World War II

Bulgaria was one of the losers of World War I, and lost territory during both that conflict and the Second Balkan War. As a result, the country planned on staying neutral during World War II. That neutrality, however, had ulterior motives attached to it, as Bulgaria hoped to regain the territory it had lost, without having to fight.

Despite taking a neutral stance, Bulgaria still had important ties to Germany, as the pair’s relationship accounted for 65 percent of Bulgaria’s trade economy.

In August 1939, Russia and Germany signed the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact – a non-aggression pact that allowed the two nations to split Poland between themselves. Following the agreement, many European countries attempted to curry favor with the German regime. Bulgaria did this, in part, by passing legislation that was antisemitic in nature.

Bulgaria attacked its Jewish citizens in an attempt to appease Germany

With Germany gaining power, Bulgaria hoped to stay in its good graces, and did so by attacking Jewish citizens. In January 1941, the country passed the Law for Protection of the Nation. Under the legislation, Jews would be refused Bulgarian citizenship and were required to fulfil their compulsory military service in labor battalions, not the regular army.

The passing of the act was in addition to other prohibitions against Jews, including changes to their names, exclusion from public service and politics, restrictions on places of residence, prohibitions on economic and professional activity, and the confiscation of property.

It also presented measures that would make it more difficult for foreign Jews to enter the country. While there was significant opposition to allowing in refugees, Bulgaria eventually did agree to issue a small number of visas.

Bulgaria begins plans to deport Jews

In January 1942, German leaders held the Wannsee Conference. At the meeting, the Germans discussed how they would implement their “Final Solution,” which called for all Jews in German-controlled European countries to be deported to Poland and summarily executed.

The Bulgarians found it important to please the Germans, despite their position of neutrality. When asked to release the country’s Jews into German custody, Bulgaria agreed and began taking steps toward their deportation.

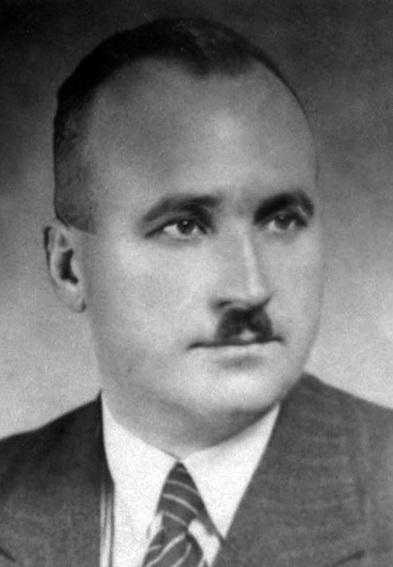

In June 1942, Interior Minister Petar Gabrovski established the Commissariat for the Jewish Affairs in Bulgaria. Arrangements were made with the Reich Security Main Office to deport 8,000 Jews from the town of Sofia. In addition, 13,000 more were to be deported from the Bulgarian-occupied areas of Thrace, Macedonia and Pirot.

Deportations begin

The Bulgarian government began deporting Jews in March 1943. 4,500 Jews in occupied Macedonia and Thrace were sent to Poland, while 7,144 from Vardar and Pomoravlje were sent to Treblinka. None of them survived. There were plans to deport an additional 48,000 Jews, but these never materialized. By the end of WWII, no Jews in Bulgaria proper were deported to concentration camps.

There was also significant resistance in the country. Dimitar Peshev, who had served as Bulgaria’s Minister of Justice prior to WWII, was opposed to the Germans and helped organize protests against the deportations, alongside the Bulgarian Church and other citizens. He was also able to convince Gabrovski to halt the deportations. While Gabrovski agreed, the message did not get through before the initial 13,000 Jews were sent away. The 48,000 remaining in Bulgaria, however, were saved.

In 1973, Yad Vashem honored Peshev with the title of Righteous Among the Nations.

The remaining Jews in Bulgaria are rescued

Peshev and others in the government continued to work to protect the Jews, and protests continued throughout the country. Eventually, Tsar Boris III was convinced to cancel the deportations. Bulgarian officials reported to German leadership that the country’s remaining Jewish population was needed for railroad construction and other projects.

Life was not easy for those who remained, but they avoided deportation to Poland.

The vast majority of Bulgarian Jews left the country for Isreal, with 43,961 people emigrating there between 1948 and 2006. As of the last census, which was conducted in 2010, around 2,000 Jews remain in Bulgaria.