In 2019, U.S. correctional facilities—spanning federal, state, and military prisons—held a combined total of 1,380,427 people. Over the past hundred years, the treatment of incarcerated individuals has undergone major changes. Modern federal prisons are structured to promote personal development, teach useful skills, and help inmates prepare for a successful return to society.

While federal and military prisons share certain similarities, they each have unique roles and operate under different regulations. As a result, the day-to-day experience of inmates can vary significantly depending on where they’re confined. Federal prisons house individuals convicted of a broad spectrum of crimes and often place a strong emphasis on rehabilitation. In contrast, military prisons specifically detain service members who violate military law, focusing on enforcing discipline and upholding the standards of the armed forces.

What is a military prison?

Military prisons are usually used to hold prisoners of war (POWs), unlawful combatants, individuals who threaten national security, and military personnel convicted of serious crimes. These facilities are different from regular prisons and generally fall into two categories: penal, which focus on punishment or rehabilitation, and security-focused, which hold people considered a threat.

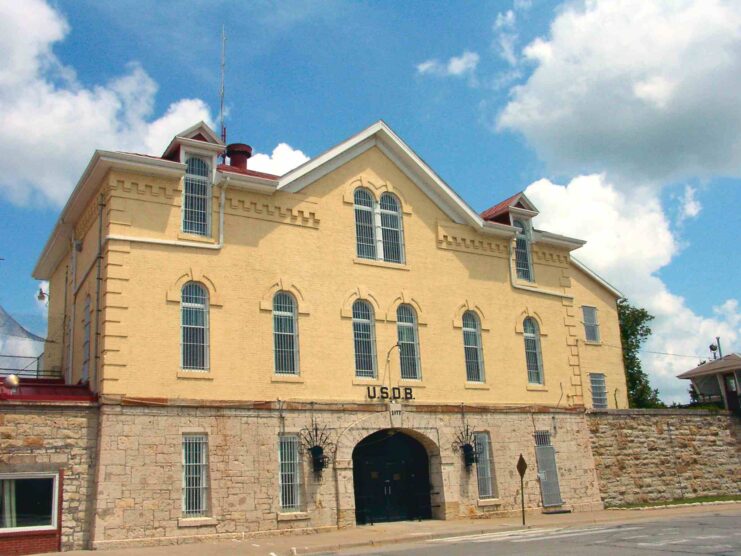

The U.S. military’s prison system is organized into three tiers, with a total of 59 facilities. Level One is the lowest and mainly includes inmates before or after their trials who have sentences of one year or less. Level Two holds the majority of prisoners, with sentences of up to seven years. Level Three uses the high-security prison at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas to house the most dangerous offenders.

Military prisons have changed a lot since they first opened

Since the establishment of the first military prison in 1874, the way these institutions operate—and the profiles of the inmates they hold—has changed dramatically. In the early days, desertion and similar offenses were frequent reasons for imprisonment. But with the end of the draft in the 1970s, the nature of military crime shifted toward more severe violations. By 2002, offenses like assault, drug possession, and drug trafficking topped the list of reasons service members ended up behind bars. Most inmates at the time were White men with high school educations, often convicted of crimes involving harm to others.

Military prisons have maintained their effectiveness thanks to a rigidly organized environment. These facilities typically offer vocational training, counseling, and various support services. Some even implement military-style boot camps designed to reinforce discipline. Over the years, these approaches have inspired similar programs in the civilian correctional system, shaping how federal prisons support rehabilitation.

But what is daily life really like for inmates in a military prison—and how does it stack up against doing time in a civilian facility? Let’s take a closer look.

The facilities differ between military and civilian prisons

Military prisons operate under the same strict standards and protocols as the rest of the Armed Forces, emphasizing discipline and structure. Just like in basic training, inmates are required to maintain a clean and organized environment. Failure to do so results in immediate disciplinary action. With robust funding from the military, these facilities tend to be in excellent condition and well-maintained.

On the other hand, civilian prisons, including federal ones, often face resource limitations and receive less financial support. While inmates are still expected to keep their spaces clean, the lack of structured oversight and fewer resources make it harder to enforce these standards consistently. As a result, maintaining cleanliness can become less of a priority in many civilian correctional facilities.

Military prisons follow a strict daily schedule

Military prisons begin their day at 6:00 AM with roll call. In typical military fashion, inmates follow a strict schedule that consists of meals, maintenance and workshops. Weekends feature more time for relaxation and recreation.

Military prisons have better food

Food is a big part of prison life, and military prisons are known for having much better meals than civilian facilities. Guards in military prisons have strict rules in place that prohibit inmates from taking food outside of the dining hall, while civilian inmates have little to no oversight regarding this, allowing for trading to occur. Federal institutions also have access to a commissary that allows prisoners to purchase food and other goods.

Civilian prison guards are more likely to be corrupt

Military prisons are generally staffed by military police or personnel from local security forces units. These guards, as members of the armed forces themselves, are held to the same standards of conduct and discipline as the inmates they oversee. Because they’re trained to serve across all military branches, they tend to approach their duties with professionalism and often show respect toward those in custody.

In contrast, civilian prisons can present a more unpredictable dynamic. Some guards take a laid-back approach—doing their rounds and then keeping to themselves—while others lean heavily on their authority, using fear or intimidation to maintain control. This often creates friction and fosters distrust among inmates. In more troubling cases, some civilian guards exploit their power, leading to mistreatment. Such abuse is less common in military facilities, where a shared code of conduct and mutual accountability help keep such behavior in check.

Military prisoners aren’t allowed to salute their fellow officers

While most aspects of life in a military prison are surprisingly similar to life in the service, one important tradition is actually prohibited: the salute. Military inmates aren’t allowed to salute officers; doing so is actually a punishable offense. Prisoners aren’t allowed to salute officers because it’s seen as inappropriate for a superior to return the gesture.

Ranks are removed for inmates

Ranks are also removed upon imprisonment. In 2012, Lt. Col. Ken Pinkela was found guilty of felony assault, willful disobedience, abusive contact and conduct unbecoming of an officer. He was taken to the US Disciplinary Barracks at Fort Leavenworth to serve out his sentence.

As one of the highest-ranking inmates, Pinkela struggled to come to terms with his loss of rank, which he’d worked for 20 years to achieve. “In Leavenworth, your former rank carries no weight,” he told The Marshall Project. “On the day I went in, the silver oak leaves emblazoned on my uniform that signaled what I was were taken away from me, and I became an inmate – a prisoner to a country that I swore to protect and serve.”

Use of solitary confinement

One of the more harrowing parts of imprisonment is solitary confinement – or “the hole.” The punishment is used in both military and civilian prisons if an inmate disobeys an order or commits an offense. According to Quartz, solitary confinement in the US is “inflicted upon at least 80,000 inmates, including juveniles, often for months or years.”

No human interaction

Military prisoners can be placed in solitary for up to six months, where they sit in an eight-by-seven-foot room with a toilet, sink, bed and light. They receive no human interaction, with food shoved through a small slot in the door. Sometimes, all it takes to be thrown into solitary is having old toothpaste.

Former US Army soldier Chelsea Manning, who was imprisoned at Fort Leavenworth, was threatened with indefinite solitary confinement for possessing expired toothpaste, dropping food on the floor, and allegedly having copies of Vanity Fair and Cosmopolitan.

Rehabilitation of prisoners

One of the main objectives of prison is to rehabilitate criminals and prepare them for reentry into society. Rehabilitation programs are especially important for military prisoners who will be given a dishonorable discharge upon their release, as they’ll need a new skill or trade upon reentering the civilian world. Military prisons offer training for inmates in carpentry, auto repair, cooking, hospitality and more.

More from us: Here’s Why Saddam Hussein’s Plan to Engage the Coalition in WWI-Style Trench Warfare Failed

Civilian prisons also provide inmates with opportunities for learning and growth. Resources to obtain high school diplomas, learn skilled trades and special programs for substance abuse are provided. Inmates can also take college courses, at their own expense. Unfortunately, these opportunities are not as readily available to civilian prisoners as they are to military inmates.