Capt. John R. “Bob” Pardo was assigned to the 8th Tactical Fighter Wing, 433rd Tactical Fighter Squadron, which attacked an integral North Vietnamese steel mill. During the engagement, the aircraft flown by Pardo’s wingman suffered serious damage, enough to cause the pilot to eject into enemy territory. Not wanting to leave his comrade behind, the former launched a risky attempt at “pushing” the aircraft toward safety. This became known as “Pardo’s Push.”

Attack on the Thai Nguyen Steel Mill

In early 1967, the US Air Force prepared for an air strike on the well-defended Thai Nguyen Steel Mill north of Hanoi. The mill, used to produce war material for the North Vietnamese, had long been listed as the top industrial target in the area. However, up until this point, it had been off-limits, due to constraints enforced by Washington.

After those were lifted, the attack was planned for the beginning of March. It would have to wait, however, as intense weather conditions and heavy cloud cover caused a nine-day delay.

On that day, Capt. Bob Pardo, weapons systems officer 1st Lt. Steve Wayne, wingman Capt. Earl Aman and weapons systems officer 1st Lt. Robert “Bob” Houghton were to fly their McDonnell Douglas F-4C Phantom IIs to the target and assist by defending other aircraft against enemy MiG retaliation. In the case there weren’t any, they were to join in attacking the steel mill directly.

As it turned out, there were no MiGs present, so Aman and Houghton dropped their bombs on the mill. There was heavy anti-aircraft fire from the enemy, and several US aircraft were shot down. Aman and Houghton’s F-4 was hit by flak, but they were still able to proceed with the task at hand. The hits proved to be extremely damaging, however, causing gas to leak from their fuselage. They subsequently concluded they wouldn’t have enough fuel to fly themselves to safety.

Pardo and Wayne’s F-4 wasn’t in much better shape, having also taken a hit from anti-aircraft fire. Their fuselage had suffered damage, causing them to lose fuel as well, but at a much lesser rate. Still, they weren’t entirely sure their aircraft could make it to the pre-briefed rendezvous point, where a fuel tanker was waiting.

After it became clear that Aman’s aircraft wasn’t going to make it to the tanker, Pardo radioed him, saying, “I’m gonna try to give you a push. Fly that thing as smooth as you’ve ever flown.” He later explained, “I couldn’t see leaving a guy I’d just fought a battle with.”

Bob Pardo had to try different methods while running out of time

Despite the damage the aircraft had taken, their handling remained relatively normal. As such, both F-4s climbed to 30,000 feet, to try and extend their glide as much as possible before running out of fuel. Pardo’s hope was that he could at least get the two out of enemy territory. “We’ll do our d******t to help you out of here!” Pardo radioed to his wingman.

Initially, the pilot planned to tuck the nose of his F-4 against the tail of Aman’s, to push both forward enough to eject into the Laotian jungle. He told the wingman to “jettison your drag ‘chute,” so he could snuggle into a stable push point near the fuselage. Unfortunately, this wasn’t going to work. “There was so much turbulence coming off his airplane that I couldn’t even get within 10 feet of him,” Pardo later recalled. He had to think up a new plan.

Switching tactics, Pardo flew his aircraft under Aman’s to slowly rise up and “lift” his wingman’s F-4 from its belly. The plan was to essentially carry the more damaged aircraft piggyback style to the border. However, he quickly realized:

“When I got about a foot from him, the nose of my airplane started trying to come up, up, up. I thought, This is not good because we could smash our canopies, which would be a problem if we had to eject, which it looked like we were going to have to do because we were obviously getting low on fuel too.”

Having tried two different approaches, time was running out. At this point, Aman had to shut down his engines, radioing Pardo, “We’re out of fuel! Both our engines have just flamed out!” Additionally, his aircraft was descending at an alarming 3,000 feet per minute. Pardo pulled back from under Aman’s F-4, and it was at that moment he figured out another possible approach for pushing his wingman to safety.

Pardo’s Push

When Pardo came out from under the belly of Aman’s F-4, he spotted the steel tail hook at the rear end of the fuselage. This is designed to stop aircraft as they land on aircraft carriers, meaning they’re built to be extremely strong. Knowing this, Pardo radioed Aman to “put the hook down.” Once it was, he flew his F-4 against it. Immediately, the aircraft’s descent was halved to 1,500 feet per minute – a solution had finally been found.

At first, Pardo pressed the tail hook against his windshield, but this was proving dangerous, as the pressure caused cracks in the windscreen. If that were to break, the powerless F-4 would crash into Pardo’s cockpit, so, he repositioned the tail hook to rest against the metal base of the glass.

The rest of the push didn’t come easy. The tail hook was designed to swivel, and Aman’s dislodged itself from Pardo’s aircraft almost every 30 seconds. Additionally, Pardo’s left engine caught fire during the push, forcing him to shut it down, increasing their descent to 2,000 feet per minute.

With only one engine pushing the two F-4s, it didn’t look like they were going to make it out of North Vietnam. In an act of sheer necessity, Pardo restarted the closed engine. He had Wayne inform him when the gauge began to flash, at which time he would momentarily shut the engine down. He continued to do this for about 10 minutes, dangerously, yet successfully pushing both across the border.

They weren’t guaranteed safety in Laos

Now that the two F-4s had made it out of North Vietnam, Pardo radioed the US search and rescue crew their position. At around 6,000 feet, Aman and Houghton ejected, injuring their backs in the process. On the ground, there was an armed Laotian guerrilla group heading their way, whose position Houghton also radioed. A minute later, Wayne also ejected, and the three connected on the ground, evading the guerrilla group until they were rescued.

The right engine of Pardo’s F-4 had, by this point, been entirely exhausted of fuel, ultimately flaming out and causing him to eject shortly after Wayne. However, when he ejected, he lost consciousness and fractured two vertebrae in his neck. The pilot also injured his back. After regaining consciousness and at risk of being spotted by the guerrilla group, Pardo painfully made his way half a mile up a hill to await rescue. It took the rescue crew about 45 minutes to locate him.

Pardo’s Push, as it became known, lasted for approximately 20 minutes, with Pardo successfully guiding both aircraft nearly 90 miles. “When we got to the club, man, we couldn’t buy a drink,” he recalled. “We had a pretty good party until about midnight.” The party didn’t last long, though, as Pardo was later reprimanded for the damages caused to his F-4.

More from us: Paris Davis’ Heroics in Vietnam Warrant the Medal of Honor – Why Hasn’t the US Army Awarded Him It?

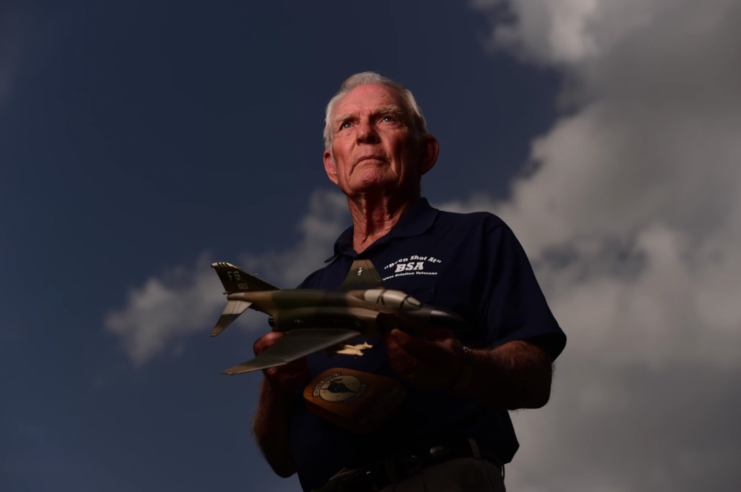

It would be two decades before Pardo and his colleagues were recognized for their bravery. In 1989, he and Wayne were awarded the Silver Star, given in recognition of their gallantry in connection with military operations against an opposing armed force over North Vietnam.