MACV-SOG’s top-secret beginnings

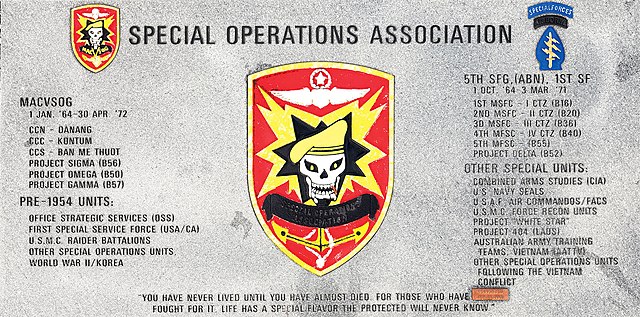

On January 24, 1964, the Military Assistance Command, Vietnam – Studies and Observations Group (MACV-SOG) was officially formed. This elite unit brought together top operatives from across the U.S. military, including Green Berets, Navy SEALs, U.S. Air Force Commandos, CIA agents, and Marine Corps reconnaissance veterans, creating one of the most highly skilled teams of the Vietnam War.

At first, MACV-SOG’s operations were overseen by the Special Assistant for Counterinsurgency and Special Activities within the US Department of Defense, allowing the unit to conduct missions beyond South Vietnam’s borders. As the group’s role expanded, oversight eventually shifted to the military.

Many of MACV-SOG’s covert missions took place in North Vietnam, where secrecy was essential to maintaining the official narrative that U.S. forces were only operating in South Vietnam. The group also carried out operations in Laos and Cambodia, focusing on the Ho Chi Minh Trail, a vital supply route for the North Vietnamese Army (NVA).

Because of the extreme risks involved, MACV-SOG was made up entirely of volunteers. The danger was so severe that the unit faced a staggering 100 percent casualty rate, with members knowing that their service would likely earn them either a Purple Heart or a flag-draped casket.

Unidentifiable Americans

Because of the highly sensitive nature of their operations, MACV-SOG had to comply with strict uniform guidelines to blend in seamlessly with South Vietnamese forces. They adopted the unique tiger stripe camouflage worn by their allies and eliminated any visible identifiers, such as dog tags or patches. Likewise, the Green Berets refrained from wearing their signature headgear.

For armament, MACV-SOG operatives commonly carried either a CAR-15 or an AK-47, along with M79 grenade launchers. TTo prevent identification, all serial numbers on these weapons were carefully removed. Each weapon was carefully secured to reduce noise during movement; rifles were carried with canvas straps, while M79s were secured using tape-wrapped D-rings.

In addition to firearms, operatives carried other weapons, including fragmentation grenades and V40 mini grenades, reflecting the unconventional nature of their operations. For example, Staff Sgt. Robert Graham, a MACV-SOG member, famously relied on a 55-pound bow with razor-sharp arrows when normal ammunition ran out.

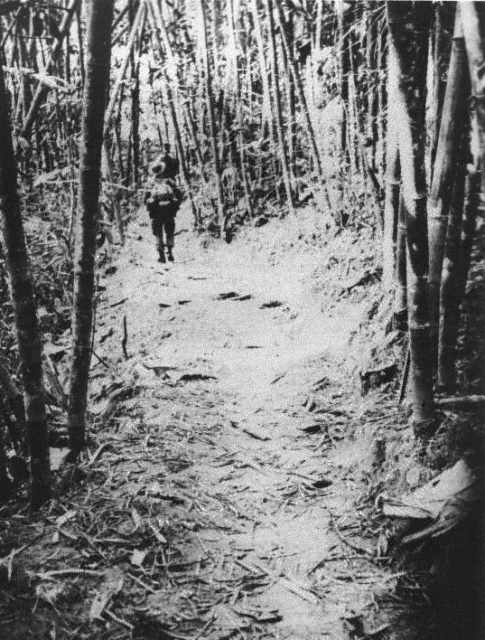

Ho Chi Minh Trail

MACV-SOG’s primary theater of action was the Ho Chi Minh Trail, a vital supply route for North Vietnamese forces and a central focus in the effort to disrupt guerrilla activity. The group’s role was crucial, serving as field operatives responsible for intelligence gathering in support of Saigon. Their missions involved reconnaissance, document retrieval, and intercepting enemy communications—tasks that demanded extreme precision and daring.

These operations were fraught with danger and required close collaboration with local forces, who made up the majority of each team. Typically, two to four American personnel worked alongside a contingent of four to nine South Vietnamese guerrillas.

In an interview with History of MACV-SOG, Jim Bolen elaborated on the challenges of operating along the Ho Chi Minh Trail, noting that the trails were often close to large enemy encampments with thousands of soldiers, making the missions particularly high-stakes. Famous missions like the Thanksgiving Day 1968 operation, where a six-man team faced an overwhelming enemy force of 30,000 troops, underscored the extreme risks involved. Similarly, Frank D. Miller’s lone encounter with 100 NVA troops exemplified the perilous nature of these covert operations.

MACV-SOG operations behind enemy lines

Through efforts like this, MACV-SOG providing 75 percent of the intelligence gathered by the U.S. military on activity along the trail.

Beyond reconnaissance, the unit had a critical secondary mission: capturing enemy personnel deep behind hostile lines. These operations ranked among the most dangerous tasks, sometimes serving as the primary objective, other times supporting broader missions—but consistently received strong backing from military command.

Prisoner snatching behind enemy lines

MACV-SOG operatives were motivated with $100 for each enemy soldier they captured, along with promised rest and relaxation (R&R). Local informants and collaborators also received rewards, ranging from cash to new watches. These incentives proved highly effective, allowing the teams to achieve significant captures—such as seizing 12 enemy soldiers in Laos in 1966—which provided crucial intelligence on troop movements, base locations, and enemy strength.

Prisoner captures required careful planning and ingenuity. Operative Lynne Black, for example, calculated precise amounts of C-4 to incapacitate targets without causing fatalities, using trial and error to refine the method. Explosives were placed along enemy trails and detonated at just the right moment, rendering soldiers unconscious for swift and safe capture.

Throughout the Vietnam War, MACV-SOG played a key role in major operations, including Steel Tiger, the Tet Offensive, Tiger Hound, Commando Hunt, and the Easter Offensive. Despite their significant impact, the unit’s daring missions remained classified until the 1980s, keeping their extraordinary expertise and courage hidden from public view for decades.

More from us: Despite Being Up Against 2,000 Enemy Troops, Bernard Fisher Risked His Life to Save a Fellow Airman

The group’s members weren’t formally recognized until 2001 when they received the Presidential Unit Citation.