Siegecraft, or the art and science of surrounding and isolating enemy forces within a town or fortress, was an important element of eighteenth-century conflict and the American War of Independence. Most Revolutionary War enthusiasts and novice historians are, at a minimum, at least familiar with several popular sieges that dictated the overall outcome of the conflict.

The year-long Siege of Boston (April 1775 – March 1776), for example, was one of the most crucial conflicts during the opening years of the war and famously concluded with the establishment of the Continental Army.

A few years later, the Great Siege of Gibraltar (1779 – 1783) ended up being one of the largest continuous actions of the Revolutionary War, despite the battle being waged over 4,000 miles away from North America.

In all, over a dozen sieges took place during the Revolutionary War, with a majority of the action occurring in North America. Belligerents on both sides of the conflict either conducted or attempted to resist these siege actions.

A vast majority of the operations were led by British or American commanders who possessed varying amounts of relative experience in siegecraft.

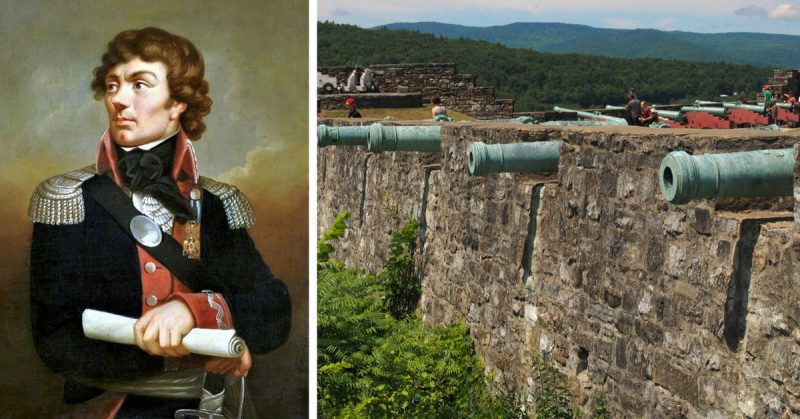

One figure, however, stands out from the rest for a unique reason. That man was Tadeusz Kościuszko, a Polish combat engineer who fought alongside American Patriots during the Revolutionary War and was commissioned as a colonel in the Continental Army.

Kościuszko (commonly pronounced in English as Ko-shoo-sko) is one of the most famous military figures in Polish history and was hailed as hero in both America and his native Poland during his lifetime. In 1746, Kościuszco was born into a prominent household in the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth (a contested duchy partitioned between Russia, Austria, and Prussia, now part of present-day Poland).

He was the product of a military education, excelling in his studies—first, at the Szkoła Rycerska (Warsaw Corps of Cadets) and later in France.

As a foreigner, Kościuszko was barred from enrolling in French military academies. Instead, he pursued studies at Paris’s Académie Royale de Peinture et de Sculpture (Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture). He developed his skills as an artist under the famous French architect, Jean-Rodolphe Perronet, while independently forging his own path as a siege engineer.

Ultimately, it was the combined influences of his studies in Warsaw, Perronet’s tutelage, and the French Enlightenment that contributed to Kościuszko’s education and development in the art of siege warfare.

Kościuszko returned to his native Poland in 1774, where he discovered that his brother, Józef, had wasted and misspent his family’s wealth. Consequently, Kościuszco was unable to purchase a commission (a common practice of the period) and was forced to look for employment opportunities abroad.

After being turned down by military officials in both the Free State of Saxony and France, Kościuszko looked across the globe where the Revolutionary War was gaining momentum in North America. He set sail for the colonies the following summer and was accepted into the Continental Army on August 31, 1776.

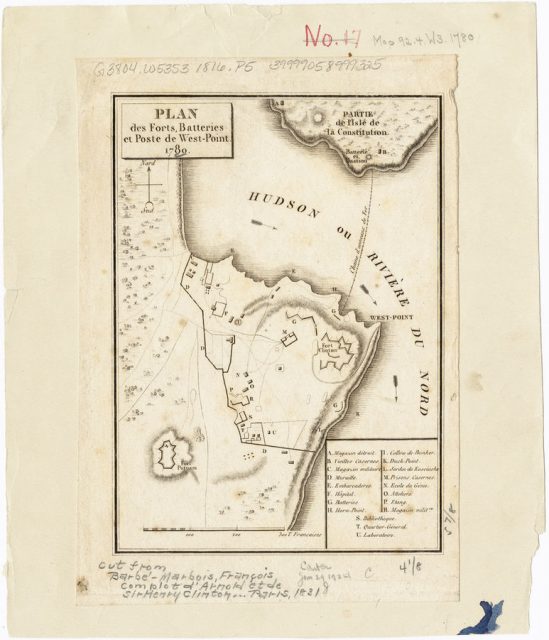

The young Polish officer initially served as a volunteer but was later commissioned as a colonel in the Continental Army. One of his initial assignments was the fortification of Fort Billingsport on the banks of the Delaware River.

A few months later, Kościuszco was assigned to General Horatio Gates’s Northern Army where he quickly set about the task of shoring up the defenses at Fort Ticonderoga, a massive fortress that Patriot forces captured from the British just two years earlier. Kościuszko quickly identified a strategic weakness in the fort’s defenses, namely that it sat in the shadow of Mount Defiance.

The ridge later became the location where British General John Burgoyne famously stationed cannons that he used to reclaim the fortress for the Crown during the infamous 1777 Siege of Fort Ticonderoga. There’s a strong argument that things might have turned out differently had the fort’s Patriot commander, Brigadier General Arthur St. Clair, acted on Kościuszko’s recommendation prior to the siege.

Kościuszko remained undaunted, despite having to abandon the fort to the British, and was instrumental in delaying the pursuing redcoats as they chased the Patriots south to Saratoga.

Ever the capable engineer, Kościuszko directed his men to destroy bridges, dam streams, and place fallen trees in the path of the advancing British, who faced a soggy grind through the unforgiving wilderness.

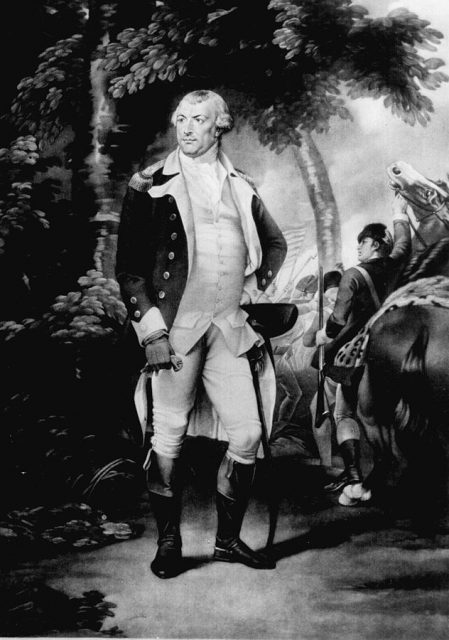

Later, at the Second Battle of Saratoga, Kościuszko was credited with masterminding the defenses at Bemis Heights, an engagement where an overwhelmed and fatigued Burgoyne eventually surrendered to Patriot forces on October 17, 1777.

In the Southern Theater of the war, Kościuszko continued to contribute to the revolutionary cause across several fronts.

In addition to lending his engineering skills to Major General Nathanael Greene, Kościuszko earned a reputation as a reliable intelligence officer. He scouted out locations for several important camps and established many reconnaissance contacts, which shielded Greene’s Southern Army from an enraged General Cornwallis who relentlessly pursued the Patriots across the Carolinas.

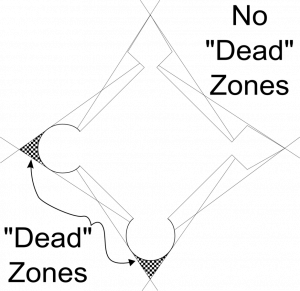

Kościuszko’s last major engagement of the war took place in present-day Greenwood County, South Carolina where he orchestrated the cordoning of the Loyalist Star Fort during the Siege of Ninety-Six (May 22 – June 18, 1781).

The Patriots greatly outnumbered the Loyalist militia, with Greene mustering about 1,500 men to the Loyalist John Cruger’s 500. Despite their numerical superiority, however, the Loyalists put up stiff resistance.

Patriot commanders, under Kościuszko’s guidance, spent the better part of a month digging parallel trenches and edging their sappers closer and closer to the Star Fort. Under a near-constant barrage of Loyalist fire, the Patriots eventually managed to dig a 30-foot-long trench, from which they launched an unsuccessful assault.

Kościuszko additionally supervised the construction of a Mahan Tower—a mobile platform manned by Patriot sharpshooters who shot muskets, rifles, and flaming arrows down into the fort. Cruger countered this tactic by shoring up the Star Fort’s walls with stacks of sandbags and was ultimately rescued by the British General Francis Edward Rowden who brought some 2,000 British regulars to Cruger’s aid.

Kościuszko received a bayonet wound during the failed siege but went on to participate in a few minor skirmishes near the end of the war.

Kościuszko later returned to his native Poland where he fought a losing battle against the Russian Army during the early 1790s. The Polish government eventually surrendered to Catherine the Great who forced Kościuszko into exile.

He returned to Poland two years later, made significant changes in the army, and successfully resisted Russian and Prussian forces during the Siege of Warsaw (1794). A wounded Kościuszko was eventually captured by the Russians, however, dealing a devastating blow to the Polish resistance.

Poland was subsequently divided between Russia, Prussia, and Austria, effectively destroying the country’s nationhood until it was reinstated during the early twentieth-century.

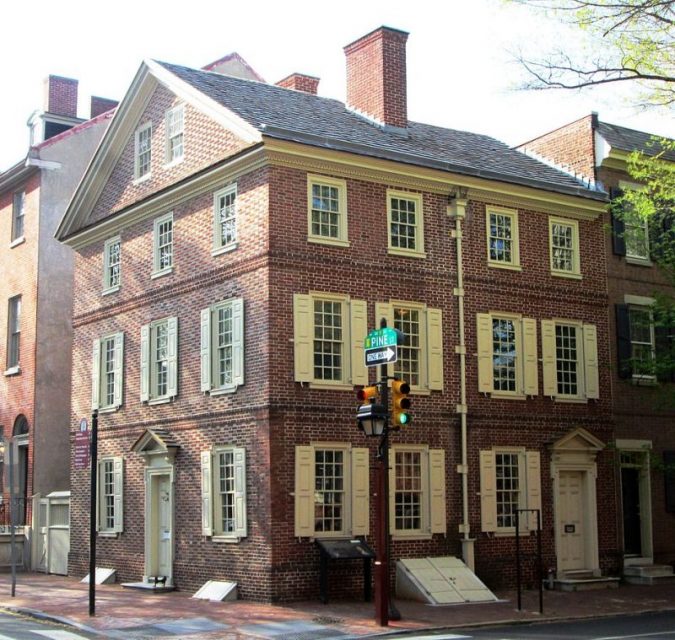

The dejected Polish officer remained in exile for the remainder of his life. Kościuszko traveled back to America, in 1797, where he was welcomed as a hero and befriended by Thomas Jefferson. The two men remained good friends until Kościuszko eventually passed away in Switzerland on October 15, 1817.

Although he died in exile, Kościuszko’s remains were later relocated to several locations in Poland and eventually interred at the Royal Castle in Kraków, in 1927. Today, he is remembered as a patriot and hero who fought in the name of liberty and justice, both in Europe and North America.

_______________________________________________________________________

Robert Ranstadler is a retired U.S. Marine and independent military historian who turned to freelance writing and editing after retiring from active duty service in 2015. He holds an advanced degree in history, has written multiple feature-length articles, and is currently preparing a monograph about irregular tactics and partisan warfighters in the Revolutionary War. Robert resides in Virginia where he and his family enjoy hiking and exploring historic battlefields across the Southeastern United States.