The HMS Medusa (A353) – formerly known as the Harbour Motor Defence Launch (HMDL) 1387 – was near Omaha Beach on June 5, 1944, the night before D-Day. Without the pinpoint accuracy of this tiny British ship, the massive Allied invasion force would have been compromised.

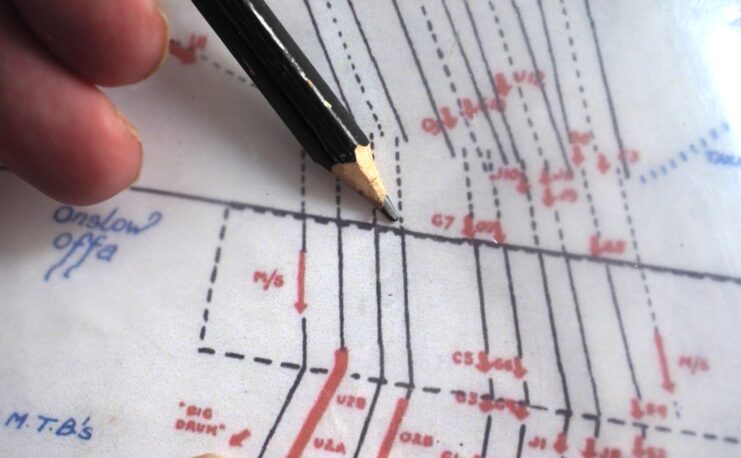

Setting off from Portland, the HMS Medusa was a Navigational Leader and a key marker on which the fleet tasked with landing on Omaha Beach honed in on, in order to hit the clear path through to Normandy. This 72-foot-long ship, manned by a crew of 10, had to hit a pre-ordained mark on a map set by the commanding officers of the large maritime invasion.

Ten days prior to the invasion, an ultrasonic beacon (FH 830) was placed on the seabed, so Medusa‘s crew would be in the correct location. It transmitted in Morse code the letter “D,” allowing the vessel to situate herself directly over it. This effort was aided by the ASDIC fitted to her that just listened, and as long as her crew could hear the “D,” they knew they were in the right place.

Fitted with then-secret and state-of-the-art Decca QM radio receivers, Medusa was able to locate the entrance, even during the very poor weather that pushed the invasion back 24 hours in 1944. The radios were so secret that the ship was fitted with pre-explosive charges, and if there were any fears of capture, then the ship would be blown up and sunk.

This system was so secret that the Germans were unaware of its existence, although they did jam a similar one used by the Royal Air Force (RAF).

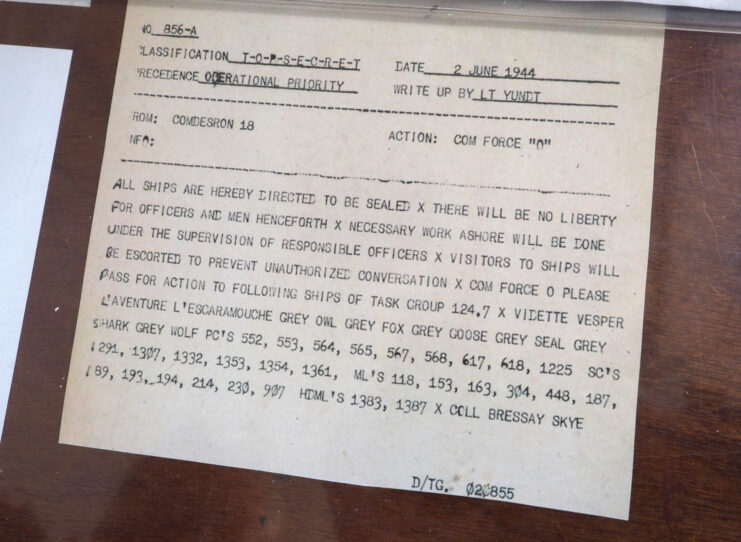

Once they were made aware of their mission, Medusa‘s crew were certainly of the opinion that this was potentially a one-way mission. In the build-up to June 5, the vessel was locked down and her crew unable to leave or communicate with anyone. The final battle orders were only inspected once at sea and well away from Portland, which is where they’d left from.

This was, of course, delayed due to bad weather, and Medusa and her crew were forced to sit out that extended period in the rough seas of the English Channel an extra day. Once in position, Medusa‘s crew sent out a radar pulse from her stern that the oncoming fleet could pick up secretly, allowing them to head safely to the ship and through the minefield to the invasion itself.

Without Medusa and her work, the whole invasion was at risk, as hitting the mines would have alerted the Germans as to where the forces were heading. This would have meant the deception plan that it was to be at Calais would have literally been blown out of the water.

The technology that made all of this possible was a series of three radio transmitters along the southern coast of England. These were detected by the secret receivers on Medusa, which then steered a straight line following the readouts on the radio receivers to the cleared entrance lane in the German minefield.

Today, the HMS Medusa is the only one of her type still at sea and pretty well in her original seafaring wartime specification. There have been one or two modern alterations, to comply with current maritime regulations. However, she’s a fully working seagoing HDML from the Second World War and a unique historical rarity.

Medusa‘s roles were designed to provide an offshore anti-submarine screen for harbors, but she was used for convoy escort, offensive operations, and agent landing and recovery. The ship herself is operated under the Medusa Trust, a charity focused around preserving and operating the ship for future generations.

It also aims to keep Medusa operational and at sea as an inspiration to the young, provides training days for Royal Navy cadets and Sea Cadets, and maintains and passes on the unique skills of operating a small ship, on top of serving as an enduring tribute to the veterans, recording the story of each of the 464 HDMLs and their crews.

Medusa also took the surrender of German troops on May 5, 1945 at IJmuiden, when she was sent to establish the damage to the port, which connects directly to Amsterdam. A few days later, she was in Amsterdam, so her crew could celebrate V-E Day.

The ship is currently moored at Haslar Marina in Gosport, Hampshire, and now makes trips from there, but mainly during the summer months.

Back in 1968, Medusa was close to being broken up at Plymouth when three people stepped in: Dave Bishop, John “Tug” Wilson and Mike Boyce. The trio found just over £3,000 and bought her by tender, with the idea that they’d bring her back into service. In the end, it took them around 18 years, with the team and other volunteers learning boat-building and skills along the way.

Much of the work was carried out in a boatyard at Ferrybridge, near where Medusa‘s first captain, Mike Boyce, lived in Portland. Once she was completed, the ship was a regular visitor to ports in England, France, Belgium and the Channel Islands. Some other highlights were taking part in events around the period of the 50th anniversary of D-Day in the United Kingdom and Normandy.

More from us: USS Gerald R. Ford (CVN-78): The World’s Largest and Most Advanced Aircraft Carrier

In late May 2012, the HMS Medusa sailed to London and was part of Her Majesty’s Diamond Jubilee Pageant, which was reviewed by Queen Elizabeth II as the vessels paraded past her and along the Thames, near the Tower of London.