Conflict often reveals unexpected qualities in people. Some who appear fearless may falter when tested, while those who seem reserved or unremarkable can display remarkable resilience. Again and again, it is the unconventional—the misfits and rule-breakers—who defy expectations with acts of exceptional valor. Maynard Harrison Smith fit that mold: considered difficult and unimpressive by many, until a single pivotal moment exposed the depth of his courage.

Maynard Harrison Smith’s early life

Maynard Harrison Smith was born on May 19, 1911, in Caro, Michigan, to a lawyer father and a schoolteacher mother. Though his upbringing wasn’t particularly harsh, Smith struggled socially and had a reputation as an outsider. Hoping to instill structure and discipline, his parents enrolled him at Howe Military Academy in Indiana.

As an adult, Smith found work as a tax field agent for the U.S. Treasury Department, but he primarily lived off his inheritance. He married for the first time in 1929, though the union ended in divorce just three years later. A second marriage followed in 1941, but it quickly unraveled the following year. That relationship produced a child—and ultimately, it would lead to legal trouble of Smith’s own making.

Two options: Go to jail or join the US Army

Following his second divorce, Maynard Harrison Smith was arrested for failing to pay child support. He appeared before a judge and was given a choice: going to jail or joining the US Army. To avoid jail, Smith chose military service.

At 31, Smith began basic training as one of the oldest recruits, harboring resentment toward younger officers whom he felt lacked experience. Believing that the US Army Air Forces (USAAF) offered the quickest path to advance his career, he volunteered for Aerial Gunnery School.

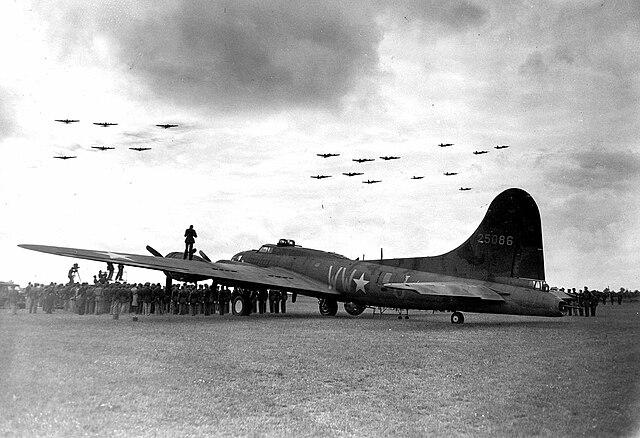

Smith’s small size made him well-suited for the confined space of a ball turret. After completing his training, he earned the rank of staff sergeant and was assigned to the 423rd Bombardment Squadron, 306th Bombardment Group, Eighth Air Force, where he served on a Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress.

Attacking the U-boat pens at Saint-Nazaire

Maynard Harrison Smith’s fellow airmen didn’t like him much and he was soon given the nickname, “Snuffy Smith.” He flew his first combat mission on May 1, 1943, which would be the first time the irascible, disagreeable aerial gunner would show his true colors.

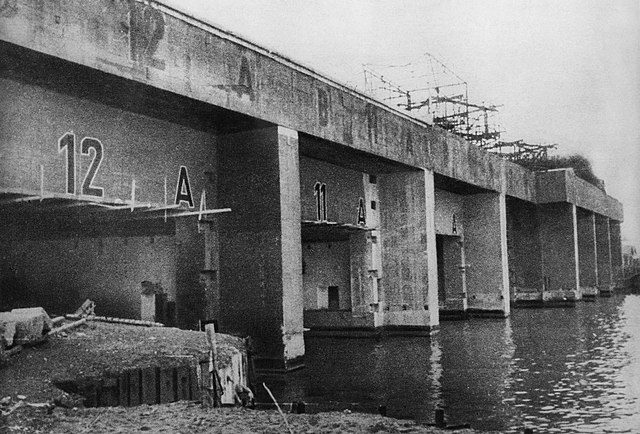

The target of the mission was the German U-boat pens at Saint-Nazaire, on France’s west coast. The location had been nicknamed “Flak City” by Allied airmen because of the heavy German anti-aircraft defenses that had been erected there.

The first part of the mission suffered issues, as many of the American bombers tasked with attacking the site suffered mechanical problems, but the middle portion went off without a hitch. After the B-17s had dropped most of their bombs, however, they were engaged by Luftwaffe fighters.

The American bombers fled into a large cloud bank to evade the Germans, and while this was successful as an evasive maneuver, it resulted in them flying well off course.

Fire aboard the Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress

When the lead navigator first sighted land, he mistakenly believed it to be the shores of Britain. Acting on that error, the pilot dropped the B-17 to just 2,000 feet. In truth, they were approaching Brest on the French coast. As the bomber emerged from the clouds, it was met with a sudden storm of enemy fire—flak exploding from the ground while German fighters swooped in from above.

Smith’s plane bore the brunt of the attack. Shrapnel from anti-aircraft rounds shredded a wing-mounted fuel tank, sending gasoline flooding into the cabin. Within moments, flames erupted, fanned into a deadly blaze by oxygen leaking from the damaged system.

Trapped in the powerless ball turret, Smith had to crank it by hand to free himself. Crawling into the main cabin, he found chaos: fire roaring through the fuselage, jagged holes in the aircraft’s skin, and crucial instruments smashed. Two crewmates were badly wounded, and fear was overtaking the rest.

In desperation, the radioman leapt from the bomber without a parachute. Moments later, two more crew members—choosing the uncertain sea over the inferno—bailed out, disappearing into the sky.

Maynard Harrison Smith takes control of the situation

Maynard Harrison Smith didn’t know if the pilot was alive or dead, or whether he’d bailed out of the burning B-17 like the other three had just done, but he did know that six crewmen with varying degrees of injuries remained and he wasn’t one to just stand there and let them burn to death.

As long as the B-17 kept flying, Smith decided he would do what he could to extinguish the flames, help out his injured comrades and fight off the Germans, who were still attacking the burning bomber. Wrapping himself in whatever protective clothing he could, he fought the flames first with fire extinguishers. When those were used up, he used bottles of drinking water and any other non-flammable liquids he could get his hands on.

Despite his best efforts, the fire continued to spread, and the flames were getting so intense in some areas that ammunition was starting to go off. Smith realized he had another task to take on single-handedly: toss the burning ammunition boxes overboard before they could explode.

Between throwing burning ammunition into the sea, tending to his wounded comrades and fighting an endless battle against the flames – for which he even used his own urine in desperation – the aerial gunner also manned two machine guns, fighting off the German fighters until they finally gave up and flew away.

At this stage, it was clear the B-17 was a write-off and their only hope was to land before it fell apart. Somehow, the pilot managed to achieve this and landed the almost-destroyed bomber on a British airstrip. A few minutes after landing, the B-17, riddled with 3,500 bullet holes and held together only by the four main beams of its frame, fell apart. The men were all safe, however, thanks to Smith’s heroic actions.

Maynard Harrison Smith was awarded the Medal of Honor

For his immense courage, Maynard Harrison Smith was awarded the Medal of Honor, becoming the first enlisted airman of the US Army Air Forces to receive this distinction.

When the time came to award him with the medal, however, he was nowhere to be found. Eventually, he was located scraping leftovers from breakfast dishes, having been assigned this duty as a disciplinary measure. It was ultimately presented to him by Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson at the Eighth Army Airfield in England.

Following his gallantry in the skies, Smith flew four more combat missions, before being grounded for combat stress reaction. He was subsequently assigned to clerical work, which he was less than adequate at – his poor performance led to him being demoted to the rank of private.

He returned Stateside in February 1945 and was discharged a few months later. On top of his Medal of Honor, he was awarded the USAAF Enlisted Aircrew Badge, the Air Medal with Bronze Oak Leaf Cluster, the American Campaign Medal, the European-African-Middle Eastern Campaign Medal with four Bronze Campaign Stars and the World War II Victory Medal.

Maynard Harrison Smith’s later life

Shortly before the close of the Second World War, Maynard Harrison Smith married his third wife, with whom he had four children – three sons and a daughter.

While he initially ran into legal troubles during his re-entry into civilian life, Smith did manage to make a comfortable living. Following his retirement, he moved to Florida. He passed away from heart failure on May 11, 1984, at the age of 72.

More from us: Was the Allied Bombing of Dresden a War Crime or Wartime Necessity?

Like so many veterans, he was interred at Arlington National Cemetery.