Operation Downfall

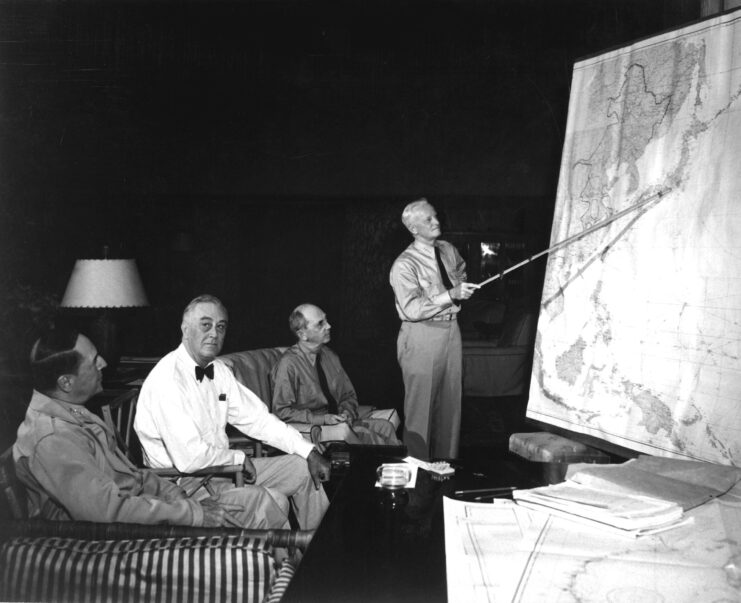

Operation Downfall was the U.S. military’s detailed plan to invade and defeat Japan, and it was set to be the largest amphibious invasion in history—surpassing even D-Day. The plan had two main parts: Operation Olympic and Operation Coronet.

Olympic was scheduled to launch in November 1945, targeting the southern island of Kyūshū. Once captured, Kyūshū would be used as a base to support Coronet, the second and even larger phase. Coronet was planned for March 1946 and aimed to invade the Tokyo Plain.

The invasion never happened. Japan surrendered after the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, along with the Soviet Union’s declaration of war. As a result, the U.S. called off Operation Downfall, avoiding what likely would have been a devastating loss of life on both sides.

Training kamikaze frogmen

To get ready for the expected Allied invasion, the Japanese came up with the Fukuryu tactic as a defensive plan. The name means “crouching dragon,” and it used specially trained suicide frogmen to launch surprise underwater attacks on enemy ships.

The idea was first proposed in 1944 by Captain Kiichi Shintani from the Anti-Submarine School at Yokosuka Naval Base in Japan. With Japan’s usual defenses growing weaker due to a lack of people and supplies, Shintani looked back at earlier battles, like Peleliu, for ideas.

These frogmen were placed underwater at important spots along Japan’s coast, ready to blow up enemy ships at night. Because they moved underwater, they were hard to see, making it tough for enemy forces to find or stop them.

Fukuryu attacks

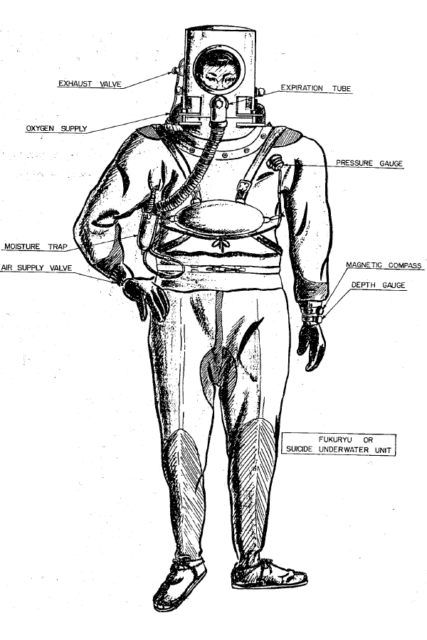

Kamikaze frogmen would emerge from their underwater hideouts wearing diving suits, carrying 16-foot bamboo spears tipped with Type-5 attack mines. Each mine contained 33 pounds of explosives, designed to detonate on contact with the hulls of enemy ships above.

To aid their missions, additional explosives were strategically placed around their underwater stations. These operations were grim, as success meant certain death. The frogmen not only faced the reality of a one-way mission but also endured long, lonely hours waiting for the enemy to arrive.

Training the kamikaze frogmen

Extensive preparations were made to train train 6,000 kamikaze frogmen, each requiring specialized equipment. They were to wear full diving suits—jacket, pants, shoes, and helmet—and carry oxygen supplies and liquid food to survive about 10 hours underwater. To stay submerged at depths of 16 to 23 feet, each man also carried 20 pounds of lead to fight buoyancy.

Beyond equipping the divers, Japan planned to build hidden underwater shelters where they could lie in wait for enemy ships. One idea was to build large concrete structures on land and later sink them into place, but this plan was never carried out. Another idea involved steel underwater foxholes, but it was quickly scrapped due to the risk of disturbing nearby explosives.

Even with all the detailed planning, Japan’s kamikaze frogmen were never actually used in combat.

A failed initiative

The 71st Arashi were trained at Yokosuka, while the 81st Arashi would undergo training at Kure. Another unit was in the works at Sasebo. However, there were only two battalions fully trained by the time the Japanese surrendered, both with the 71st. The total equaled about 1,200 of the proposed 6,000 frogmen.

Training wasn’t the only thing falling behind, as production also proved difficult. Only 1,000 diving suits were ready at the time of surrender, and none of the real mines were constructed, only dummy ones.

Even though the Fukuryu were never used in combat, many still died during the training. Most of these fatalities were caused by issues with the breathing apparatuses in the diving suits. They were rudimentary, so each diver had to inhale through their nose and out through their mouth into a tank, which would turn the carbon monoxide back into oxygen.

If they mixed the two up, they’d inhale caustic lye and faint while underwater. If any seawater got into the tanks, a mixture was created that, when inhaled, would burn the lungs.

Other divers died when they got tangled in plant life on the ocean floor and were unable to free themselves. Ultimately, no enemy combatants were ever killed in Fukuryu attacks, yet so many trainees were that “they couldn’t keep up with cremation.”