A witty response or remark – also known as a “bon mot” in certain circles – takes a lot of spontaneous smarts to pull off.

But coming up with a succinct retort in the pressure-cooker circumstances of war — that takes skill.

Napoleon Bonaparte was rampaging all over Western Europe, claiming it as his own, in the early 19th century. He came up against a leader in Spain who would answer his aggression with action and some clever words.

General Jose de Palafox y Melci was a leader in the Zaragoza region. A huge chunk of Spain was already under Bonaparte’s thumb by 1809, but the Peninsula War was still in full swing between the two powers.

Palafox, badly outnumbered by “the little corporal,” had virtually no hope of winning this conflict. The French offered terms for surrender, to which Palafox responded “War to the knife!” meaning he’d fight to the very end.

Clearly, the fiery Spanish general was not about to be pushed around.

He may have been too proud to surrender, but it cost him – and his people. Historians estimate that 50,000 soldiers (both Spanish and French) died in the conflict, and Palafox was ultimately taken prisoner.

When political or military leaders stand in defiance against an enemy, it inevitably costs the nation’s people dearly. And when it came to the Axis powers of World War II – Germany, Italy, etc., — Greece paid a hefty price for its defiance.

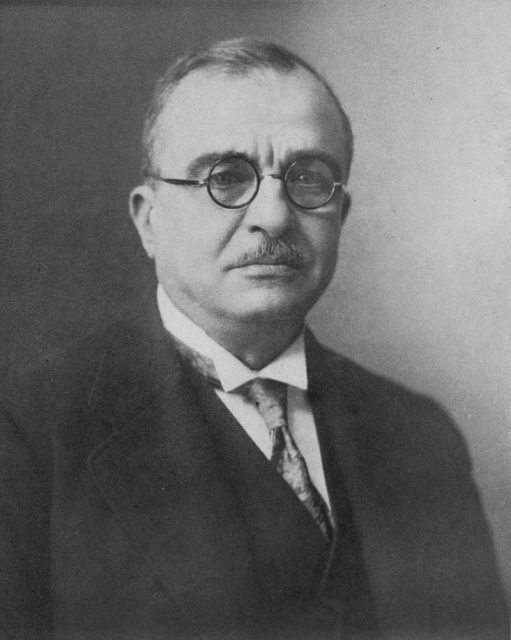

The Greek Prime Minister at the time, Ioannis Metaxas, was elected in 1936.

His reputation in history is marred by his leanings toward fascism. Having watched its rise in Germany and Italy, he began running Greece in an authoritarian manner.

Nevertheless, when an Italian official came calling in October 1940, insisting that Greece surrender to Italy, Metaxas had a simple, uncompromising response: “Alors, c’est la guerre” (“Alas, then it is war”).

The Italians were not amused and promptly invaded. They were unsuccessful in their campaigns, but Germany came to their assistance, capturing Athens in April 1941.

But Metaxas’s stand is still remembered fondly in Greece. Every October 28th, the country celebrates “Ohi Day” (“No Day”).

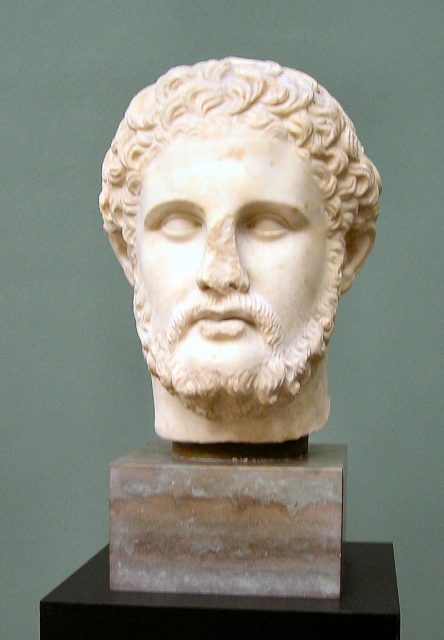

That was not the first time the Greeks had a war of words – and more – with an enemy.

In 480 B.C., the Persian Army rode into Greece in vengeance for the Greco-Persian War. But Spartan troops, though vastly outnumbered, stood their ground against the onslaught.

Historians agree that the massive Persian force was as many as one million strong. Nonetheless, when they sent word to the Spartans that they should lay down their weapons, the Spartans replied, “Come and take them.”

They fought for three long days, during which time the Greek Army time to fortify itself. The Spartans were ultimately defeated.

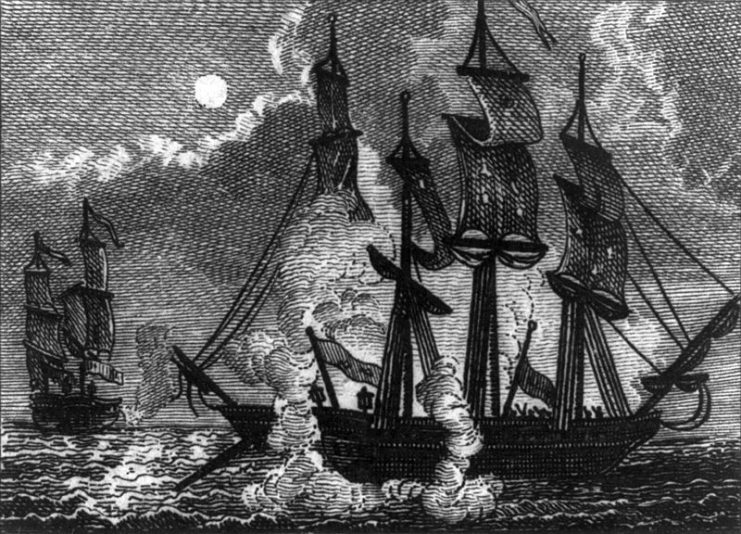

Some military responses have become famous for their phrasing, like that of John Paul Jones, a man thought to be the “father” of the United States Navy.

While commander of the USS Bonhomme Richard in 1779, Jones and his crew were sailing in the North Atlantic when his ship met two escorts of the Baltic merchant fleet: the HMS Serapis and the Countess of Scarborough.

Jones took on both ships, and his vessel was badly damaged.

But Jones didn’t care. When asked if he was surrendering his damaged ship, he uttered the famous line: “I have not yet begun to fight!”

The battle continued for another three hours, and in spite of the odds against him, Jones took control of the HMS Serapis, while the British Navy watched in a kind of stunned silence. (His own ship, the Bonhomme Richard, sank).

Some military leaders, like Jones, rise to the occasion when the stress of battle is at its peak. That’s true of Brigadier General Anthony McAuliffe, who led the 101st Airborne in Belgium during World War II.

After the invasion at Normandy, the Germans had little left to fight with. Still, they managed to launch a massive assault near Antwerp of almost half a million soldiers, which caught the Allies off guard.

McAuliffe took his men back to the Belgian town of Bastogne, but would not retreat any further. When he got word that his men were outnumbered 5-1, all McAuliffe could say was, “Nuts.” It must be the greatest military understatement of all time.

While he pondered what to do next, reinforcements arrived, led by General George Patton. Patton was famous for his acumen on the battlefield, and this one didn’t disappoint.

In a wildly, unlikely-to-win strategy, the two leaders launched another attack on the German troops and forced them back toward Berlin. It’s considered one of the most brilliant and clever tactical maneuvers of the war.

Read another story from us: Life of General Patton in 50 Pictures

Whether grand, wildly optimistic or just plain wishful thinking, these comebacks have gone down in history for their bravery, their wittiness, their cleverness, or a combination of all three.

Who knows how these men came up with such brilliant remarks on the spot, but history has taken notice. Being remembered for words, as much as deeds, is a remarkable achievement in wartime.