As Emperor of the French, Napoleon Bonaparte would conquer half of Europe and leave the rest trembling in terror at his approach.

But the rise of Napoleon didn’t initially come from conquering foreign nations, or the sort of imperial majesty that the title ‘Emperor’ implies. Far from it, Napoleon’s battles were at first against his fellow Frenchmen, as he sought to defend the republican government he would later destroy.

Origins of an Officer

Born on 15 August 1769, Napoleon Bonaparte was the fourth child of minor Corsican aristocrats. Admitted to a military academy at Brienne-le-Château at the age of nine, he was destined for a military career from an early age. He excelled at mathematics, a skill that would prove useful for his future career as an artillerist.

Graduating in September 1785, he became a second lieutenant in an artillery regiment. At the time, the most remarkable thing about him was his Corsican nationalism, and he took two years off early in his career to spend time at home. It was with the coming of the French Revolution in 1789 that Napoleon’s career really took off.

Leading a unit of volunteers for the Jacobin Republicans in Corsica, Napoleon made a good impression, and in July 1792 he was promoted to the rank of captain in the French army.

A year later, he wrote a pamphlet endorsing the Republican cause, winning him the favour of Augustin Robespierre, whose older brother Maximilien was one of the most powerful revolutionary leaders.

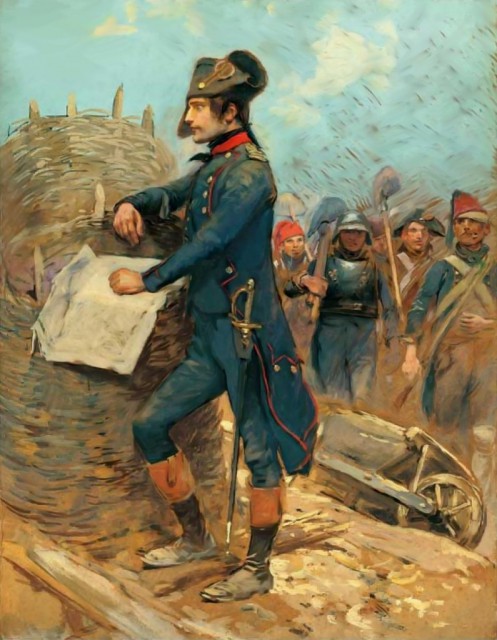

And so Napoleon was given his most important position so far – commander of the government artillery at the Siege of Toulon.

The Siege of Toulon (8 September – 19 December 1793)

Toulon, like many other cities in southern France, was dominated by royalists. As the liberating impact of the French Revolution gave way to waves of repression, these royalists rose up in revolt against the government. Supported by the British and the Spanish, they hoped to overthrow the republic and restore the French monarchy.

As a major arsenal for the French navy, Toulon had great importance, and could not be allowed to stay in enemy hands. Without the use of the city, the Republicans would be less able to defend their country from outside attack, never mind repress the royalist counter-revolution. And so they swiftly besieged the city.

British forces had been committed to defending Toulon, and they set up fortifications around the town. This made artillery even more vital if Toulon was to be taken.

Napoleon rose to the challenge. With energy and determination, he gathered a hundred fresh guns from wherever he could, including other French forces in the area. Without enough artillerists to operate them, he trained infantry in their use. Soon the bombardment was falling thick and fast on Toulon.

Further batteries were assembled and put into action up to 14 December. In response, a British sortie seized one these batteries, and Napoleon headed the counter-attack that retook it.

It was on the night of 16 December that Colonel Napoleon would prove himself. One of three officers leading an assault on the British and royalist positions, he was involved in the thick of the fighting and was stabbed in the thigh with a British bayonetted.

Though he was out of action when Toulon fell three days later, this was effectively Napoleon’s first victory. His strategic planning, his tireless assembly of artillery batteries, and his courage in the night assault, all made a huge contribution to a significant victory against both the royalists and the foreign invaders backing them.

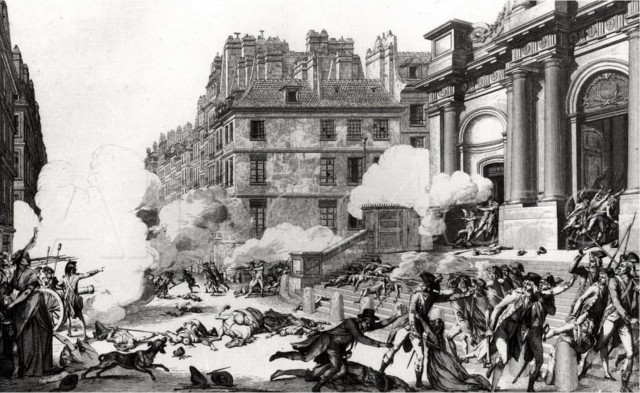

13 Vendémiaire (5 October 1795)

It was a far less grand battle, but an equally important one, that took Napoleon from celebrated officer to commander of entire armies. This was the action of 13 Vendémiaire Year 4 in the Republican calendar.

Two years on from Toulon, the French government was still plagued by internal power struggles and royalist uprisings. By October 1795, a royalist army was marching toward Paris, and citizens of royalist districts rose up in revolt, taking control of the area of the city known as Le Peletier.

The National Convention, which governed France at the time, realised that it was in danger and so summoned an improvised army of patriots, as well as calling in the National Guard. Initial attempts to quell the uprising on 12 Vendémiaire failed, and there was a danger that more people would join the royalist cause.

At this point, General Napoleon Bonaparte arrived at the Convention. He offered his assistance on condition that he was given complete freedom of action, and the terrified politicians readily accepted his terms.

Around one in the morning on 13 Vendémiaire, Napoleon decides to override the orders of the men commanding the Convention’s forces, and who had proved so ineffective until now. Sending a cavalry unit to retrieve a set 40 cannon from elsewhere in Paris, he assembled them in front of the royalist route of advance.

When the royalists attacked at ten in the morning, they outnumbered the Republicans six to one. But Napoleon’s careful positioning of the guns allowed him to bombard the attackers with canisters of grapeshot at close range, driving them back.

Over two hours of fighting, he defeated the royalists, leaving hundreds dead and their revolt in tatters. His horse was shot from underneath him during the fighting, but he emerged unscathed.

Historian Thomas Carlyle would later say that, on 13 Vendémiaire, Napoleon won with a whiff of grapeshot and in doing so effectively ended the French Revolution. Though the Convention lived on, he now had the fame and authority to take command of the French Army of Italy, and from there to take over the country.

From a humble start fighting for the republic, Napoleon created his chance to overthrow it.