Napoleon’s 1796 invasion of Italy was one of the most significant campaigns of his career. It was the offensive that turned him from a rising star into a commander with an unassailable reputation for excellence. It began a string of French victories and Napoleon’s rise from leading an army to leading a nation.

Old Tools, New Tactics

The army with which Napoleon waged war in Italy was the same as that of pre-revolutionary France. Similar weapons, unit organization, and drill manuals were implemented. The forces that met in Italy were little different from those of the Seven Years War.

What was different was the way in which Napoleon fought. He moved with surprising speed around the Italian Peninsula. His troops arrived long before their opponents expected them. On the battlefield, he showed a swiftness, decisiveness, and flexibility his opponents could not match.

It was this that made Italy his proving ground.

Into Italy

When Napoleon invaded Italy in the spring of 1796, it was not a united country. The peninsula consisted of a series of city-states, including the sovereign territory of the Pope. The Austrians dominated the region, through both direct rule and their powerful political influence on, theoretically, independent powers.

The French Army of the South, given to Napoleon for this campaign, was 37,000 men strong. Those troops were poorly fed and close to mutiny. The power of Napoleon’s personality and the successes he brought turned an army near breaking into one swelling with pride.

They faced a challenge, outnumbered by the Austrians and their allies by at least 15,000 men.

Montenotte and Piedmont

The first significant action in Italy came at Montenotte on April 12. Napoleon blocked a pass then lured an Austrian force in by having part of his army retreat. He then attacked them in the pass with a superior force, routing the Austrians, preventing them from joining up with their Piedmontese allies.

Moving quickly, he defeated the Piedmontese at Millesimo, the Austrians at Dego and Ceva, and the Piedmontese again at Vico. His enemies retreated to defensive positions.

Rather than face further losses, the Piedmontese surrendered. In a matter of weeks, Napoleon had knocked them out of the war.

Lodi

Maneuvering around Austrian forces, Napoleon headed for Milan. It was on his way there that the next significant action came, against the Austrians at the Bridge of Lodi.

Only 12 feet wide, 200 feet long, and overlooked by a battery of Austrian guns, the Bridge was a nightmare to cross. Napoleon sent his cavalry in a flanking maneuver, looking for an easier crossing of the river, while he began an infantry assault to keep the Austrians occupied.

It almost ended in disaster. French troops took devastating fire from the guns, some men diving into the river to avoid being shot. As they reached the opposite bank, the survivors were charged by Austrian cavalry.

Just in time, the French cavalry arrived, having completed their flanking operation. Surprised and out-manoeuvred, the Austrians were soundly beaten.

Napoleon took Milan.

The Heart of Italy

Under orders from the French Government and eager for spoils with which to pay his men, Napoleon moved on to central Italy. There the Pope gave him a collection of artistic treasures to stop him attacking the Papal States. Another Austrian force was sent, only to be outmaneuvered and defeated by Napoleon at Lonato.

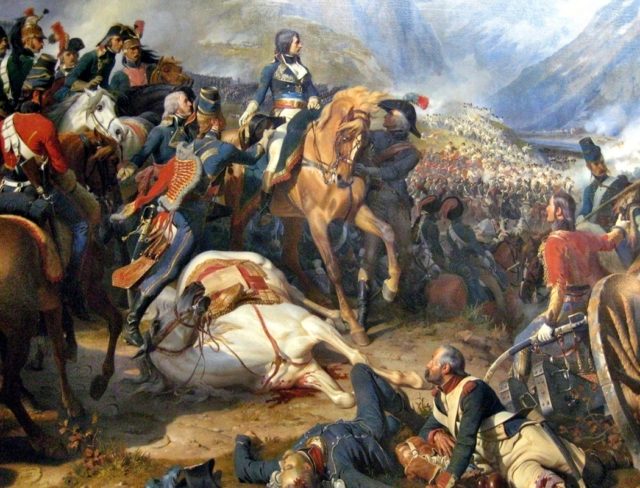

Arcola

Following successes against the French on the Rhine, the Austrians freed some troops to send against Napoleon. He suffered his first defeat in Italy outside Verona on November 12 and wondered if Italy might be lost.

Within days he had made up for this at Arcola. In an attack (later made famous by French artists) he led his men in a charge across a bridge, hoping to recreate the success at Lodi. When it failed, he moved his army south, had pontoons built across marshy ground, and out-flanked the Austrians. Both sides took heavy casualties, but the victory was Napoleon’s again.

Rivoli

The war dragged on through the winter. A series of small engagements incurred casualties on both sides and did nothing to help the Austrians recover. Finally, at Rivoli in January 1797, Napoleon defeated the Austrians one last time. Their forces were scattered, and the fortified town of Mantua fell. 30,000 Austrian soldiers surrendered to the French.

A General’s Peace

Although Napoleon had defeated his opponents, the Austrians still refused to make peace.

Not so the Pope, who recognized that he was at Napoleon’s mercy. Signing a treaty at Tolentino, he promised not to assist the Austrians in their fight against the French. At last, in April 1797, the Austrians came to the table.

What followed was one of the most important peace negotiations of history. Rather than hand over the discussions to politicians and diplomats, Napoleon himself negotiated a treaty with the Austrians. Inspired by examples such as Julius Caesar and Oliver Cromwell, he wanted to be a national as well as a military leader. This was part of that role.

The Austrians made substantial concessions on both the Italian front and their northern European territory. Belgium, Holland, and the west bank of the Rhine became French. The Cisalpine Republic, a satellite state cobbled together by Napoleon from lands that had belonged to the Austrians, was recognized as independent by its former overlords.

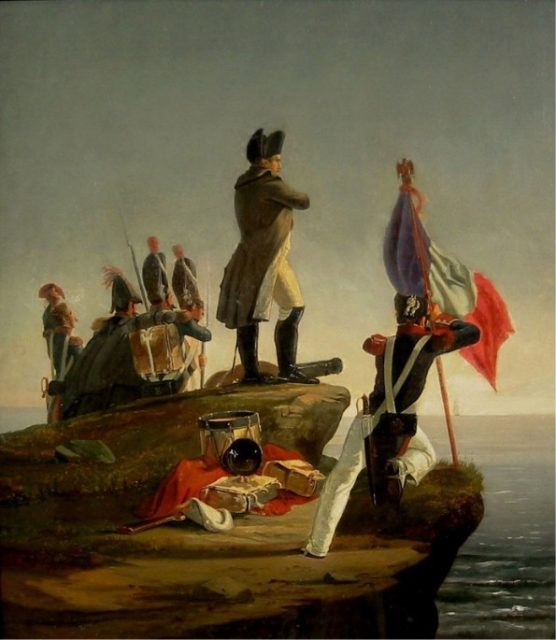

Building a Legend

Throughout all, Napoleon worked on spreading the news of his greatness. He commissioned two newspapers to celebrate his successes both within the army and at home. He sent regular updates to Paris and had pieces published in the press there. He commissioned artists to celebrate his achievements.

Napoleon’s Italian campaign was a great success. Through his telling of the story, Napoleon ensured it would become an even more glorious one.

Sources:

Alan Forrest (2011), Napoleon.

Robert Harvey (2006), The War of Wars: The Epic Struggle Between Britain and France: 1789-1815.