Fought on June 18, 1815, the Battle of Waterloo was one of the most decisive encounters in European history. The final defeat of Napoleon ended his dreams of empire and created a new balance of power in Europe.

Napoleon’s Return

After two decades of leading France to military glory, Napoleon Bonaparte was defeated in 1814. Allied armies advanced into France from the east and the south. Faith in Napoleon’s leadership collapsed. Faced with the hostility of their powerful neighbors, the French gave up on their emperor in return for peace.

By the following year, the situation had changed. The restored Bourbon monarchy threatened the future of the liberals and middle classes. Many were yearning for the return of imperial glory.

When Napoleon returned from exile, men swiftly rallied to his cause. Even those sent to arrest him joined his side. He gathered a large army and marched east, ready to show his opponents his strength.

Preludes

Two great opponents faced Napoleon as he marched into the Low Countries.

One was Marshal Blücher, the respected commander of the Prussian Army. Over the previous one hundred years, Prussia had emerged from a fragmented mass of German principalities as the strongest with one of the most disciplined armies in the world.

The other was the Duke of Wellington. Over seven years of fighting in the Spanish Peninsula, Wellington had proven his worth as a general and demonstrated the strength of British infantry.

On June 16, two separate French forces clashed with those armies. At Ligny, Napoleon defeated the Prussians. At Quatre Bas, the French under Marshal Ney fought an indecisive battle against Wellington’s British and Dutch force.

Two days later, French forces were still holding the British and Prussians apart. Napoleon lined up the bulk of his army facing Wellington across a valley near Waterloo.

The decisive moment had come.

Hougoumont: The Battle Begins

The battle began around 11:30 in the morning. French artillery bombarded the chateau of Hougoumont, held by British troops led by James Macdonald. Napoleon’s brother Jérôme then led a fierce attack against the position.

Over the course of the day, the outer walls of the chateau fell, and its roof was set on fire. Macdonald and his outnumbered men fought on. The chateau was held.

Cavalry

Following the indecisive initial fighting, Napoleon ordered an attack on the British center around La Haye Sainte. He hoped to break the British before the Prussians arrived.

Marshal Ney, believing the British were in retreat, led his cavalry in a massive uphill charge. The British infantry formed into squares, allowing them to withstand the attack. British cavalry led by Uxbridge then counter-attacked, driving back Ney’s forces.

A dozen French cavalry charges followed. Each time, the British formed squares and withstood the assault, relieved at a break from artillery fire.

Meanwhile the Prussians…

Marching toward the sound of battle, the Prussians had run up against the village of Plancenoit. The French had heavily fortified the village to their rear, enabling it to hold out against the Prussian army for five hours.

For most of the afternoon, the Prussians struggled to overcome French opposition and clogged roads. Despite their absence from the field, they played an important part in the battle. Napoleon was under pressure from their impending arrival and forced to divert forces to hold them off.

La Haye Sainte

Napoleon had always been a master of artillery. His use of cannons was taking a toll on the British lines.

British forces were particularly strained in the center. At La Haye Sainte, Hanoverian troops were under pressure from Ney’s attacks. An organizational failure had left them without replacement ammunition, and Wellington was spread too thinly to send reinforcements. Eventually, following a last-ditch counter-attack, they had to give up their positions.

Unknown to them, it was just as bad for Ney. He was running out of men. Napoleon refused to send more. The battle hung in the balance.

The Imperial Guard Advance

By half past seven in the evening, it looked like the French would win. Prussian forces were arriving on the British flank but only in limited numbers. As the sun began to sink through a smoke-clouded sky, Napoleon made his last bold move.

The Imperial Guard, held in reserve throughout the battle, advanced on the British lines. As the French approached across open ground, the British infantry emerged from shelter behind the ridgeline. A force under Sir John Colborne advanced around the flank.

With impeccable discipline, the British opened fire from two sides at close range.

For the first time in their history, the Imperial Guard retreated.

The British Advance

Wellington waved his hat in the air. At this pre-arranged signal, British reserves advanced to attack in the center.

For a moment, the battle still appeared to hang in the balance. The Guard’s retreat halted briefly, due to cavalry support. French troops could see the Prussians were joining the British. They were being pushed back by the redcoats pouring down the hillside.

The French army went into full retreat. A small force of Imperial Guard formed to protect Napoleon. Plancenoit had fallen, leaving the Prussians free to advance from the rear. It was useless to try to hold the field.

As the French streamed away, Wellington called off the pursuit and let his exhausted men rest.

Aftermath

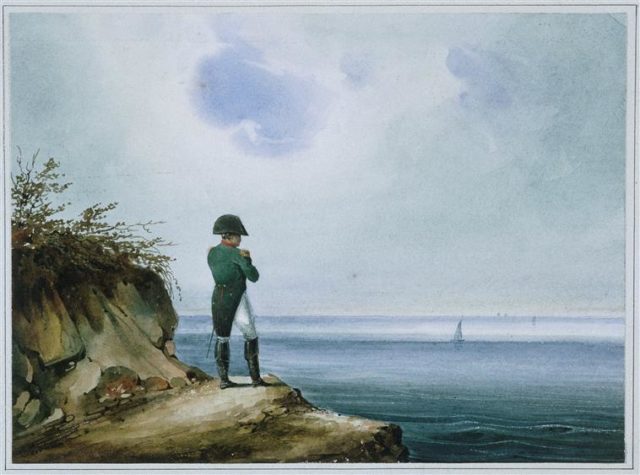

As the Prussians slaughtered the retreating French at Genappe, Napoleon was escaping. He had been defeated, and there would be no second comeback.

Napoleon spent the rest of his life in exile. Wellington became British Prime Minister. Prussia consolidated its position as the leading power in Germany.

The Emperor of France had overstretched himself and finally fallen.

Sources:

Robert Harvey (2006), The War of Wars: The Epic Struggle Between Britain and France: 1789-1815

John Keegan (1987), The Mask of Command