In 1981, a film was released which is still cited as one of Germany’s greatest cinematic triumphs. It followed the exploits of U-96, a German submarine, based out of St. Nazaire, France, on the harrowing experience of U-Boat patrol. The film is, of course, Das Boot, and its incredible ability to capture the terrifying and suspense filled life of U-Boat crews has captivated viewers for decades.

The film, along with the book by the same name, was based on a true story, recorded by Lothar-Günther Buchheim. He joined the Kriegsmarine, the German Navy, in 1940, eventually becoming a propaganda officer, essentially a war correspondent.

The film, as Buchheim complained, was not always an accurate portrayal of U-Boat life. Rather than go scene by scene picking apart the movie, here are a few stories of U-Boat life from the man who served on U-96.

Periscope Attack

It is a calm, but foggy day in the Atlantic. U-96 is sailing along, bobbing in the choppy seas, the commander and Buccheim are sitting down to lunch, a brief break in the daily stress of U-boat life.

Suddenly a call comes down from the bridge “To the commander: masthead off the port bow!”

The commander sprints up to the bridge. He and the chief crowd onto the bridge tower, straining through binoculars to find their foe.

They are puzzled. It appears to be a lone steamer, unescorted in the middle of the ocean. They estimate distance, direction, and speed, the latter by trying to match it. Their diesel engines strain, pushing the ship to its fastest and filling the entire ship with a dull roar as they plow through the choppy sea.

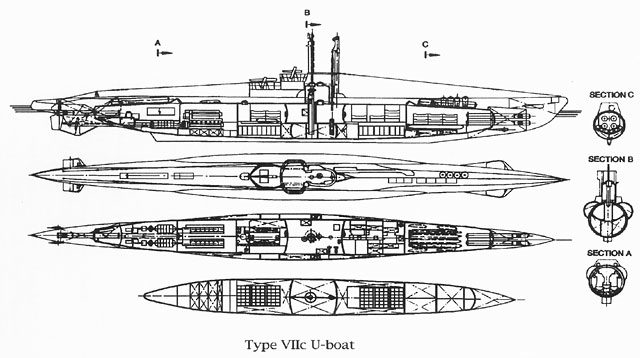

Satisfied with their readings, the commander orders an attack. The call goes out to clear the bridge, flood the tanks, and dive to periscope depth. The crew has been standing by, tensely waiting to hear the order. It echoes fore and aft, each man passing it down the line. The ship jumps to life. The diesel engines are secured, the electric motors hum to life and then the ship is quiet again.

In the control room, the commander and chief hover over the hydroplane operators, watching dials, hand wheels, and gauges. The ventilators are turned off, and moisture builds up on every surface, including the men who are now drenched in sweat.

Periscope depth is achieved, The commander peers through the thin tube, with mirrors and magnifiers. A watch officer is constantly adjusting the torpedo’s guidance. Again, everyone is silent, tensely waiting for the commander’s orders.

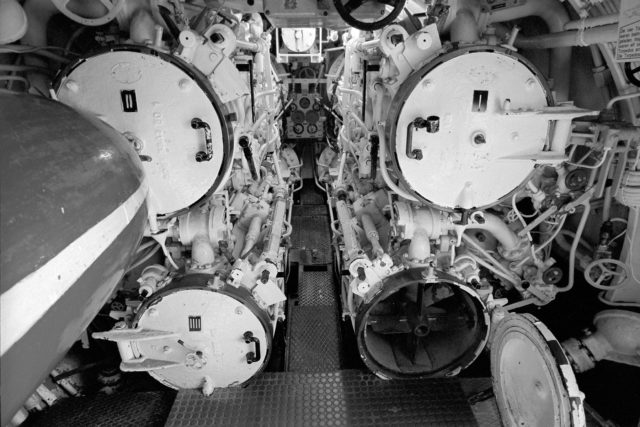

“Tubes 1 to 4, stand by for underwater firing. Flood tubes. Open torpedo doors!” The call, again, echoes through the ship. This time a response comes back. The order had been completed, all clear and ready for attack.

The crew stands silently watching their leader move back and forth with the periscope. He swears. The ship is zigzagging, making it a difficult target. After minutes of waiting, finally, he has his opportunity. The call goes out.

“Tube 1!” A pause, the watch officer’s finger hovers just over the firing button. “Fire!”

The sleek metal torpedo explodes out of the tube, speeding almost silently towards the ship. The commander calls for Tube 2. Now two torpedoes, parallel, are charging towards their target. Immediately the chief floods the tanks to compensate for the loss of weight; every kilogram counts when keeping the ship safely submerged.

They surface to survey the damage.

The lone steamer had been cut in two by the torpedoes, each half floating away from each other, the crew trying to get into lifeboats. Over the next 2 hours, the two halves slowly sank while the U-Boat crew watched.

Surviving a Depth Charge

A hydrophone sound is reported. Screws, turbine engine, likely a destroyer. The U-Boat dives and pulls away.

Surfacing, with the dark sky behind them, they determine that the destroyer, an American Wickes Class, is sitting near a destroyed ship, waiting for the sub to return. The U-Boat’s diesel motors start up.

Suddenly the destroyer turns and approaches the submarine. They dive, holding still underwater.

The sub resurfaces after an hour. The destroyer is still by the wreck, silhouetted by the flames of burning fuel. The submarine sits stationary, silently watching from the shadows.

After 3 hours the sub dives again, attempting to finish off what is left of the steamer. The destroyer spots them and again heads straight for them.

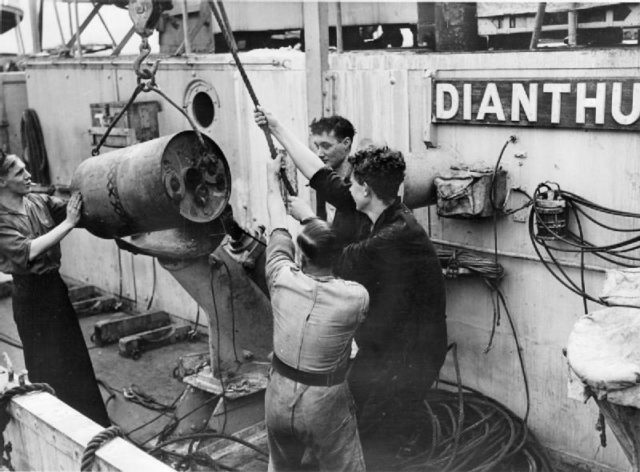

Alarm dive! The sub’s nose swings down into the murky depths of the Atlantic. They dive to 160 meters, then level off. Three explosions are heard overhead, then the destroyer’s propellers. The entire crew sits silently. Suddenly the propeller’s engines stop. They are sitting almost immediately above the submarine. Listening.

More depth charges, this time closer. Paint chips fall from the ceiling. The food bags and sausages hanging about the ship shake and sway back and forth as the vessel rocks. The commander orders evasive action. As the sub swerves, rises, falls, turns, and changes acceleration the destroyer continues to sweep overhead. The crew sits patiently, each explosion rattling them and their ship even more.

Sonar pings echo through the waves. The destroyer knows exactly where they are.

More depth charges. Everything goes black. The lights have been knocked out. A low call is heard “leakage above the water gauge,” and the control room erupts into a silent panic.

The commander calms his crew with the simple word “Gentlemen!”

Leaks spurt out across the ship, the commander seems unfazed, but the crew grows nervous. They cannot pump out the water with the destroyer overhead. The noisy pumps would give away their position, and they would be immediately destroyed. All nonessential lights are turned off, to save battery power.

They sit silently and still waiting for more depth charges or the horrific crushing death of sinking to the bottom. Water is still coming in through the leaks.

The commander requests a bearing on the destroyer. No response.

Annoyed, he requests again. Still no response.

He realizes what it means. The soundman is not ignoring him; the destroyer has stopped. No sonar pings, no depth charges, no propeller noise. Just silence. The sub’s electric motors push it forward underwater for another half hour. The commander leans against the hull and relaxes. They survived.

These two stories help to give a more accurate picture of U-Boat life. Das Boot, while a terrific film and a great piece of drama, is just that. They had to sacrifice some accuracy for dramatic effect. The movie lasts between 150 and almost 300 minutes. It is almost impossible to condense the incredibly long, tense, and terrifying life of U-Boat combat into a picture.

The U-Boat war was one of long hours. Crews sat and waited, silently, until they were certain they were safe, their prey destroyed, or their pursuer gone.

I encourage everyone to read Das Boot, (The Boat) and U-Boot Krieg (U-Boat War) by Lother-Guenther Buccheim, on whose accounts the film Das Boot was based.