“Be satisfied with the booty and the captives; the buildings and city belong to me.”

Those were the words spoken by Ottoman Sultan Mehmed II to one of his marauding soldiers drunk with victory. The blood-crazed Turkish warrior was in the process of desecrating the ornate marble flooring in the building that housed the once proud seat of the mother church of Eastern Christendom and the home of the Ecumenical Patriarch.

Sultan Mehmet II had been staring at the largest dome in Europe for 53 days from across the Sea of Marmara, and, finally, on May 29, 1453, it was his.

Roman Emperor Justinian built the Cathedral of Hagia Sophia nine hundred years before Mehmed’s boots walked across the golden mosaics of Jesus Christ. One of Mehmed’s first acts as the city’s new ruler was to convert this building of Christ into the Mosque of Aya Sofya in honor of Allah.

The victorious sultan had achieved the impossible. He was now master of one of the greatest cities in all of Christendom — some even claimed that it outmatched the splendor of the Eternal City of Rome.

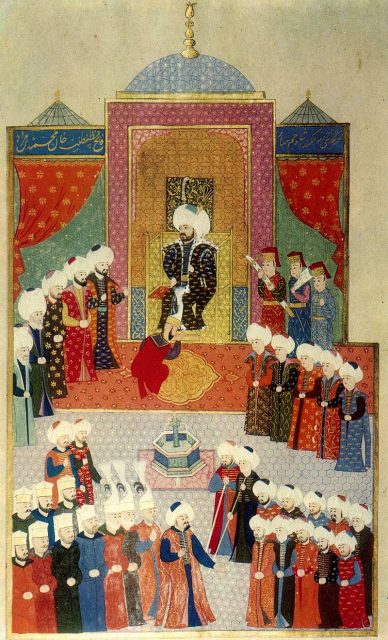

Mehmed II was highly intelligent and spoke six languages––even as a boy he dreamed of conquering Constantinople

His time came with the death of his father, Murad, in 1451. The then 19-year-old Mehmed II almost immediately announced his plans. He claimed that he was in the divine service of Allah and that Constantinople must fall. In the summer of that same year, he began his preparations for the siege.

The young sultan knew that the city’s mighty 12-mile long walls could only be breached by artillery. At the time, the Ottoman army had very little knowledge of cannons, the technology still being in its infancy.

One year after his father’s death, Mehmed succeeded in bribing a Hungarian engineer named Orbán to work for him. The expert cannon manufacturer had previously offered his services to Constantinople but had been turned down due to cost.

Orbán produced several huge bronze cannons for his new master. The largest was 30 feet long and shot a ball weighing in excess of half a ton across a distance of more than 1,600 yards.

The rest of Europe looked on in silence as the warriors of Islam rattled their scimitars

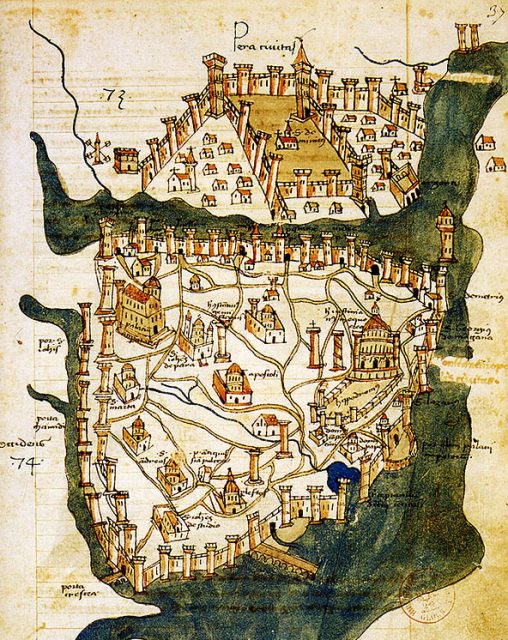

The former city of Byzantium or Constantinople was only a shadow of its former mighty self. Once it had been the capital city of the Eastern Roman Empire founded in 395. The extent of its dominions had reached across the North-African coast to Gibraltar, Italy, the Middle East, Asia Minor, and the Balkans.

But by the time of Mehmed’s conquest, the territory ruled by Constantinople only constituted a few islands in the Aegean.

The Eastern Roman Emperor Constantine XI Palaiologos recognized the imminent danger and asked the kingdoms of Europe for assistance. Only Genoa and Venice sent soldiers at the end of January — some 700 men, led by the young Genoese soldier Giovanni Giustiniani. A handful of Spaniards under Don Francisco de Toledo also arrived.

In the end, barely 7,000 men were ready to defend the city, while the Turks approached the gates with a host of about 150,000 soldiers backed by a gigantic fleet.

On April 1, 1453, the lookouts sighted the first Turkish banners on the horizon. Emperor Constantine then gave the order to close all the city gates. A massive iron chain blocked the entrance to the Golden Horn at Galata, and all the bridges leading into the city were destroyed.

The Sultan arrived with his main force on April 3. So began an eight-week long fight to the death. Yet, despite the formidable forces arrayed against him, Emperor Constantine XI ignored Mehmed’s demand for immediate surrender.

On April 6, 1453, the Ottoman guns started their bombardment that lasted day and night. Gradually, the Theodosian Walls began to crumble, chunk by chunk.

A contingent of Serbian miners was also among the attackers. Their job was to collapse the great walls through tunnel excavations and subterranean explosions. However, they had a superior opponent in the German engineer Johannes Grant. He succeeded in locating and destroying all the Turkish tunnel systems.

As a result, the destruction of the ramparts and the early conquest of the city was prevented.

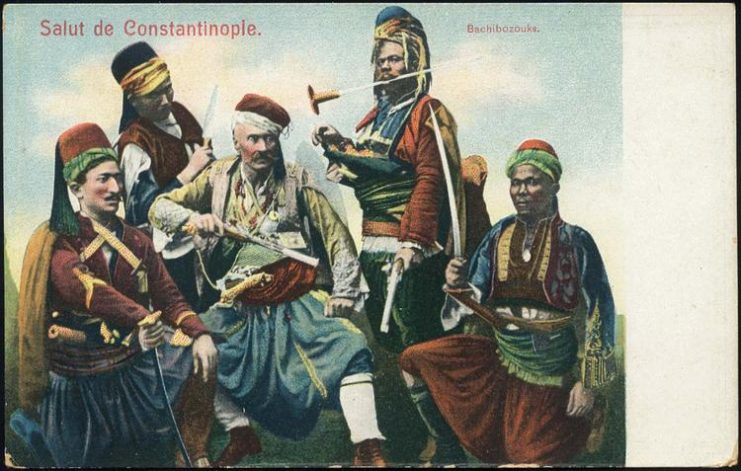

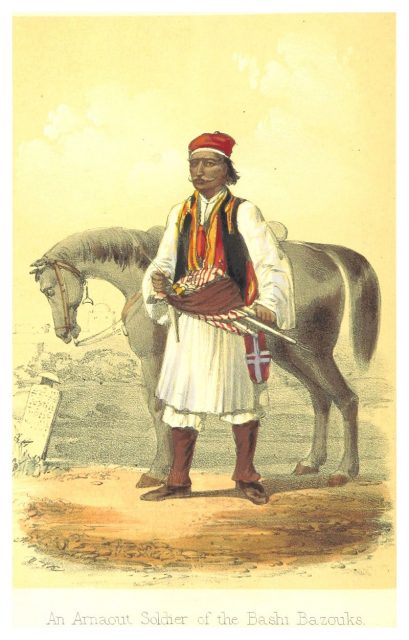

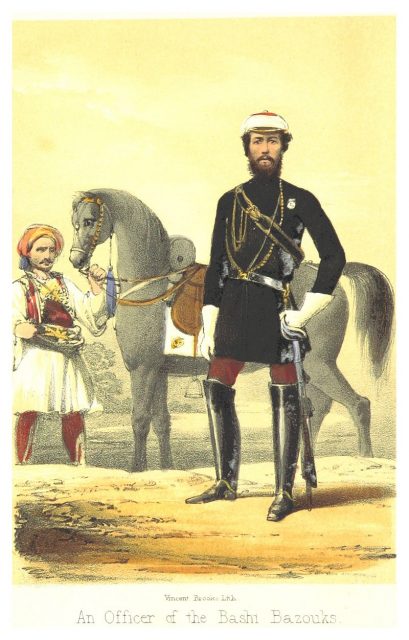

Whenever the siege guns managed to make a breach, Mehmed sent forth thousand upon thousand of “Bashi-Bazouks,” irregular mercenary units consisting of men from across the length and breadth of his empire.

These men carried a hodgepodge of weaponry such as scimitars, pikes, guns, and bows. They were unreliable troops at best, excellent in the first onslaught but easily discouraged if they did not immediately succeed.

When the Bashi-Bazouks, or cannon fodder, threatened to rout, several ranks of overseers equipped with whips or maces forcibly drove every panicked runaway back to the frontlines.

Only when the Bashi-Bazouks were wiped out did Mehmed order his Janissaries (elite troops recruited from the children of subjugated Christian families and converted to Isalm) to march forward.

The Ottomans stormed the city for three weeks. However, Giovanni Giustiniani’s expert defensive measures initially proved insurmountable. Sultan Mehmed needed to come up with something better or else he would be forced to forfeit the siege.

On April 22, Sultan Mehmed II gave the command that numerous oxen drag 70 war galleys on a road of greased logs from the Bosporus over the headland of Pera. The ships were then lowered into the water on the western side of the Golden Horn behind the iron chain blocking the entrance.

Now, Constantinople was threated from all directions.

The Sultan also thought that he had to do something for his men’s shattered morale. To stir up their desire to fight on, he proclaimed that the city would be theirs to plunder for three days. He promised them that anything including gold and silver, clothing and women would be theirs for the taking.

By a stroke of luck, the impregnable walls were breached

The besieged inhabitants knew that a concerted attack would take place the following day. Emperor Constantine XI attended a final religious service and gave a rousing speech to the men and women of Constantinople.

On the morning of May 29, two massive Turkish assaults were successfully repulsed. At this point, women and children had joined in the defense.

Then the Ottomans discovered a door ajar to the Kerkoporta Gate. After hoisting the Ottoman flag on one of the conquered towers, they flooded into the city like a river.

Constantine led the defenders from the front and pushed the enemy back. However, at this critical moment, a cannon splinter hit Giovanni Giustiniani. He sank to the ground bleeding. Upon seeing the demise of their wily erstwhile adversary, the Janissaries let out a howl of triumph.

Emperor Constantine fought to the last breath. He fell alongside his beloved city and was never seen again.

All hell broke out. Come midday, the streets and alleyways had turned red with blood. Houses were ransacked, women, men, and children were raped, brutalized or killed on the spot.

Many residents fled to the Hagia Sophia in search of salvation. But even there they were captured and forced into slavery or slain with the priests who were praying with them.

Out of a population of 50,000 souls, approximately 4,000 people were murdered. In addition, 30,000 ended up in slavery, the Ottomans now their masters.

In the eyes of the conquerors, the unbelievers had been made slaves, and the warriors of Islam had taken their beautiful girls into their tents for their pleasure.

Sultan Mehmed II entered Constantinople riding a white stallion a week after the sacking had begun. The streets ran with blood, and the buildings had been stripped of everything of value. All around him was desecrated and stripped bare.

The victorious and usually taciturn Sultan was almost moved to tears, apparently claiming, “What a city we have given over to plunder and destruction.”

He then proclaimed that no harm would be visited upon the survivors. Their property would be returned to them, their rank and religion safeguarded.

Read another story from us: Constantine: One Of Rome’s Greatest Emperors

When he stepped inside the Hagia Sophia, the Sultan gave the order to the chief imam that he should ascend the pulpit and proclaim a great victory in the name of Allah.

The newly named Istanbul soon became the capital city of the Ottoman Empire. A few generations later, under the reign of Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent, the Empire would reach its maximum expansion, rivaling even ancient Rome.