The 800-odd seamen who survived the sinking of the cruiser were greeted with a horrifying sight when the sun rose. Hundreds of shark fins cutting through the water.

The worst shark attack in recorded history also happened to be a disaster for the US Navy. When, on July 30, 1945, USS Indianapolis was sunk by a Japanese submarine, the Navy didn’t realize the ship had been lost until four days later – after which hundreds of men floating in the ocean for days had been eaten by sharks.

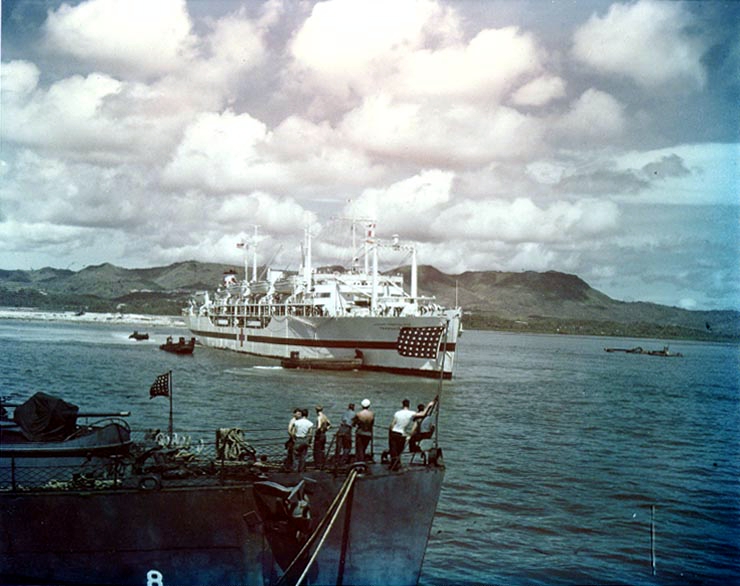

Toward the end of July 1945, the Portland-class heavy cruiser USS Indianapolis delivered a number of key components to be used for the construction of the atomic bomb that would be dropped on Hiroshima, to the Pacific island of Tinian.

Little did the crew of Indianapolis know of the horrors that lay in wait for them after they had completed this mission.

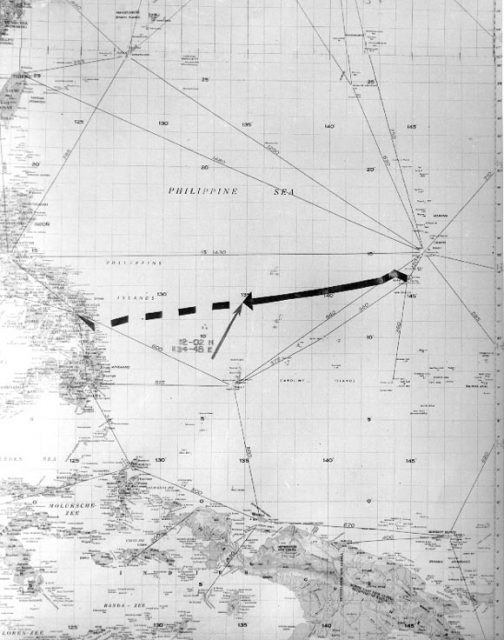

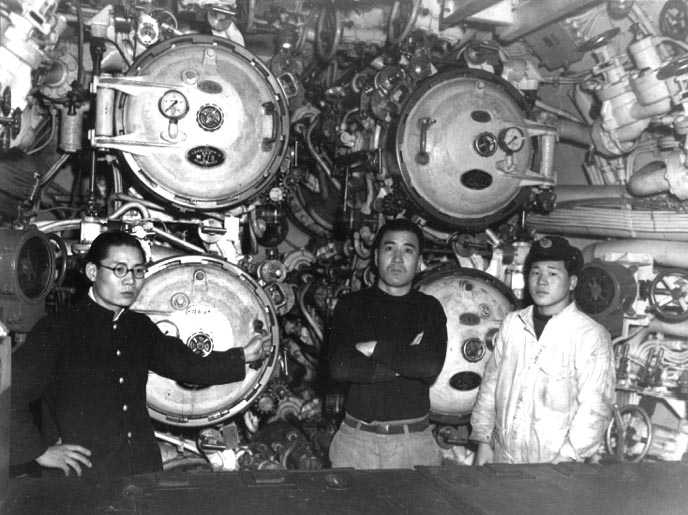

After delivering the components of the atomic bomb, USS Indianapolis set a course for the Philippines. However, just after midnight on the 30th of July, the cruiser was spotted by a Japanese I-class submarine. The Japanese didn’t hesitate to attack and successfully torpedoed the American ship.

Indianapolis was hit by two Japanese torpedoes, each of which did terrible damage. One hit a store of aviation fuel, and the other hit the ship’s own fuel tanks. The resulting explosions ripped the cruiser in half. The ship went down in 12 minutes, with around 300 seamen losing their lives as it sank.

USS Indianapolis had 1,196 sailors on board, and the 896 who survived the sinking must have thought that, despite the horrific nature of the disaster, a rescue effort would be close at hand. As it turned out, though, salvation would not come for four days – and those four days in the open sea would be four days of terror.

The danger of sharks to US servicemen – especially Navy personnel – in the Pacific has been known since the beginning of the war. Indeed, in July 1942, the Office of Strategic Services (the OSS, which was the predecessor to the CIA) started to investigate the possibility of developing a shark repellent to be used by Naval servicemen.

A number of different substances and combinations of substances were used in various OSS experiments. While initial progress was slow, a working formula was eventually found by combining copper acetate with black dye. It was proposed that pellets of this formula be attached to life jackets to keep sharks away from men in the water.

Unfortunately for the servicemen aboard USS Indianapolis, the Navy didn’t issue them with any of this shark repellent (which was later used up to the ‘70s, including on NASA equipment that came back from space and landed in the ocean).

The 800-odd seamen who survived the sinking of the cruiser and lived through the night were greeted with a horrifying sight when the sun rose the next morning: hundreds of shark fins cutting through the water.

The sharks had been attracted by the blood of all the sailors who had perished or been wounded from the explosions on Indianapolis, as well as by the thrashing of many bodies in the water.

A huge number of, most likely, oceanic whitetips (one of the most aggressive species of shark), began to swarm around the men who were bobbing in the water in lifejackets and life preservers.

There were plenty of bodies floating in the water for the sharks to feast on – but the feeding frenzy that ensued soon began to attract more and more sharks. And when the hundreds of sharks that had arrived finished with the floating bodies, they turned their attention to the living.

The sailors in the water quickly realized that their chances for survival would be maximized by banding together in groups. In this way, they could kick and punch approaching sharks together and keep an eye on each others’ backs.

Those men who were already injured, though, stood little chance against the ravenous animals. Anyone who was bleeding was attacked repeatedly until they succumbed. Individual men in the water made for easy targets for the sharks, who dispatched them swiftly.

Even for those lucky enough to have made it onto one of the few life rafts that had survived the sinking, things were difficult, to say the least. Almost no food or water had been salvaged from the cruiser because it had sunk so quickly. In addition, those on the life rafts were completely exposed to the sun.

Dehydration set in quickly, and within a day or two, some men were so tormented by their thirst that they started drinking seawater, which soon brought about an agonizing end. As the salt poisoning took effect, these men would often go mad and begin thrashing around in a frenzy – which not only attracted more sharks but also got them agitated and fired up to attack.

Sometimes, as these men drowned, they would grab onto other men in the water, and the force of their struggles would pull their comrades under the waves. In a desperate attempt to survive, some men would push the bodies of recently-deceased comrades toward the sharks in an attempt to draw the beasts’ attention away from themselves.

All in all, it is not certain how many seamen succumbed to shark attacks, how many drowned, and how many perished from ingesting seawater. What is known for certain is that the sharks who swarmed around the survivors for four days ate hundreds of the men. Estimates of the fatalities directly linked to the sharks range from dozens to over 150.

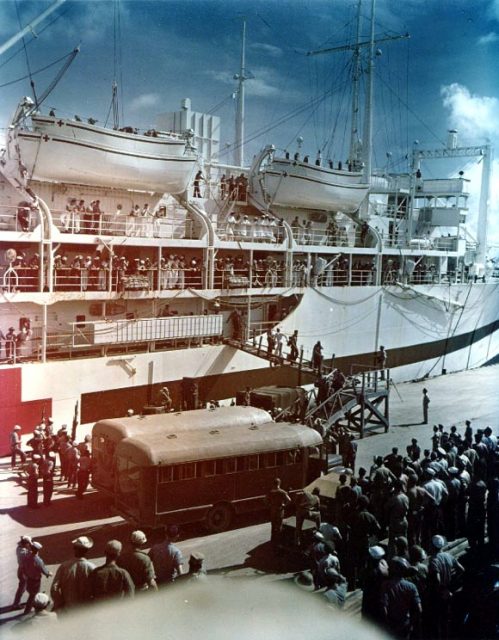

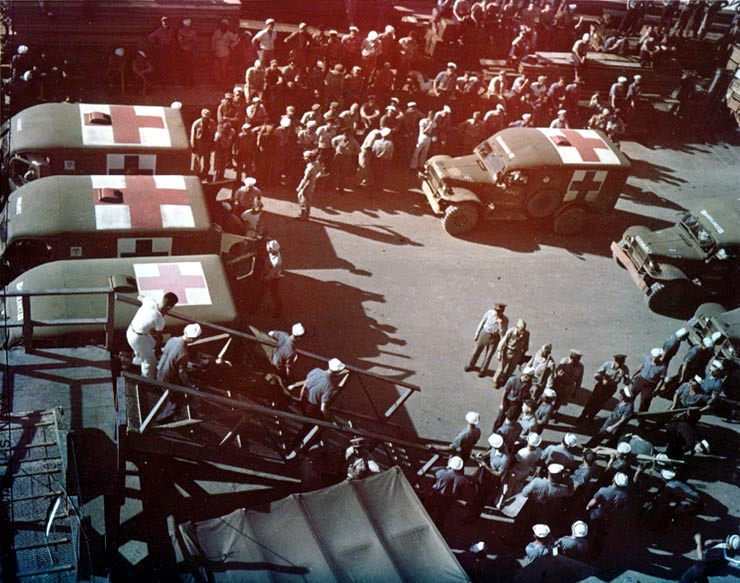

The remaining survivors were finally rescued four days after Indianapolis sank when a Navy aircraft flying over the ocean spotted the men floating in the ocean.

The Navy had actually intercepted a transmission from the Japanese submarine that had sunk the cruiser but had dismissed it as a ploy to lure American vessels into the area for an ambush.

Of the 1,196 servicemen who had been on the cruiser when it was torpedoed, only 317 lived to tell the tale. It was the greatest loss of life in a single incident in the history of the US Navy, and it remains to this day the worst shark attack in recorded history.

The US Navy blamed the captain of Indianapolis, Captain Charles McVay, for the disaster, stating that he failed to follow a zigzag course and thus made his ship vulnerable to attack.

Read another story from us: The Battle of the Atlantic

McVay was court-martialed in December 1945, but even though he was later restored to active duty, he was consumed by guilt and eventually took his own life.

McVay was officially exonerated from blame by President Clinton and Congress in 2000. For the captain of USS Indianapolis, though, the official exoneration came a few decades too late.