Wars don’t just happen on enormous battlefields–they are also conducted in secret meetings, back door deals, and one-on-one in conference rooms. Sometimes the talks that occur in these situations can alter the course of the war. That was the known case for at least one country.

In World War II, Italy was a nation that initially aligned itself with Hitler and the Nazis. By the summer of 1943, Italian officials knew they had made a huge error in doing so, and wanted to switch over to the Allied side instead.

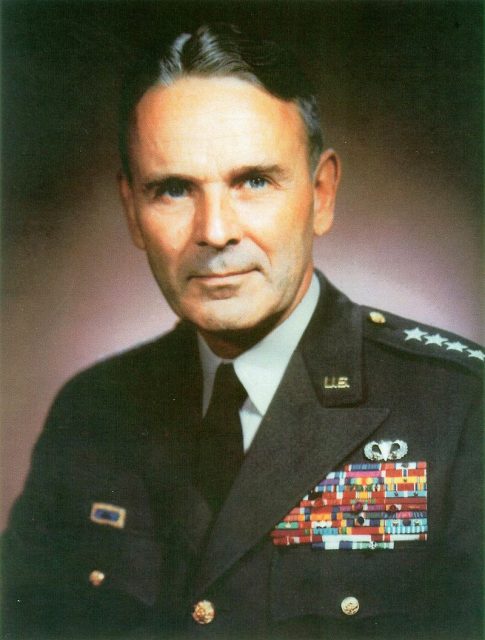

One man, General Maxwell (Max) Davenport Taylor, was instrumental in helping the Italians strike a bargain with the Allies. Mussolini had been ousted, and General Pietro Badoglio and Victor Emmanuel III were installed in Rome instead.

Taylor was asked by Dwight D. Eisenhower to help Italy get on the right side of the war. Eisenhower would later say of Taylor: “The risks he ran were greater than I asked any other agent or emissary to take during the war.”

It was July 1943 when Italian dictator Benito Mussolini was finally imprisoned. The new Italian leaders publicly kept siding with Germany, but meanwhile quietly negotiated to join the Allies, and a secret peace treaty was signed. Italy wanted to surrender, and in return, the Allies agreed to help prevent Rome’s takeover by the Nazis.

In what was coined Operation Giant II, British and American troops landed in key locations in Italy, including Sicily and Salerno.

The Allies disembarked quietly and slowly over the course of a few days, trying to avoid alerting the nearby German forces. However, once landed, they could not directly approach Rome by plane, for the risk of running into Nazi anti-aircraft fire was too great.

In order for the Allies to accomplish their proposed maneuvers successfully, Italy was asked to provide cover for the 82nd Airborne Division when it parachuted in close to five air strips near Rome. Italian officials quickly agreed – and that made General Taylor, and his colleague General Matthew Ridgway, exceptionally ill at ease.

Were the Italians promising something they could not deliver, out of fear of losing control of Rome to Germany?

The generals decided that Taylor and Colonel William Gardiner, an intelligence officer, would go to Rome to study the mission’s feasibility. They wanted a better idea of just what the Allies were getting into.

They left for Rome on September 7 in a British patrol boat. Once on land again, they climbed into a military ambulance and pretended to be prisoners caught at sea, complete with Italian “guards,” in case any Germans spotted them along the way. In that manner, they had to drive 75 nerve-racking miles to Rome.

Once safely ensconced in their quarters, they realized Italian officials were stalling. But why was Italian Chief of Staff Castellano dragging things out?

Any delays meant the Germans had time to reinforce troops near Rome, they insisted, and the prediction proved correct. German soldiers were, in fact, holding up Italian supply lines. Italian officials finally acknowledged that they could not ensure the safety of Allied troops at the airfields near Rome.

Taylor demanded to see the Prime Minister, whom they woke at about 2 a.m. Taylor and Gardiner soon realized that Bagdolio, too, was terrified of the Germans.

Like his generals, he was more afraid of Germany’s revenge for Italy’s armistice than he was anxious to help the Allies secure his country. He believed that if he and his men did not help the Allies, the Nazis would be less harsh when the Armistice was announced.

After relaying these developments to Eisenhower, Taylor was ordered back to North Africa. This return journey was pulled off without incident, but Taylor said afterwards that his flight back was incredibly stressful, as they could have been shot from the sky at any moment.

Read another story from us: Before Paris, There was Rome: the Forgotten Front

By the time the Armistice was announced on September 8, 1943, Germany had increased its presence near Rome enough to simply disarm Italian soldiers.

Those who did attack the Germans were murdered on the spot. The Italians paid a huge price for their indecision when the time came to change sides in a bloody, brutal war.