This true story details the actions of an aggressive warrior emperor from China’s less well known period of disunion. This was the largest time frame in which no single dynasty ruled China.

This was in roughly the same time period as the collapse of the Roman Empire in the 4th and 5th centuries AD. Much like in Europe, this period of disunion witnessed the introduction of a new religion (Buddhism). It also saw the synthesis of the barbarian invaders with the ethnic Han Chinese which created new leadership.

Emperor Wu started as a figurehead for what was the Northern Zhou Dynasty. In 572, roughly in the middle of the Merovingian dynasty in France, he deposed his cousin who was using him as a figurehead and started to rule in his own name.

In spite of (or perhaps because of) his time as a figurehead, he aggressively pursued a military solution to external threats.

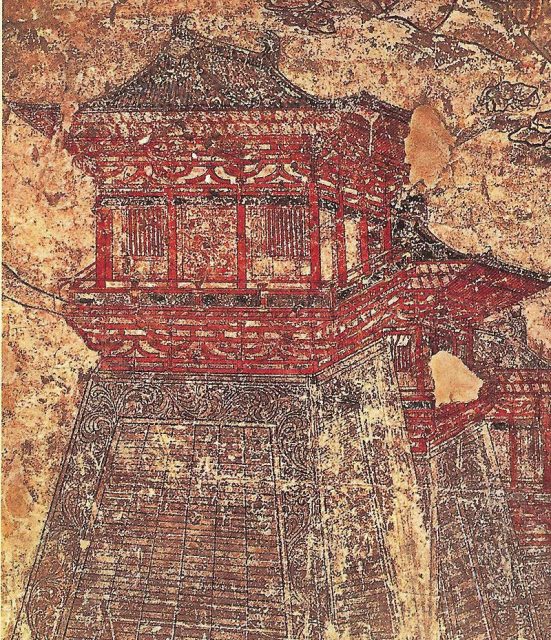

While the dynasty held powerful positions around the ancient capital of Chang’an (in the Wei River Valley just to the west of where it joined the Yellow River), their opponents held powerful positions to the east.

They held the citadel of Jiyong located in another former capital, Luoyang, which commanded the key passes. To the west of Jiyong fortress was the Tong Pass that led to the Northern Zhou heartland. To the east was Hulao pass and the administrative capital of the Northern Qi.

The latter pass was particularly important and has been called the Chinese Thermopylae since it was the site of strategic battles which led to the rise and fall of dynasties.

Battles between the two dynasties had ranged on and off for over 40 years before Emperor Wu assumed power. They both had strong defensive positions that made offensive actions rather difficult. In addition to a powerful fortress in the ruins of the former capital of Luoyang, the location of the city could be outflanked.

The North Qi based their military forces at Taiyuan. As the crow flies, it was directly north of Luoyang, but it was in the Fen River valley which ran southwest until it joined the Yellow River.

An army that moved a short distance to the south of that junction would find themselves directly behind any army trying to seize Jiyong fortress. Thus it didn’t take that much effort for the Northern Qi to threaten Emperor Wu’s supply lines.

This is exactly what happened in Wu’s first campaign. The Zhou army besieged the fortress, the emperor got ill, and the Northern Qi army marched southwest from Taiyuan to end the campaign after a mere 18 days.

It was at this point that the Emperor came up with a new strategy that would “grasp the throat” of his enemy by marching directly towards the enemy army to his northeast. His generals thought this was too risky, that it might even be impossible to march directly into the power of their main rival, but he overruled them.

He started his campaign on November 10, 576, by attacking the fortress of Pingyang, near where the course of the Fen River turns west to flow into the Yellow River. The town fell in early December due to the treachery of a commander on the inside.

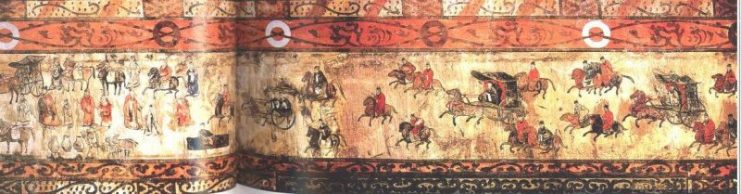

When the relief army arrived, Wu left 10,000 men in the newly conquered fortress and retreated to a nearby friendly fortress. Two months into the war on January 10, 577, the two armies finally met. Gao Wei, the enemy commander and rival emperor opposite Emperor Wu, had dug a ditch that prevented Emperor Wu from charging his enemy like he wanted.

It was midday when the emperor was convinced by his eunuch advisers that it was unbecoming to hide behind trenches. He ordered them filled and battle was joined. It was a close run affair until Gao Wei retreated and Emperor Wu captured 10,000 and broke the siege.

His generals again suggested that he hold back, but he disagreed: “Let go of the enemy and troubles will arise. If you gentlemen have doubts, I will go after them alone.”

He reached the military garrison at Taiyuan a week later on January 17th. He drove back an army of 40,000 that fought him outside of the city, then he led a small force of elite heavy cavalry (the decisive component of armed forces in this period) through the east gate to create a foothold within the city walls.

Gao realized how dangerous this was and sent a furious counterattack charging Wu’s position. They hacked through the foothold and would have captured or killed the emperor himself except there were so many bodies that the Qi soldiers couldn’t close the gate of the city.

Emperor Wu regathered his forces (and presumably his composure) and attacked the next day. The city fell, he moved through the Fokou Pass unopposed and mopped up the opposition around the administrative capital at Ye that had hindered his relatives for the last generation.

The lessons of this encounter are numerous. Wu attacked the center of his opponent’s strength and showed his capability on the field and in siege warfare.

He led many attacks, including an astounding fight inside the walls of a hostile city and escaped because dead soldiers jammed the door.

He should be remembered as an individual who showed boldness in strategy and active battle. Leadership can overcome geographic constraints, and warfare was a vital part of the creation and dissolution of Chinese polities.