On November 3, 1914, before the United Kingdom even officially declared war on the Ottomans, Churchill ordered bombardments to begin.

The European Great Powers had little respect for the Ottoman Empire by 1914. Italy had taken the stage as a Great Power by defeating the Ottomans only several years previously, taking their North African land in the process. Many Europeans believed that the “Sick Man of Europe” had been replaced as a Great Power by Italy.

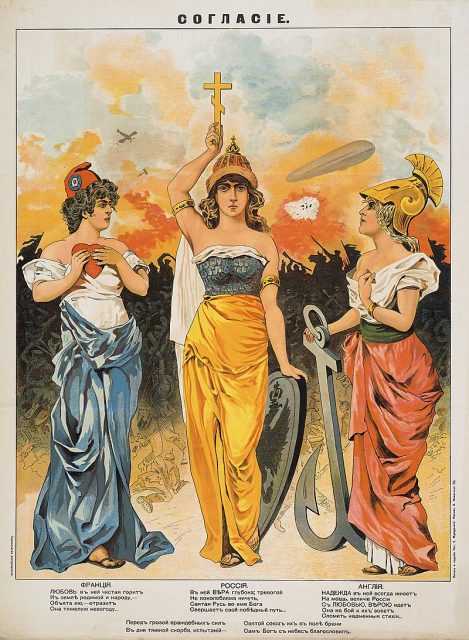

However, the Central Powers of Germany, Austria-Hungary, and Italy (Italy abandoned the alliance when the war began), realized they needed an ally in the East. The Entente Powers included Russia, France, and the United Kingdom, ensuring a two-front war against Germany if a war broke out between the two alliances.

Germany realized that the Ottomans could open a second front against Russia in the Caucasus, pulling troops away from the Eastern Front. Although the Entente looked down upon the Ottomans, they would soon learn the danger of hubris.

A Bold and Overconfident Attack

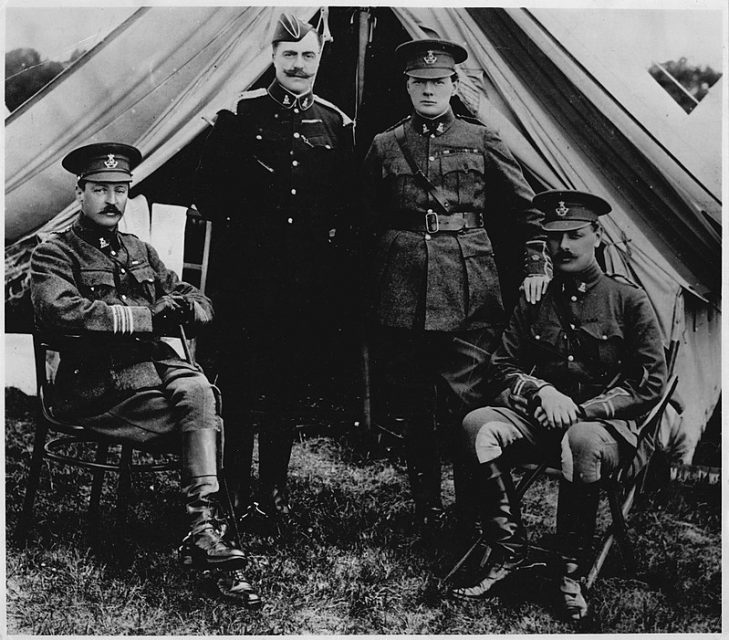

By late 1914 the Western Front of the Great War was at a standstill. Despite being in a two-front war, the Germans and Austro-Hungarians held firm in the face of Allied counter-attacks. However, some Entente leaders, including an up and coming politician named Winston Churchill, felt that they had an opportunity to open another front in the war.

As the First Lord of the Admiralty, Churchill had significant influence over military decision making, and was looking for a great victory. He realized that the Ottomans were the weakest link in the Central Powers, and felt that the Allied navy could defeat them quickly.

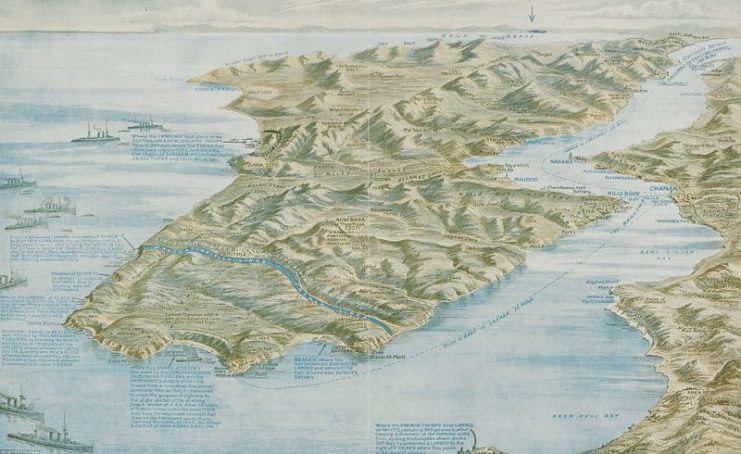

The plan was simple: naval access to the Ottoman capital, Istanbul, was guarded by a key strait called the Dardanelles. The Allies believed that if they could force the strait, they could take the capital.

Since many Ottoman troops were busy fighting Russia in the Caucasus, the Allies expected only light resistance. In theory, they would knock the Ottomans out of the war quickly, with few casualties, and then neutral Balkan countries might join the Allies, opening a new front.

In addition, the Russians were putting pressure on their western Allies to launch such an assault to pull Ottoman troops away from the Caucasus, open supply lines through the Black Sea, and allow the Russians to send their troops to fight Germany. This assault could change the entire course of the war.

On November 3, 1914, before the United Kingdom even officially declared war on the Ottomans, Churchill ordered bombardments to begin.

Everything about the bombardment seemed to confirm Allied suspicions that the Ottomans were weak. The 20 minute bombardment destroyed a magazine, along with at least ten guns, and inflicted 150 casualties. However, growing Allied overconfidence would soon come back to bite them.

Surprising Resistance

The French and British forces prepared for a full assault over the next few months. The Allies learned that the Ottoman guns were mostly outdated, which allowed the Allies could stay out of their range while bombarding the coast. However, the Ottomans took advantage of this time to prepare stronger defenses throughout the straits.

Naval bombardments began again on February 19, 1915. Although the Allied navy found that they could pass through the defenses at the beginning of the strait, they soon ran into trouble.

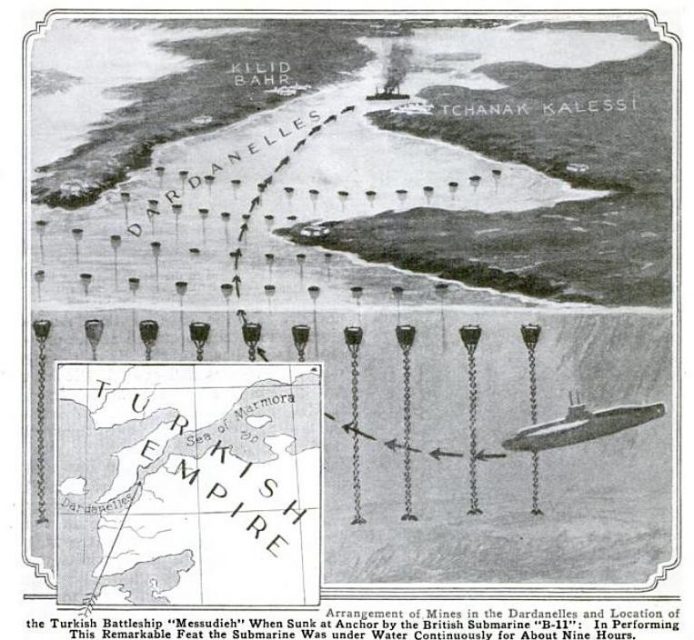

Defenses further into the straits were better fortified, and naval bombardments had little impact on them. The British discovered that only direct hits could destroy the guns in this area, and feared that they would run out of ammunition if they kept up a long bombardment. They also discovered hundreds of naval mines they would have to clear.

Unfortunately for the Allies, their minesweeping ships were unarmed and manned by civilians. These civilians generally refused to work under bombardment, and the ships were easily damaged by coastal batteries.

The Ottoman Empire Strikes Back

The Allies realized they needed a new strategy, and planned for a large offensive on March 18, 1915. However, the Ottomans were aware that an attack was coming, and came up with a unique plan to stop it.

The Ottomans had noticed that the Allied ships would always turn to their starboard side when withdrawing after bombardments. It was with this information that a single Ottoman ship turned the tide of the entire battle.

On the night of March 17-18 the Nusret laid mines parallel to the coast, rather than across the strait like the other minefields. At around 11 AM on the 18th, the Allies began their attack. Three of their ships were badly damaged early on by fire from the shore.

However, they had successfully damaged and partially silenced the shore batteries over the course of a few hours. Rear Admiral John de Robeck, the commander of the operation, ordered his first battle line to fall back, and for his second to advance.

The French battleship Bouvet made the usual starboard turn to withdraw and suddenly struck one of the newly laid mines. It sank in only a few minutes, taking over 600 men with it. For the next two hours the Allies did not know what had hit Bouvet, since the area had previously been cleared of mines.

Then HMS Inflexible hit another mine during its withdrawal from the battle. Inflexible ran aground, but was able to be repaired.

The Allied fleet was clearly in trouble when a third ship, HMS Irresistible, struck a mine and started sinking. Admiral de Robeck sent HMS Ocean to try to tow Irresistible to safety, but Ocean itself promptly hit a mine and also began sinking. The Allies retreated as the sun set.

Aftermath and Gallipoli

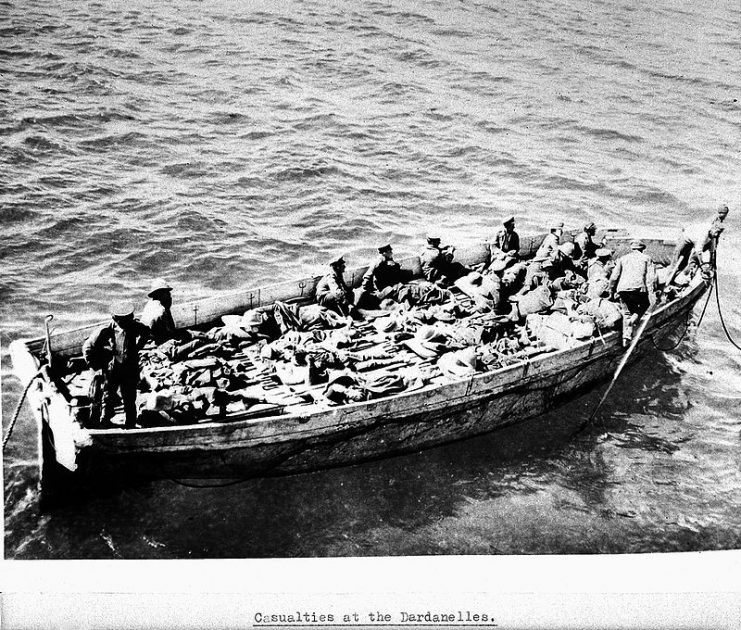

The Allied fleet suffered three ships sunk, and three more badly damaged. Around a third of the entire fleet in the Dardanelles was now out of commission. Over 700 Allied sailors were dead, with many more wounded, while the Ottomans only suffered around 120 total casualties.

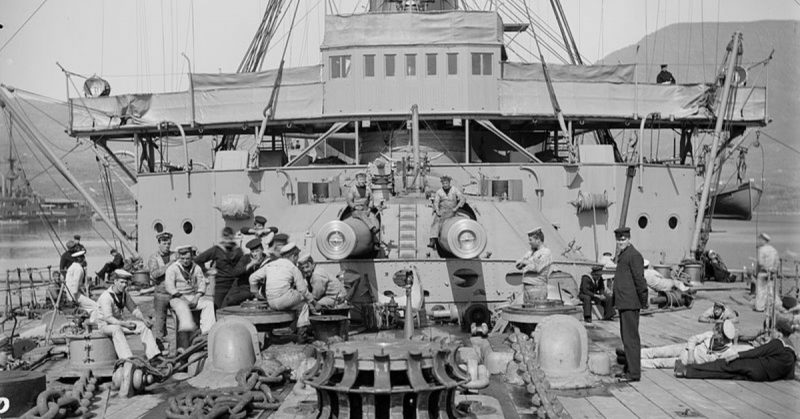

There was only one bright spot for the Allies during the Dardanelles campaign: the success of their submarines. Allied submarines sank a number of Ottoman ships, including the Mesûdiye, disrupted shipping, landed demolition crews to destroy emplacements on the shore, and destroyed a railway bridge.

By the end of the campaign the submarines had destroyed one battleship, one destroyer, five gunboats, 11 transport vessels, 44 supply ships, and around 150 smaller ships, while suffering eight submarines lost. However, these successes did not prevent the campaign’s overall failure.

Read another story from us: A Consequence of Arrogance? – The Battle of Gallipoli

After the disaster on March 18 the Allies debated how to continue the campaign. Churchill was convinced that the losses could be replaced and believed (incorrectly) that the Ottomans were running out of ammunition, so he wanted to launch another naval attack.

De Robeck feared that Istanbul might not surrender from bombardment alone, and decided that any future attacks required a landing force. On April 25, 1915, Allied forces landed on the beaches of Gallipoli, but that debacle requires its own article.