As the guns went silent on May 8, 1945, after Germany had capitulated, a wave of mistrust was crashing the shores of Allied-Soviet relations. Due to the rapid advance of the Red Army during the last year of the war, the question of the division of Europe was becoming the hot topic.

Burning hot, you might say, as Churchill was already sketching up a plan to turn the tide in Europe and “to impose upon Russia the will of the United States and the British Empire.” This sentence was contained in an official secret document issued on May 22, 1945, entitled quite suitably – Operation Unthinkable. The objective included another paragraph which further explained the background of Allied intentions:

“Even though ‘the will’ of these two countries may be defined as no more than a square deal for Poland, that does not necessarily limit the military commitment.”

“A square deal for Poland” is a reference to the decision made during the Yalta Conference held in February 1945, when it was concluded that the far eastern part of Poland known as the region of Kresy, was to remain within the borders of a re-established Polish Republic.

Many of the Polish soldiers who were fighting alongside the British during the war originated from that region, and the decision was taken to reward them for their war efforts. When Stalin annexed the eastern outskirts of Poland, Churchill was furious.

Of course, this situation was the motive, but not the real reason for coming up with Operation Unthinkable. Soviet military presence in Europe was concerning the British Prime Minister. So was the fact that the Soviet Union was gaining a reputation as being the most important factor in Hitler’s demise.

He firmly believed that Britain should initiate the fight against the threat from the East. However, his military staff were not delighted to hear that another war was on the horizon so soon after the bells of peace had chimed.

After learning of the plan, Alan Brooke, Britain’s Chief of Army Staff, wrote in his diary:

“Winston (Churchill) gives me the feeling of already longing for another war.”

Nevertheless, military experts were working on all possible scenarios for such a conflict. The intention was to create a frontline between Hamburg to the north and Trieste in the south.

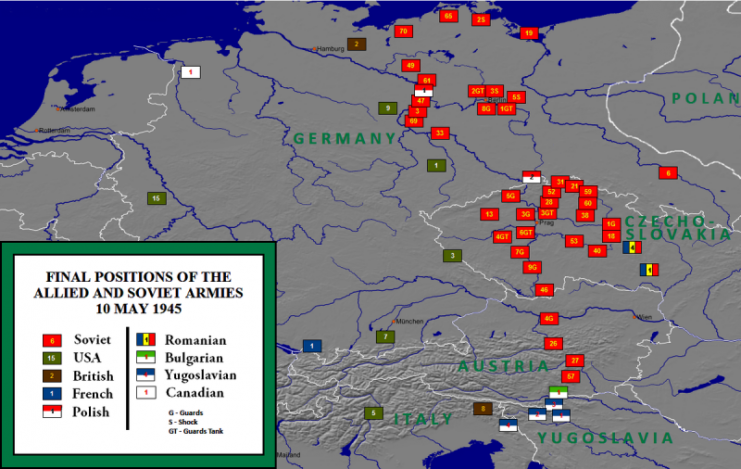

The Allies in Europe were operating with 64 American divisions, 35 British and Dominion divisions and 4 Polish divisions. They also included 10 German Wehrmacht divisions, which was considered far-fetched. Not only that in 1945, nobody knew the real state of the Wehrmacht, but the morale of those troops was at a bare minimum.

If anyone wanted to avoid a continuation of conflict at the time, it was Germany. The real assessment was around 103 divisions in total, including 23 armored ones.

Opposed to them was the Red Army with 264 divisions positioned all over Eastern Europe and Germany. They also had 36 armored divisions at their disposal.

Of course, another important factor in the potential war between the superpowers was their air power.

The Allied Tactical Air Forces in North West Europe and the Mediterranean could muster an admirable air fleet consisting of 6,714 fighter planes and 2,464 bombers, but the numbers were not on their side. Regarding quantity, the USSR once again held the advantage with 9,380 fighter aircraft and 3,380 bombers.

What perhaps motivated Winston Churchill the most was the newly invented and freshly tested atomic bomb, possessed by his life-long ally, the United States.

Allegedly, Churchill, hyped by the success of the use of the weapon on the Japanese, told Brooke during the Potsdam Conference in July 1945:

“We can tell the Russians if they insist on doing this or that, well we can just blot out Moscow, then Stalingrad, then Kiev, then Sevastopol.”

After studies conducted by British Army Staff, it was concluded that, if they were to proceed, the same fate would await the Allies as the one that met Napoleon, and more recently Hitler. Russia was too vast to conquer. In addition, the army behind the red banner was by 1945 a powerful military force staffed with veteran soldiers and officers, equipped with advanced technology and – above all – commanded by a strong and determined leader.

To gain the advantage, i.e., the Atom Bomb, Churchill needed the support of his American counterpart. But President Harry Truman showed no interest in the plan whatsoever. He was not going to spark a new conflict, just after the biggest war in the history of humanity was finally over. Truman addressed Churchill via cable, advising that the USA had no intention of participating in, let alone leading, Operation Unthinkable.

As the Americans were re-directing their forces from Europe to the Pacific Theatre and back to the US in June 1945, the fear of a Soviet advance towards the North Sea and the Atlantic started to haunt the cigar-smoking British Prime Minister.

He turned his plan of offense to defense. Relations between the USSR and Great Britain were deteriorating as rumors of a potential conflict reached the Kremlin. Churchill’s fears grew stronger:

“It is possible the Russian Air Force would attempt to attack all types of important targets in the UK with its existing aircraft. The Russians are likely to make full use of new weapons, such as the rocket and pilotless aircraft….We must expect a far heavier scale of attack than the Germans were able to develop (such as the V-2 rocket).”

Luckily, a diplomatic stalemate was reached. Nevertheless, the first years of the Cold War were still substantially hot, as sparks flew between the Allied-occupied and Soviet-occupied areas of Europe.

In 1946, a land dispute arose between Yugoslavia and Italy concerning the region of the Julian marshes. In those times, a petty quarrel could potentially lead to a full-blown war between the East and the West in Europe, and a territorial dispute was no petty quarrel. Once again, luckily, an agreement was struck between the countries.

The events surrounding the fallout of the Soviet-Allied wartime coalition, including Operation Unthinkable, are today often considered to be at the very core of the Cold War. Although such incidents were usually resolved peacefully, the mutual mistrust between the superpowers led to several proxy-wars which shaped the geopolitical picture of the world in which we live today.

The shadow of Churchill’s plan was in one way or another present throughout the 20th century, as the world watched potential escalations between the USA and the USSR. The threat of a total nuclear war and the consequences of such a conflict eventually tipped the weight of the power struggle. The various leaders comprehended that it was a one-way ticket to complete annihilation of the world as we know it.

Operation Unthinkable remained just that – unthinkable.