War History Online presents this Guest Article from Ned Forney

We’ll never know the terror 18-year-old Marine PFC Edward “Eddie” Thorn experienced in the final minutes of his life, but we do know that what he and hundreds of other Marines went through at the Chosin, or “Changjin,” Reservoir was unimaginable.

Shivering on a wind-swept, snow-covered hill on the night of November 28, 1950, PFC Thorn would almost certainly have been staring wide-eyed into the cold, black night, his weapon loaded, nerves taut, and mind racing. At approximately midnight, the Chinese attacked. An overwhelming sense of fear, apprehension, and dread – mixed with feelings of determination, camaraderie, and pride – must have swarmed over him as the battle began.

The Fight For “Hill 1282”

With bugles blaring, machine gun and mortar fire erupting, and hundreds of Chinese rushing towards him, PFC Thorn did what every Marine did that night. He fought viciously. In the ensuing carnage and death, incredible acts of valor and sacrifice occurred. When daylight broke, countless dead American Marines and Chinese soldiers lay exposed in the subzero cold, their frozen arms and legs twisted in macabre testaments to their last moments of life.

Miraculously, Thorn had survived. Out of the 176 Marines in his unit (Easy Company, 2nd Battalion, 7th Marine Regiment), 120 were dead or wounded. The fight for Hill 1282 would be remembered as one the fiercest in Marine Corps history.

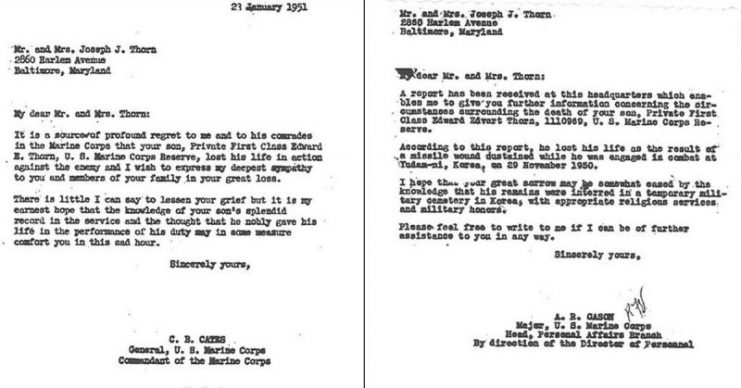

But the fighting wasn’t over. In a second attack, PFC Thorn, three weeks shy of his 19th birthday, was killed by an enemy bullet. He was buried at 1st Marine Cemetery in Yudam-Ni, near Chosin, on December 1. Eddie’s parents received a letter two months later from Marine Corps Commandant General Clifton B. Cates:

It is a source of profound regret to me and his comrades in the Marine Corps that your son, Private First Class Edward E. Thorn, US Marine Corps Reserve, lost his life in action against the enemy and I wish to express my deepest sympathy to you and members of your family in your great loss.

There is little I can say to lessen your grief but it is my earnest hope that the knowledge of your son’s splendid record in the service and the thought that he nobly gave his life in the performance of his duty may in some measure comfort you in this sad hour.

Joining The Marines

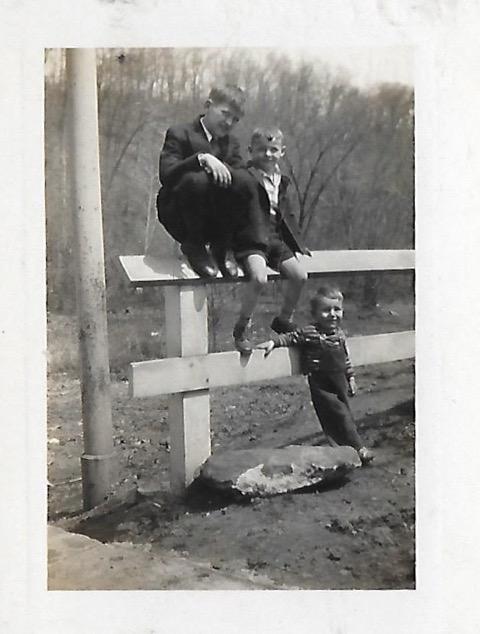

Born on December 28, 1931, Eddie Thorn, the twelfth child of Joseph and Whilimena Thorn (remarkably, they had fourteen children) grew up in Dickeyville, an historic district in Baltimore, Maryland. As a kid, he loved the outdoors and playing with his three best friends from across the street: Tommy, Dickie, and Steve Moran. The four boys did everything together and as teenagers were inseparable. When they weren’t playing sports, listening to music, going to dances (Eddie was apparently quite the dancer) or working part-time jobs, they were looking for girlfriends.

In October of 1949, young, handsome, and eager to impress the young ladies, they enlisted in the US Marines. They wanted to serve their country and be part of organization revered by their family and friends. After graduating from boot camp, they returned home and were assigned to a reserve unit.

With World War II over and the chance of another conflict breaking out unlikely, it didn’t look like they would be deploying any time soon. And then the Korean War started.

By September 1950, the four Marines were at Camp Pendleton preparing to mobilize. On October 15, the young men who had spent their entire childhood and adolescent years together suddenly found themselves separated. Eddie was shipping out for Korea, and the Moran brothers would be remaining Stateside.

PFC Thorn arrived in Wonsan, North Korea, on November 11 and quickly joined his unit. Two days after eating a Thanksgiving dinner in the field and hearing rumors of everyone going home by Christmas, the Chinese attacked in force. “We face an entirely new war,” Gen. Douglas MacArthur cabled to Washington on November 28. A day later, Thorn was killed.

“My God He Was So Young”

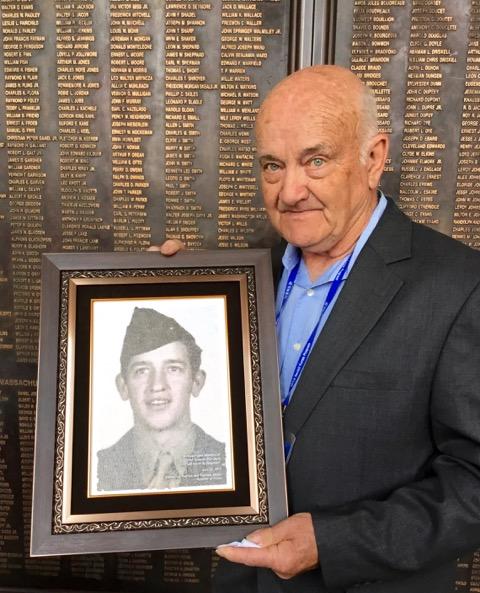

Bob Thorn, one of Eddie Thorn’s nephews, was only five when his Uncle Eddie died. “I heard stories about him when I was growing up: how he joined the Marines, served in Korea and was killed. But that was all I knew,” Bob recalled. “When I finally found a photo of him in his Marine uniform, all I could think of was, ‘My God he was so young.’”

Today Bob is leading a fight that would make his uncle proud. In 2000, inspired by Ted and Hal Barker, the founders of the Korean War Project, Bob began looking into how his uncle and thousands of other US servicemen might be returned to US soil. “It was time for them to come home,” Bob explained when we met in April during his visit to South Korea with the Ministry of Patriots and Veterans Affairs “Fallen Heroes of the Korean War” program.

After nearly 20 years of dedication and perseverance, Bob now serves as an advocate for all families with a loved one listed as MIA (Missing In Action), KIA (Killed In Action) and POW (Prisoner Of War). Through countless meetings, phone calls, and written correspondence with military and Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency officials and at least a handful of trips to Washington, DC, and Hawaii, he’s learned that his uncle’s remains, along with the remains of more than 4,000 others who died during the Korean War, were disinterred, sent to Hawaii, and re-buried at the National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific, also known as the “Punchbowl.”

With advances in DNA testing and Bob’s relentless pursuit of the truth, he’s on the cusp of finding his uncle’s remains. He’s narrowed down PFC Thorn’s gravesite down to 13 plots at the Punchbowl, and the DPAA has agreed to exhume the remains at each site.

In April of 2017, the first body was exhumed, identified, returned to the family, and given a proper military burial. The deceased wasn’t PFC Thorn but Bob is proud of the part he played in the process. “One down, twelve to go,” he told me with his usual determined look.

“Hopefully I’ll still be here when Eddie is identified,” he added. “It’s taken me 26 years to get this far, and hopefully it won’t be much longer.”

Thank you, Mr. Thorn, for your hard work and loyalty to your uncle and to all those who served in the Korean War.

Ned Forney Website