Norman knights continued their pillaging of Italian and papal lands.

Through victory, conquest, determination, and opportunity, the Normans traveled far to be leaders and kings of foreign lands and peoples. Unrelenting in their resolve and vicious in their methodology, they were seemingly unstoppable as they carved their way to glory and dominion.

Fueled by a competent and consistent brutality reflective of a people dedicated wholeheartedly to war, by 1081 CE they had reached the Balkan city of Dyrrhachium. Ambitious and unforgiving as ever, they were prepared to destroy the last remnants of an ancient empire.

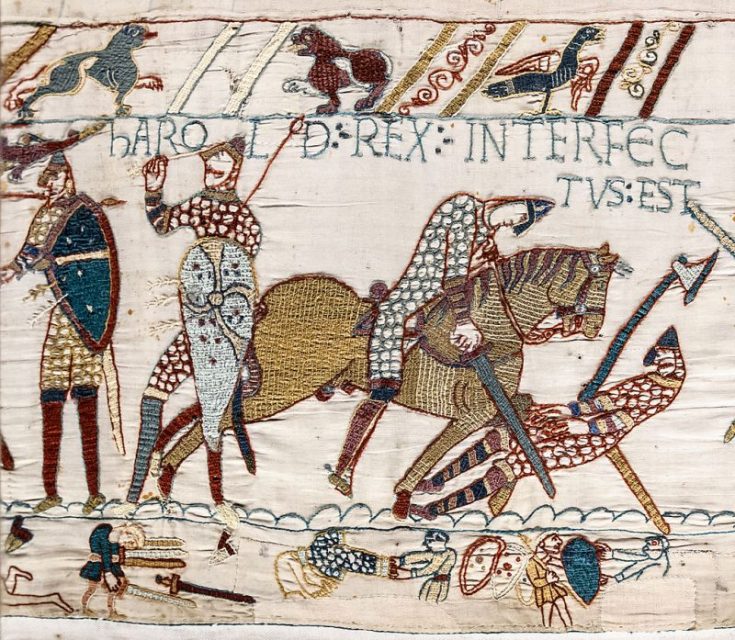

Though best known for their conquest of England in 1066 CE, the Norman’s history and spirit have always meant that they set their sights abroad. King Charles III of West Francia had established the Duchy of Normandy for the Norse leader Rollo in 911 CE, hoping to satiate the Viking warriors pouring into his realm.

Accepting the bargain, these “Northmans” began a rapid change of culture and administration, adopting the lifestyles of Carolingian feudalism and Christianity. But while their affinity for assimilation produced an efficient and effective state, their attitude and approach to the world changed little.

They had won land and formed a domain of their own, but they were far from being satisfied with what they had accomplished. As their devotion to Christianity grew, their interest in Rome and the church began to involve them with the Mediterranean world.

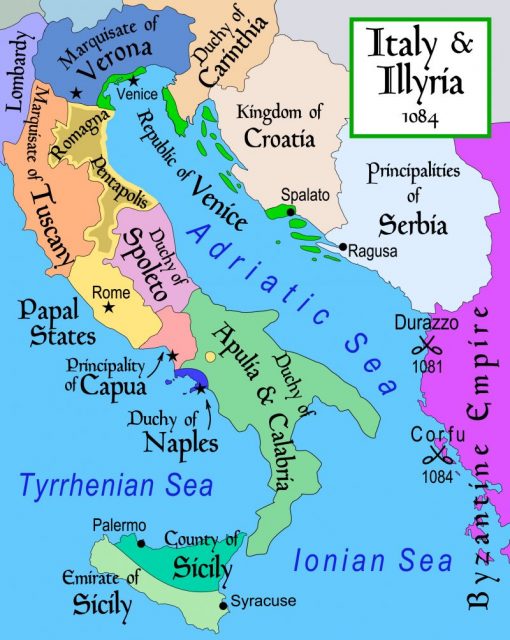

The Muslim Aghlabids, the Byzantine Empire, and the Germanic kingdoms of the West were locked in a violent struggle for Southern Italy and Sicily. As they fought over the ruins of the Western Roman Empire, each believed themselves to be the rightful rulers of a new world.

For one Norman family, the Hautevilles, the battleground in Southern Europe presented dreams of incredible enterprise. William and Drogo de Hauteville were the first to arrive in Italy in 1038 CE, and they quickly began making themselves a lucrative living as professional mercenaries.

When they were hired by the Byzantine Empire to fight against the Aghlabids in Sicily, the knights proved their worth by achieving stunning victories steeped in heroic deeds.

But when the Normans became determined to keep the lands that they had won, they rebelled against their Eastern Roman employers. Choosing to form new nations of their own, they refused to give away what they had earned.

Now considering themselves members of the pious Western kingdoms, the Normans knew their entitlement would need official recognition from traditional powers.

To solidify their conquests, they turned to the Lombard Prince of Salerno, Guaimar IV, who allowed William and Drogo to establish a fiefdom in Apulia, a land the Normans had conquered during their adventures in Southern Italy. For better or for worse, the invitation meant that the knights would be staying indefinitely, and by 1042 CE William was proclaimed Count of Apulia.

Guaimar and William continued towards Calabria, conquering the province in 1044 CE. After gaining the support of the Holy Roman Emperor, Henry III, the County of Aversa and the County of Apulia were officially conferred to the Normans. This began the foundations of a state that would become a powerful and world-shaping nation.

After William’s death in 1046 CE, Drogo was elected by the Normans to be his successor. He began by paying homage to the Holy Roman Empire, solidifying the foundations of his rule, and being declared “Duke and Master of all Italy and Count of all the Normans of Apulia and Calabria” by the Emperor.

But the military presence of the Normans was not as well received by the local powers and peoples of Italy. Mercenary work still proved to be the most effective path to survival, and it was soldiering Norman warlords that continued to find their way to southern Europe.

In an effort to earn Pope Leo IX’s trust, Drogo agreed to quell the growing chaos being caused by Norman sell-swords, but as he returned from his meeting with the religious leader, he was assassinated by anti-Norman conspirators.

When his brother, Humphrey, took the reins of leadership, he quickly began a quest for revenge as outraged Norman knights continued their pillaging of Italian and papal lands.

When Robert, one of the younger brothers of the Hauteville family, arrived to carve his own domain, he began by earning a modest living as a leader of raiders and marauders. Having been given the castle of Scribla in Calabria by his brother Drogo before his death, he found the sparse resources of his land difficult to manage.

Within these harsh conditions, however, he became a proficient warlord, ravaging the remaining towns still loyal to the Byzantine Empire in Southern Italy. During his ventures, Robert gained a reputation for his boldness and intellect in battle, earning himself the nickname “Guiscard,” meaning “crafty.”

But Pope Leo IX and the Holy Roman Emperor had finally had enough of the Norman presence and the problems it was beginning to cause. After gathering an army of Italian soldiers and Swabian mercenaries, the Pope marched south to end their incursions.

The following Battle of Civitate in 1053 CE was a disaster for the papacy. After having his army crushed by the Normans, Pope Leo IX was captured and brought to Benevento. With their assertion of authority in the West validated by war, the Normans continued to consolidate and expand their realm until Humphrey’s death in 1057 CE.

Robert was declared his successor until Humphrey’s son, Abelard, came of age to rule. But the opportunity to gain power overcame Robert. After seizing Abelards’s holdings, he declared himself the new leader of the Normans.

As the papacy changed hands with Pope Leo IX’s death in 1054 CE, so did their attitudes towards the Normans. Faced with the schism between the Greek and Latin churches, the new Pope Nicholas II saw their victorious neighbors as an asset to control Eastern Roman expansionism.

In 1059 CE, the Norman conquests were again validated by the Western Roman church, declaring Robert the Duke of Apulia, Calabria, and Sicily. In return, Robert recognized papal authority and agreed to serve its interests at home and abroad. Robert set to work establishing his power and control over the lands for which he now held legitimate titles.

After brutal campaigns in southern Italy and Sicily with his younger brother Roger, Robert began to look across the Adriatic Sea. Having removed the last vestiges of Byzantine forces from his lands, an invasion of the Eastern Roman Empire now seemed an achievable reality.

Though rebellions persisted among the disgruntled populations of the conquered, Robert’s diligent repression within his regions earned him further recognition as a ruler. Renewing his vows to the papacy in 1080 CE to Pope Gregory VII, he now began to concoct a plan to dismantle Byzantine power for good.

By 1081 CE, he was prepared to attack them directly, and his ambitions lay at the seat of imperial power: Constantinople.

In May, he set sail from Brindisi and Bari with a fleet of 300 ships, carrying some 25,000 to 30,000 soldiers and knights. When he arrived at the city of Dyyrhachium (also known as Durrazo) in modern-day Albania, he settled in for a siege.

But Robert’s military excursion quickly began to turn against him. The Byzantines appealed to the Venetians for aid who, with their superior ships and naval tactics, destroyed the Norman fleet. Dyyrhachium’s garrison proved to be resilient, withstanding vicious assaults from powerful siege engines. Disease broke out amongst the Norman camp and decimated their numbers.

Despite their losses amid the growing signs of defeat and failure, however, Robert and his men refused to relent.

Alexius I, the newly crowned Eastern Roman Emperor, came to realize the extent of the Normans’ resolve and determination. He set forth to relieve his beleaguered troops at Dyyrhachium with around 25,000 men, a hastily formed army that consisted mostly of levies and mercenaries.

In a bitter twist of irony, the soldiers of his elite Varangian Guard, an impressive collection of Anglo-Saxon and Viking mercenaries, were warriors that had fled England after William the Conqueror’s victory at Hastings. Once again they faced their Norman enemies, and they were more than eager for revenge.

These skilled and experienced soldiers would be relied upon to turn the tide of battle for Alexius. When the armies finally met in October of the same year, he placed them in the center to hold against the inevitable charge of the Norman knights.

The Normans began the battle by attempting to draw Alexius’s army forward, feigning a cavalry charge down the center. But when they were forced back by the disciplined missile fire of the Eastern Roman archers, the Normans began a direct assault on the Emperor’s left wing.

As both forces collided, the Varangians held the line. When the Norman soldiers began to flee, they launched a brutal counterattack to chase them down.

In their pursuit, they became separated from the rest of the Byzantine forces, having followed the faltering Normans all the way to the sea. They became encircled by Robert’s soldiers and, exhausted and outnumbered, what was left of Alexius’s elite mercenaries fell back to a nearby church and barricaded themselves within.

Intent on obliterating them, the Normans set fire to the building and killed the remaining men trapped inside.

Having removed his rivals’ most dangerous weapon, Robert rallied his knights and soldiers and prepared them for a final charge into the Byzantine ranks. The result was crushing. The experienced Norman cavalry broke through, causing many of Alexius’s lackluster levies to rout or simply abandon the battle.

Faced with complete destruction, the Emperor was forced to flee as his army crumbled around him. As he retreated, he was struck by a lance to the chest, but his armor saved his life.

In 1082 CE, Dyyrachium fell. Robert continued his conquests into Greece, adding Macedonia and Thessaly to his domains.

But while the battle was an outstanding victory for the Normans, Robert’s excursion into Eastern Roman territory was already being taken advantage of by the Holy Roman Empire. Under Emperor Henry IV, they had invaded Italy and placed Rome under siege.

Robert, still committed to the papacy, was compelled to return to Italy. He left his son, Bohemond, to defend what he had taken, but the defeated Emperor Alexius I began a determined campaign to reclaim what he had lost.

In an attempt to retain his conquests, Robert would launch one last offensive against the Byzantines, but it would take his life. On the island of Kefalonia in 1085 CE, he would succumb to a fever that had spread throughout his camp.

Eventually, the Normans would be driven out of Greece and Illyria and forced back to their burgeoning homes in Italy and Sicily.

However, the Norman legacy was far from over. Under the reign of Robert’s nephew, Roger II, the flourishing Kingdom of Sicily would become a hub of trade, art, and culture.

Norman aptitude for statesmanship and law made their nations successful, and their rule would continue until the 13th century when they would finally lose power to the Hohenstaufen dynasty of the Holy Roman Empire.

They would also be at the forefront of the First Crusade at the end of the 11th century, establishing yet another kingdom at Antioch in the Middle East. Again, it was members of the expanding Hauteville family that would lead the charge into the holy land.

For a century, the Normans bent the world to their will. Their ambitions were unbridled as they traveled to distant lands.

Read another story from us: The Battle of Hastings: The Last Successful Invasion of England

When they began to assimilate into the populations of their new kingdoms, the identity of the Normans began to give way to the characteristics of the nations they had formed. But the results of their actions continue to echo throughout history, and the legacy they imparted upon the world can never be ignored or forgotten.

Within the span of a hundred years, the Normans’ uncontainable ambitions determined the course of Western civilization for ages to come.