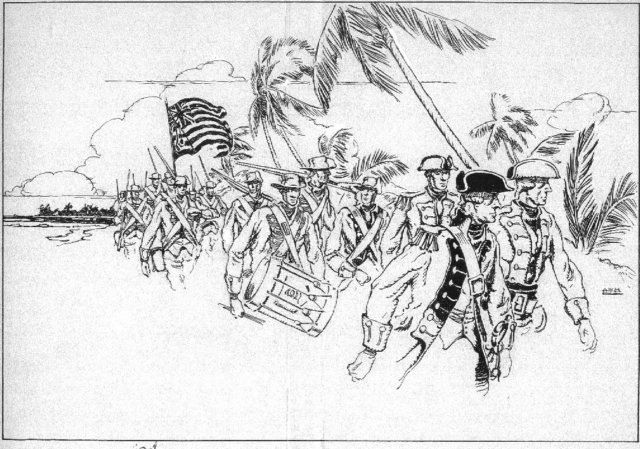

The Battle of Nassau was a naval operation and amphibious assault by the newly formed Continental Navy and Marines. It was the latter’s first amphibious landing and allowed the rebels to stock up on much-needed weapons and munitions.

Creation of the Continental Navy and Marines

On October 13, 1775, the Second Continental Congress created the Continental Navy. To build the fleet, it procured merchant and auxiliary vessels, which were then converted into warships. On November 5, Capt. Samuel Nicholas was appointed to lead a new section of the naval forces, the Continental Marines, whom he filled with men he met at Philadelphia’s Turn Tavern.

Around this time, the Continental Army was experiencing a shortage of gunpowder and munitions. This was due to actions taken by John Murray, 4th Earl of Dunmore, the British provincial governor of Virginia; at the outbreak of war, he had sent the colony’s stores to the island of New Providence in the Bahamas.

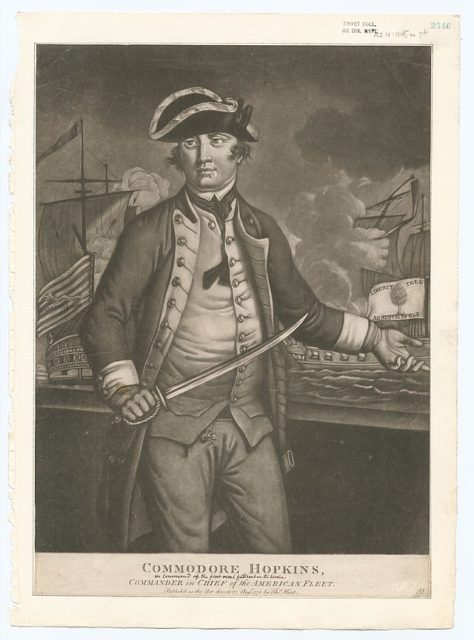

The shortage resulted in the Continental Congress organizing a naval expedition, with Commodore Esek Hopkins at the helm. He was given instructions to patrol the Chesapeake Bay and North Carolina coast and raid British ships. However, it’s believed he was secretly given additional orders to pursue operations that would be “most beneficial to the American cause” and best “distress the Enemy.”

To Hopkins, this meant staging an invasion in the Bahamas to steal the hidden munitions.

Sailing to the Bahamas

On January 4, 1776, Hopkins’ squadron, made up of the Alfred, USS Fly, Andrew Doria, USS Providence (1775), USS Columbus (1774) and USS Cabot (1775), began its journey down the Delaware River. Following a six-week delay near Reedy Island, caused by icy conditions, the expedition hit the Atlantic in the company of two other ships, the USS Wasp (1775) and Hornet (1775).

The fleet departed from Cape Henlopen, Delaware, on February 17. They experienced fierce gale-force winds while off the Virginia Capes, leading to a collision between Fly and Hornet. As a result, they became separated from the squadron, with the latter vessel returning to port for repairs. Fly would eventually return to the expedition, catching up with the fleet at Nassau.

Meanwhile, in the Bahamas, Gov. Montfort Browne received word of the expedition, his second warning of such an attempt. In August 1775, he’d been warned by Loyalist Gen. Thomas Gage that rebel soldiers may try to seize the supplies. Despite this, not one attempt was made to prepare an adequate defense.

Browne’s inaction was questionable, given the lack of defenses on Nassau. It had two forts along its coast, Nassau and Montagu, but both were ill-equipped to defend the island. Fort Nassau’s walls weren’t near strong enough to support its cannons during an amphibious attack, while Fort Montagu had little gunpowder on site.

‘Land the landing force’

The fleet arrived at Hole-In-The-Wall, at the south end of Abaco Island, on March 1, 1776. Along the way, they’d captured two Loyalist-owned sloops and forced their owners and crew into service. However, they hadn’t made it unnoticed; a local captain named George Dorsett had alerted Montfort Browne of their arrival.

The plan was to sail to Nassau during the early hours of March 3. The landing force was transferred to the two sloops and the USS Providence, but they were spotted. Browne, alerted to their impending arrival, ordered four guns be fired from Fort Montagu. The mission was subsequently aborted.

After rejoining the other ships at Hanover Sound, a new plan was devised for the fleet to land southeast of Fort Montagu. Between 12:00 PM and 2:00 PM, the Marines arrived to a truce flag – the lieutenant on Nassau realized he was sorely outnumbered against the invading force.

In the meantime, Browne arrived and ordered the fort’s guns fired before retreating the majority of his troops. This gave Samuel Nicholas cause for concern, but it didn’t stop his men from occupying the fort. He informed the lieutenant that the squadron was there to seize the gunpowder and weapons, and the news was brought to Browne’s attention.

Occupation of Nassau

Instead of further invading Nassau, Samuel Nicholas and his force of 50 sailors and over 200 Marines remained at the fort. This would prove a mistake, as, in the middle of the night, Montfort Browne had more than three-quarters of the island’s gunpowder loaded onto two ships, the Mississippi Packet and HMS St John, and sent to St. Augustine, Florida.

The next morning, March 4, 1776, Nicholas’ team entered Nassau without resistance, thanks to a leaflet that had been circulated. Written by Esek Hopkins, it outlined the reason behind the fleet’s landing and promised the safety of people and their property if there was no resistance.

Over the next two weeks, members of the fleet loaded as much weaponry as could fit onto their ships, including the remaining stock of gunpowder. They also obtained a third sloop to help carry the load.

Battle of Block Island

On March 17, 1776, the fleet left Nassau and began making its way to the Block Island Channel, off Newport, Rhode Island. The majority of the trip proved uneventful until April 4-6, when Esek Hopkins’ squadron captured the HMS Hawk and Bolton, the latter of which was filled with additional armaments and gunpowder.

Prisoners from the captured ships informed Hopkins that the British had established a large naval blockade just off the coast of Newport. Upon hearing this, he decided to change course and sail west to New London, Connecticut. However, it would appear his efforts were too late.

During the early hours of April 6, Capt. Tyringham Howe of the HMS Glasgow (1757) spotted Hopkins’ fleet, mistaking it for merchantmen. Action between the two began and, despite being sorely outnumbered, Glasgow was able to retreat while also causing significant damage to the USS Cabot and Alfred.

Return to America

Esek Hopkins and his men arrived in the harbor at New London on April 8, 1776. While they were initially celebrated for their efforts, the praise would be short-lived after complaints surfaced regarding their inability to capture the HMS Glasgow. There were also issues with the behavior of some of the fleet’s captains.

More from us: Did You Know Wartime Rationing Actually Helped the British Public Get Healthy?

Are you a fan of all things ships and submarines? If so, subscribe to our Daily Warships newsletter!

Hopkins was reprimanded for his failure to follow the orders set out to him regarding the patrol of the Virginia coast, and he was criticized for the way in which he distributed the spoils from the journey. In 1778, after several more missteps, he was forced out of the Continental Navy.