Some people lead such incredible lives; they are almost unbelievable. This lady was definitely one of them.

Marie Félicie Elisabeth Marvingt was born on February 20, 1875, in Aurillac, France. She was a Pisces – meaning she was destined to be perceptive, emotional, dreamy, mystical, and artistic. Her father was a postmaster who encouraged her to get into sports – not realizing just how far she would go.

The family later moved to the town of Metz (then in Germany), located at the confluence of the Moselle and Seille rivers. At age five, she swam 2.5 miles a day. Water polo, boxing, fencing, ju-jitsu, golf, hockey, horse riding, mountaineering, shooting, soccer, and tennis; she enjoyed them all.

Her mother died in 1889 when Marvingt was just 14. The family moved to Nancy where the hyper-athlete lived for the rest of her life. While caring for her father and brother, she added new hobbies to her repertoire – including cooking, singing, dancing, drawing, painting, and sculpture.

She also added more obscure disciplines like astrology, palmistry, and hypnotism, as well as circus skills such as rope balancing and juggling. Besides adding English to her native French and German, she also mastered Esperanto and learned to play the horn.

At 15, she canoed almost 250-miles from Nancy to Koblenz, Germany, and got herself a driver’s license in 1899. She obtained over twenty, first-prize awards for competitions in cooking, singing, fencing, shooting, ski jumping, etc. Marvingt also conquered almost every French and Swiss mountain from 1903 to 1910.

An adrenaline junky, she swam the length of the Seine through Paris in 1905. She became the first woman to win the First Gunner Palms sharpshooting award by the French Minister of War in 1907. So she was furious when she was banned from the Tour de France in 1908. Of the 114 men who joined, only 36 finished the course.

In retaliation, Marvingt cycled the same course when it was over and finished it. She was prepared as she had cycled to Naples in Italy two years before to watch Vesuvius explode. Impressed, the French Academy of Sports gave her the Gold Medal for “all sports” – the only one they ever gave out.

By then, however, Marvingt had found a new love – flying. She had gone up in a balloon in 1901 and piloted one on July 19, 1907. On October 26, 1909, she became the first woman to balloon across the North Sea to England. Shortly after, she began winning ballooning prizes, so planes were next.

Although she was the first woman to fly solo in a monoplane in 1910, she was the second one to earn a pilot’s license on November 8. Aerial competitions followed, but Marvingt had a new focus – planes as ambulances. She raised money for two, but the company responsible went bankrupt in 1912, so she tried again when WWI struck.

Knowing she would never be allowed to fight, but desperate to do so, Marvingt disguised herself as a man. Due to her athleticism, endurance, and sharp-shooting skills, she became a Soldier, 2nd Class in the 42nd Battalion of Foot Soldiers and went off to give the Germans hell.

She succeeded until it was discovered she was not a man. After getting kicked out, she made her way to Italy where they were not as squeamish about women fighting. Though not made a soldier, she was allowed to join the 3rd Regiment of Alpine Troops and fight in the Italian Dolomites.

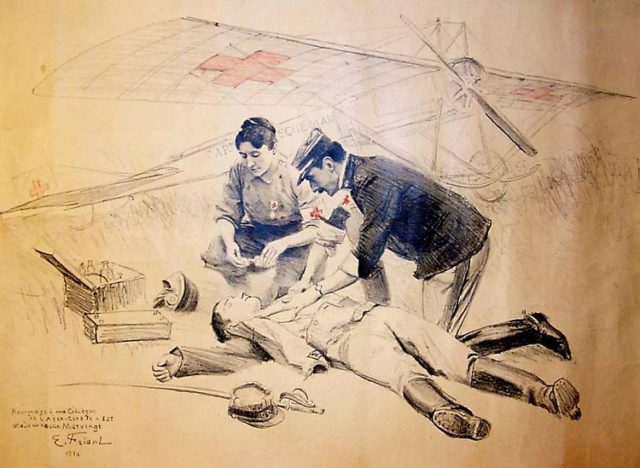

In 1915, the French government gave her permission to fly bombing missions over Germany – and a good thing, too. She destroyed a military base in Metz, earning herself a Croix de Guerre. Marvingt also acquired medical skills and helped the Red Cross as a nurse.

After WWI she worked as a journalist and nurse for the French Forces in North Africa when she had an epiphany – why not put metal skis on planes? She designed a set that allowed planes to land on sand, but it impressed no one – although they later worked on snow. Thereafter, she devoted herself to aerial medical evacuation.

Marvingt spent the rest of her life giving over 3,000 lectures on four continents on the subject. She co-founded Les Amies De L’Aviation Sanitaire (Friends of Medical Aviation – a medevac organization) and organized the First International Congress on Medical Aviation in 1929. She was a registered nurse by then.

To get things going, she set up the Challenge Capitaine-Écheman (Captain Écheman Challenge) in 1931 for the best plane that could be used as an ambulance. She got one in Morocco in 1934 – earning herself the Medal of Peace of Morocco. It inspired her to create the Nurses of the Air training courses for women.

Hardly surprising, then, that she became the first Certified Flight Nurse in 1935. For her work, the French government awarded her the Knight of the Legion of Honor on January 24, 1935. With war looming on the horizon, Marvingt created the Flying Ambulance Corps – an all-women staff of doctors, nurses, parachutists, and pilots.

Her next contribution was a new type of surgical suture. It allowed open wounds to be quickly and easily closed to reduce infection on the battlefield. She thought conventional procedures were inefficient and slow.

For her work in aviation medicine, the French National Federation of Aeronautics awarded her the Deutsch de la Meurthe grand prize on January 30, 1955. The US Air Force even gave her a present on her 80th birthday by giving her a ride in a jet fighter.

Fascinated, but unable to fly a jet fighter, she settled on learning to fly a helicopter, instead. Shortly after turning 86, she cycled 176 miles to Paris, just because she could. Sadly, she never got her helicopter pilot’s license because she died in 1963.