When the Kingdom of Parthia under its King Vologases IV began rattling its saber, the co-emperors had no choice but to march east to war.

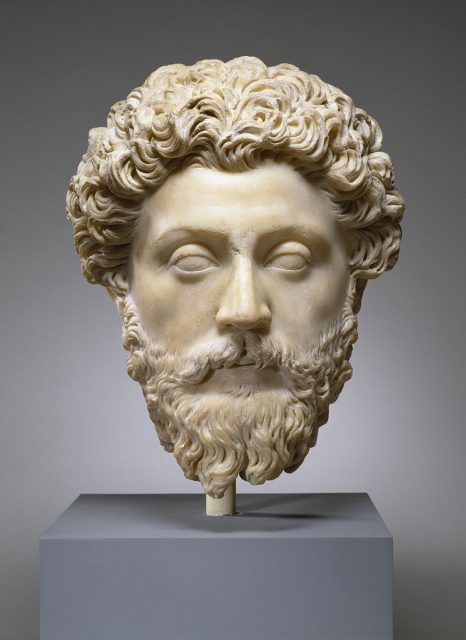

Marcus Aurelius’s reign signified both the pinnacle of the Roman Empire and the beginning of its decline.

As Edward Gibbon, the celebrated eighteenth-century British historian and Member of Parliament, put it in his book, The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, Marcus Aurelius was the last of the Five Good Emperors of Rome.

What makes Marcus Aurelius so special?

Statesmen like Bill Clinton and Wen Jiabao as well as investor Warren Buffet praise some of Marcus Aurelius’s gems of wisdom and virtue.

The peace-loving Roman Emperor, one of stoicism’s most illustrious proponents, spent the last ten years of his life writing what we now call his Mediations. These were private notes to himself, ideas on Stoic philosophy, and details on how to become a more virtuous human being.

“The only wealth, which you will keep forever, is the wealth you have given away” is one of Aurelius’s tenets. It sounds very much like something Warren Buffet read up on when he made his 37 billion dollar pledge to the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation.

Not only were Marcus Aurelius’s views and doctrines in his Mediations far before their time, but he also displayed unbiased fairness in the running of the Empire. He was one of the few Roman rulers who did not abuse his almost absolute power. Instead, he referred matters to the Senate for advice and permission such as, for example, on expenditure.

During a period riddled with war and pestilence, Marcus Aurelius devoted his life to a role he never wanted.

Marcus Aurelius loved peace but was almost constantly at war

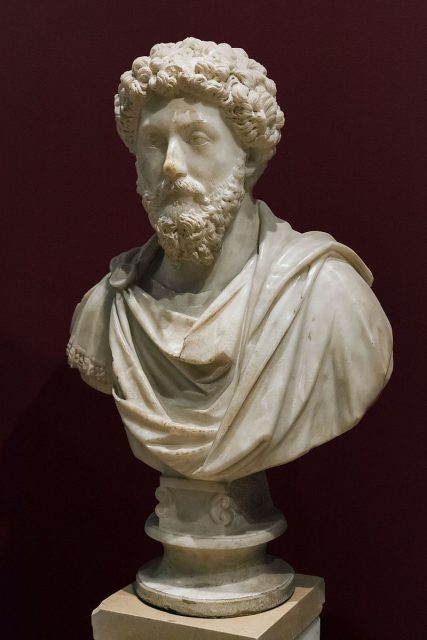

Marcus Aurelius was not a typical Roman Emperor. He did not enjoy travel, and he never spent time with the legions like most Roman rulers. He had spent most of his life in Italy before being given the purple robes of his high office.

https://youtu.be/eN1IML5g34I

Yet despite valuing peace and self-improvement, Marcus Aurelius was almost constantly at war. Why was this so?

First of all, times were different. It is one of the biggest mistakes when trying to make sense of history and the actions of the principal actors to superimpose present-day morals and ideals. We think differently today compared to a man who lived about 1,800 years ago. That can still be the case even with Marcus Aurelius who was far ahead of his time.

“Accept whatever comes to you woven in the pattern of your destiny, for what could more aptly fit your needs?” This is from the Meditations of Marcus Aurelius, and that is exactly what he did.

Marcus Aurelius Antoninus Augustus (his full name upon becoming emperor on March 7, 161), ruled the Roman Empire during one of its most tumultuous periods. The Antoine Plague ravaged the land throughout most of his reign from 165 to 180, killing some five million people throughout the Empire. Furthermore, the Empire was continuously at war.

Marcus Aurelius never wanted to become emperor, preferring to devote his life to his philosophical studies. However, his adopted father, the previous Emperor Antoninus Pius, had groomed him for the post in almost everything from administration to the law — but not in the art of war.

Aurelius’s lack of martial training and travel was probably due to the fact that his predecessor had enjoyed a period of almost uninterrupted peace and had ruled Rome effectively without needing to leave Italy.

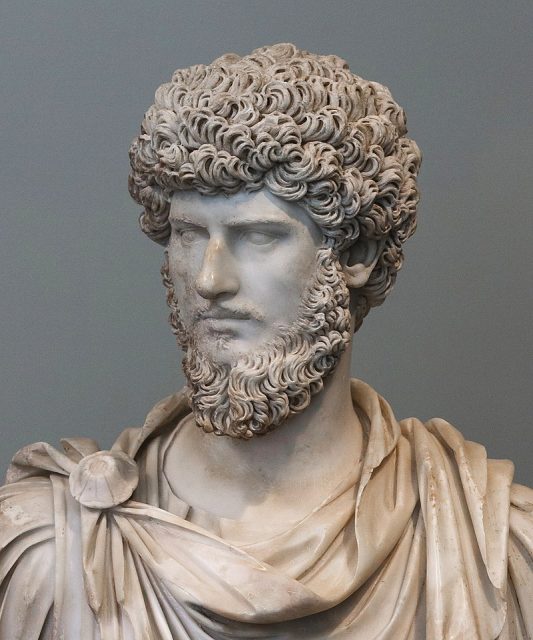

The moment Marcus Aurelius came to power, he promptly advised the Senate that he would rule alongside his adoptive brother Lucius Aurelius Verus Augustus. This is another sign of Marcus Aurelius’s honor, farsightedness, statesmanship, and efficiency.

First, by naming his stepbrother as co-ruler, he had acquiesced to the powerful Ceionius clan (Verus’s family prior to his adoption). Secondly, he wisely predicted many years of war for Rome if its ruler was to be absent from the capital for many years; two rulers solved that problem.

Despite his farsightedness, the war still came as a shock to the newly anointed Emperor Marcus Aurelius. The Roman Empire had enjoyed almost 40 years of mostly uninterrupted peace. Emperor Hadrian had pursued a policy of solidifying Rome’s frontiers and his successor, Antoninus Pius, had continued in the same manner.

So, when the Kingdom of Parthia under its King Vologases IV began rattling its saber, the co-emperors had no choice but to march east to war.

Marcus Aurelius was the more senior of the two rulers, and he sent Verus (the more physically fit of the pair) to fight Parthia.

Verus, with Aurelius’s blessing, took the cream of the Roman army with him. That in itself was an incredible act of trust on Aurelius’s part and another display of the man’s supreme integrity. In the past, many a general had taken advantage of such “Imperium” command over Rome’s forces and used it to claim the throne.

But Verus was more interested in the seductions of the Orient and his lionization there. At Corinth and Ephesus, Verus had been idolized as if he had already beaten Parthia. His bacchanalian procession continued via the fleshpots of Pamphylia and Cilicia.

Yet despite such laxity, the Romans ultimately prevailed against the Parthians. The war ended in 166, more down to the Empire’s able commanders than the debauched co-emperor.

Victory in the East was not the end of war for Marcus Aurelius

The long-feared Roman frontier with Germania (across the Rhine and Danube in present-day Germany, Austria, and parts of the Czech Republic) was a tinderbox ready to explode.

The Northern Germanic tribes — the Chatti and Chauci — had already launched pincer assaults into Gaul during the war with Parthia. Then, the Langobardi and Lacringi attacked Pannonia, a Roman province to the east of Italy, and were repulsed.

This Germanic saber rattling was only a harbinger of things to come. It was the beginning of a continuous conflict that would keep Marcus Aurelius busy for the rest of his reign.

In the year 168, Verus and Aurelius launched a campaign into Pannonia with two newly raised legions. Their presence was enough to convince the Germanic tribes of the Marcomanni and Victuali to back down and promise good conduct.

However, upon their return to Aquileia (located at the head of the Adriatic), Lucius Verus died. Some historians say his death was due to the plague. From that point onwards, Marcus Aurelius was the sole ruler of the Roman Empire, and his troubles were only just beginning.

Ballomar, the leader of the Marcomanni, formed an alliance with other Germanic tribes and invaded Italy proper. Ballomar’s Germanic coalition defeated the Romans at the Battle of Carnutum, overcoming 20,000 Roman legionaries.

The Marcomanni and their allies ultimately reached Aquileia, the place from which Aurelius and Verus had previously launched their attack.

From 170 to 180, the First Marcomannic War morphed into the Second. In the meantime, Marcus Aurelius also had to deal with a revolt led by Avidius Cassius, the Roman Prefect of Egypt.

The revolt occurred in the Eastern provinces and was sparked because of false rumors concerning the emperor’s death. This conflict put a hold on Marcus Aurelius’s plans to create two Roman provinces in Germania.

Marcus Aurelius eventually died in early autumn 180 on the cusp of a victory that might have enlarged the Empire right into the heartland of Greater Germania — something Aurelius never wanted in the first place.

His son and heir, Commodus, known for claiming to be the reincarnation of Hercules, immediately sued for peace with the Germanic tribes against the advice of his generals.

Read another story from us: Centurions and Cohorts: X Facts about the Roman Army

Despite his aversion to war, Marcus Aurelius pursued his unswerving duty to Rome. In some respects, his somewhat fictional depiction in the movie Gladiator correctly shows the moral standing and righteousness that marked him as one of Rome’s greatest leaders.

He waged war to protect Rome and what he believed in — not once did he pursue conquest for his own gain.