Limiting the effects of a nuclear attack can be a tough task, one that many nations took on (mostly in vain) during the Cold War. An entire generation was raised in the era of “duck and cover” drills and educated on what to do to survive a nuclear blast. However, this was only the tip of the iceberg when it came to America’s plans to survive such an attack.

The creation of hydrogen bombs

The idea of nuclear attack in relatively new, with humanity only gaining control over these types of weapons in the 1940s. They have been used in anger on two occasions: both by the US on Japanese cities, swiftly bringing World War II to a close. Back then, the US was the world’s first and only nuclear power – a powerful position and one they thought they’d keep for a long time.

The leader of the Manhattan Project estimated the Soviet Union was two decades away from developing an atomic bomb. That might have been true, had it not been for Soviet spies.

On August 29, 1949, the Soviets shocked the world by detonating their first atomic weapon, RDS-1. With this, the US became vulnerable to the very weapon its scientists created.

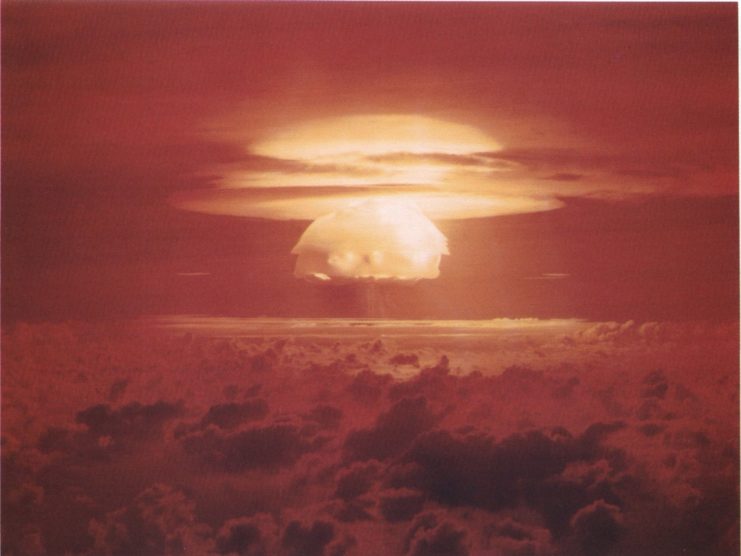

This was made even worse by both nations’ development of hydrogen bombs. In March 1954, the US conducted the Castle Bravo nuclear test. The bomb had a yield of 15 megatons (15 million tons of TNT) and nearly killed the entire test team. Although not intended to be as powerful as it was, the results highlighted the true capabilities of such bombs.

The USSR detonated its first two-stage hydrogen bomb the following year.

Following Castle Bravo’s fearsome display, US President Dwight D. Eisenhower was shown its power in a more understandable way: by placing the blast zone atop a map of Washington, D.C. Unsurprisingly, it wasn’t a pretty sight.

If Washington had been the blast location, every resident in the Washington-Baltimore area would have been killed, and those not immediately vaporized by the blast would have died minutes later due to radiation exposure. Philadelphia would have lost most of its residents within the hour due to radiation, while half of New York City‘s population would have perished by sunset.

When you consider that this blast wasn’t even remotely near the power limits of nuclear weapons, it’s not surprising the American government was terrified. If the country went to war with the USSR, the plan was to use nuclear weapons on Soviet troops stationed in Europe to even the odds against their numerical advantages. This was based on the belief that they couldn’t inflict too much retaliatory damage on the US mainland.

However, with the advent of these much more powerful bombs, unimaginable destruction could be brought against America. As such, Eisenhower and his administration needed a new strategy.

Civil defense: realistic or false hope?

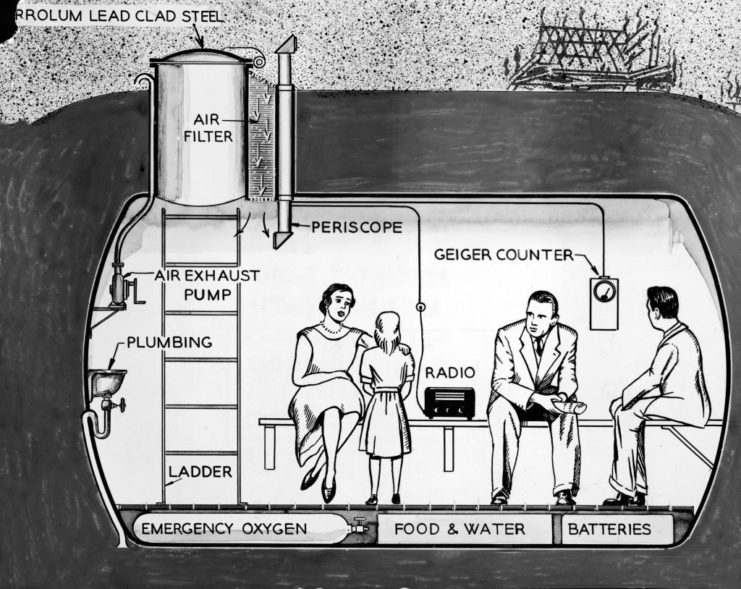

One of the main ideas the US had to minimize damage was civil defense. Throughout the Cold War, there was much back and forth regarding what the ideal civil defense plan was, with no conclusion ever reached. Budget constraints and disagreements limited success, but some plans were put in place nonetheless.

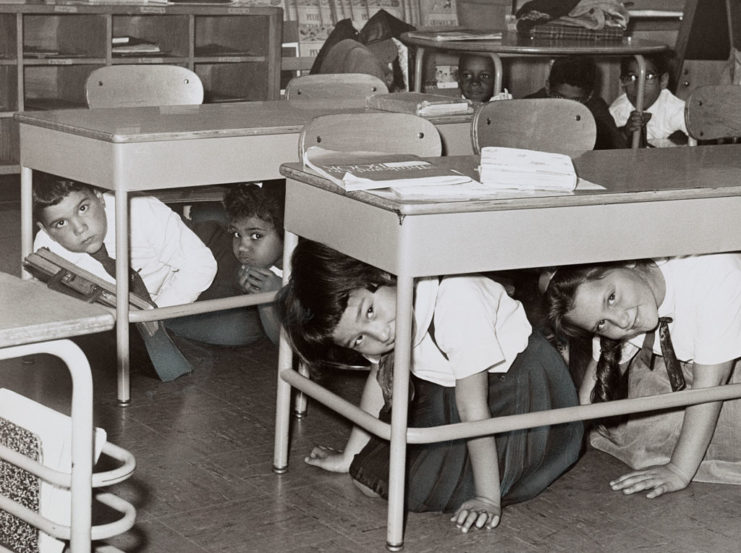

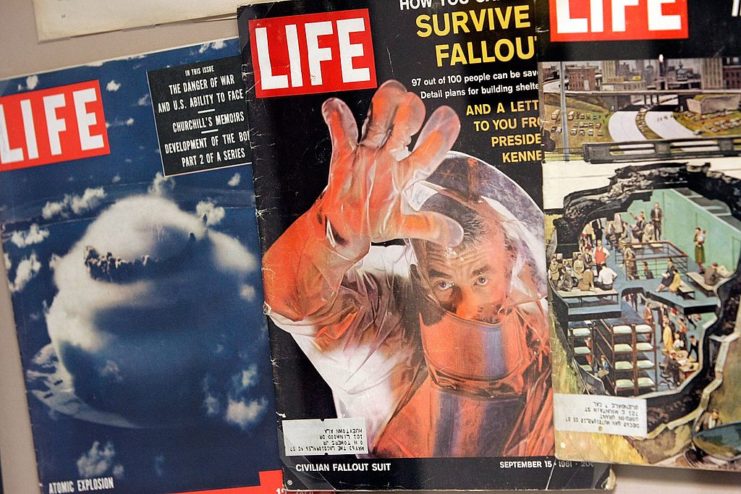

Educating the public was one of the key points. If each American knew what to do in the event of a nuclear attack, millions of lives could be saved. This led to the classic “duck and cover” drills taught to children in schools. Cartoons were used to demonstrate what to do, without being overbearingly heavy. People were also advised to assemble an emergency supply of first aid, food and water.

A program called “Alert America” saw a convoy of semi-trucks travel 36,000 miles around the US, visiting cities and educating the public on how best to prepare for – and survive – a nuclear attack. The civil defense plans also caved out strong gender roles. Women were taught how to manage the home and kitchen during peacetime, so they could take care of nursing and kitchen work in shelters following an attack.

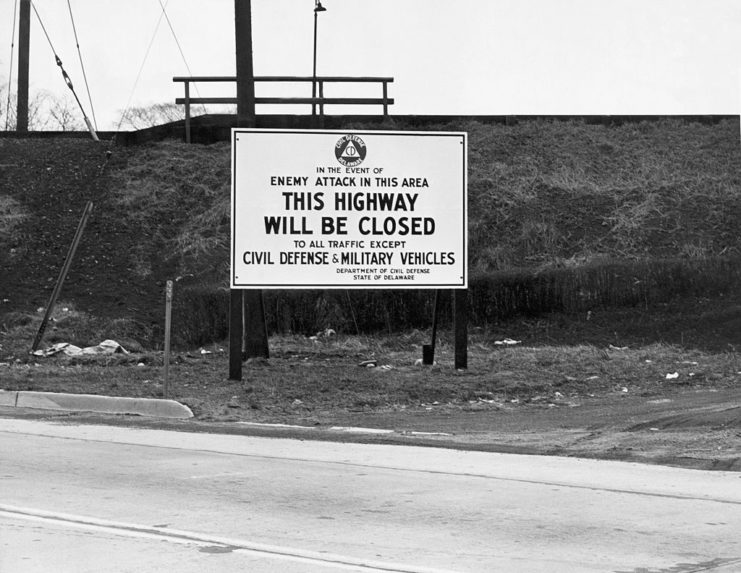

Initially, there was resistance within the government to evacuate cities before an attack, but it was later decided it was better than keeping the population where they were. Trucks would take hospital patients out of a city, while those in cars were to fill their vehicles with passengers and flee. Heavy construction equipment and machinery was to be taken to designated areas.

This was to be completed within the span of 20 minutes, depending on the size of the city. At this point in the Cold War, nuclear weapons were delivered by slow-moving bombers, making it a realistic target. However, intercontinental ballistic missiles soon made this virtually impossible.

While many were aware that these plans would likely be of little help, Eisenhower’s administration tried to make them seem plausible to the general public.

Skeptical about the likelihood of surviving a nuclear attack

In the mid-1950s, the government held Operation Alert, a nationwide practice run of a real nuclear attack. While intended to show how prepared the country was, reports stated they “clearly exposed the nation’s un-readiness to cope with a thermonuclear attack.” It was known the American public had little confidence of surviving such events, a sentiment that was further made clear by investigations conducted by Chet Holifield in 1956.

One of the government’s plans was to dig trenches along the highways leading out of all major US cities. In the event of a nuclear attack, people were to immediately flee, and if the bombs hit while they were on the road, they were to stop driving, exit their vehicles, drop down into the trenches and cover themselves with dirt.

Further discussions revealed the government hadn’t planned much past surviving the initial blast, as those in the trenches would have no access to food or water. After this came to light, politician Frederick “Val” Peterson stated the entire country would likely suffer, saying, “I think the best we will be able to do in the United States is to run soup kitchens.”

Fortunately, these systems were never tested, but it is likely there was little the government – nor anyone else – could do to stop large portions of the population being killed. These were weapons that utilized the universe’s fundamental forces, after all.

Some good did come from Eisenhower’s efforts. Evacuation plans contributed to the construction of the interstate highway system, while means of maintaining a government after an attack led to the creation of shelters all over the country. As well, the vulnerability of the US may have prevented the Cold War getting too hot, as the government knew how high the death toll would be in the event of an attack. As such, this may have helped push diplomatic solutions, rather than war.