For over a thousand years, Britain and France have had a tumultuous relationship. Ever since the Duke of Normandy, William the Conqueror, successfully invaded England in 1066 and claimed the English throne, the two nations have alternated between uneasy peace and war.

Yet despite these turbulent dynamics over ten centuries, they almost became a single nation, the Franco-British Union, during the Second World War. It was a motion that was backed by Churchill and the British Cabinet, as well as French Prime Minister Reynaud and Charles de Gaulle but ultimately blocked by the French Cabinet.

Before getting to the point at which it was suggested that Britain and France become one country, it’s important to examine some of the backstory behind the sometimes amicable, sometimes hostile, usually tense relationship between the two nations.

The proposal to unite the two nations during WW2 wasn’t the first time such a thing had come close to happening. However, when it had last been a possibility, both countries had been kingdoms. This was long before the concept of the nation-state had come into existence.

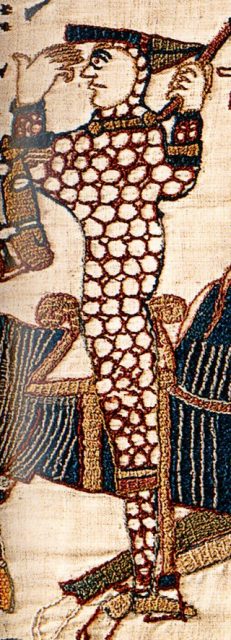

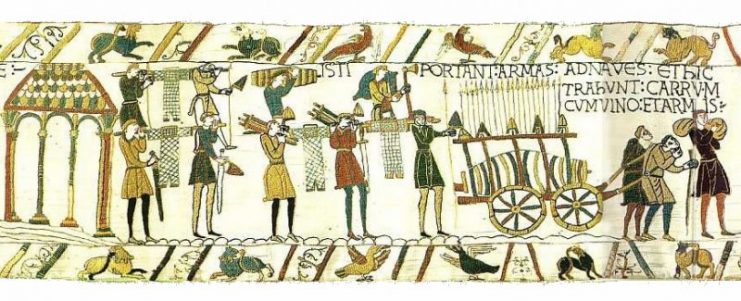

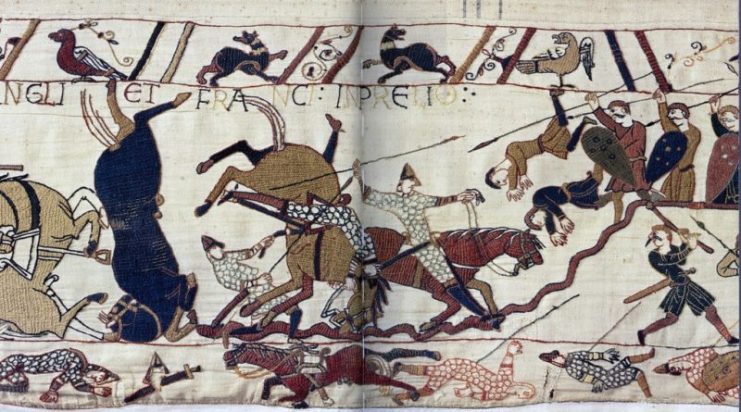

When William, Duke of Normandy, and his men invaded England in 1066 and defeated the Anglo-Saxons at the Battle of Hastings, he changed the course of history for both England and France.

The Norman conquerors changed the English language over the course of the next few centuries, to the point where around 45% of English words were derived from French.

However, despite this merging of language and culture, the French and the English remained two very separate nations. Over the next few centuries, the rulers of both France and England would continually battle over various territories and kingdoms — as well as each other’s thrones.

The Hundred Years War (which actually lasted 116 years) saw England and France in a period of prolonged conflict. Even after it ended in 1453, the peace between these two nations was brittle at best.

Both nations came to blows again in the New World, establishing rival colonies. They ended up fighting one another in a proxy war, as France backed the fledgling United States in their War of Independence against Britain.

Later, in the aftermath of the French Revolution, Napoleon Bonaparte and his armies set off to conquer Europe. Britain played a key role in putting an end to his – and France’s – ambitions.

After this long period of sustained animosity, however, relations between France and Britain began to improve. By the early 20th century, they were closer than ever before as they fought side by side as allies in the First World War.

Yet it was when Hitler’s Third Reich threatened the stability of the entire European continent in 1939 that Britain and France got to the point at which they seriously considered becoming a single, unified country.

The idea to unify the two countries was first proposed by the head of the Anglo-French Coordinating Committee, Jean Monnet, in December 1939. Monnet was an ambitious visionary whose ultimate goal was a United States of Europe modeled on the United States of America.

He discussed his idea to join France and Britain as one country – which would be called the Franco-British Union – with Neville Chamberlain and Winston Churchill, along with other prominent British political figures. All were in favor of it.

When the Nazi invasion of France and the Low Countries began on the 10th of May 1940, Prime Minister Reynaud’s position became tenuous. After it became clear that the German forces could not be resisted, much of his cabinet wanted him to agree the terms of an armistice with Germany.

Britain, however, did not want France to agree to any separate armistice terms. Charles de Gaulle, a staunch supporter of Reynaud and a man who refused to capitulate to the Germans, talked with Monnet about his unification idea. He urged Churchill and his cabinet to push for it.

If France and Britain could be officially unified, France could bolster its fight against the German invaders.

Churchill and his War Cabinet agreed that it was a sound idea. Under the terms proposed, the Franco-British Union would have been a single nation with one unified military and a single currency. All British nationals and French nationals would automatically become citizens of the Union. They would able to move freely throughout its territory, which would include all of Great Britain and all of France.

Prime Minister Reynaud was eager to go forward with this plan, chiefly because it meant that he could continue the fight against the German invaders instead of having to surrender.

But while some members of his cabinet backed him, many were far less enthusiastic about the prospect of uniting their country with Britain. Indeed, some went as far as saying they would rather be a province of the Nazi Reich than unify with Britain.

Read another story from us: How France Fell to the Nazi Invaders

Reynaud, disappointed in the lack of support from his cabinet, resigned shortly after presenting the idea. A new government was formed by Philippe Pétain, a former general of WW1 and a supporter of seeking peace with Germany.

Under Pétain, the Armistice of the 22nd of June 1940 was signed between France and Germany – and that was the final nail in the coffin for any unification plans between France and Britain.